The Formation of the Biblical Canon

by Fred Zaspel

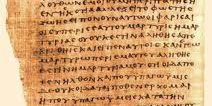

The books of our Old Testament became recognized as “canon” in the same way that the Old Testament itself was formed — gradually, as holy men of old spoke and wrote, being moved of the Holy Spirit. In various ways and at various times throughout the old covenant times God spoke to his people through the prophets, and as they delivered God’s word to the people, whether in oral or written form, it was recognized as of divine origin and, hence, “canon” authority. Gradually these canonical books were collected and gathered together and became known among the Jews as The Law, the Prophets, and the Writings, or, briefer, The Law and the Prophets, or in briefest shorthand, The Law. This that we now call The Old Testament was the “Bible” of Christ (cf. Luke 24:44). We have it on Christ’s authority that these books of the Old Testament are to be considered canonical, fully authoritative. It is no surprise, therefore, to find that the Old Covenant Scriptures continued in use as the Bible of the early church (cf. Acts 13:15).

It would be a mistake, however, to assume that the Bible of the early church consisted only of these books. Beginning immediately in the apostolic age these new spokesmen for our Lord began to enjoin on the church additional writings which were to be held — and which were held by the apostles themselves — in equal regard. Gradually and one by one writings came from the apostles’ pens and were imposed on the church and received by the church as canon (e.g., 1Cor. 14:37; 1Thes. 2:13; 4:1-2; 2Thes. 2:15; 3:6, 14; 1Tim. 6:3; Rev. 1:11; 2:1, etc.). The apostles themselves as well as the churches to whom they wrote recognized their word as on par with that older revelation (1Tim. 5:18; 2Pet. 3:16), and as this new revelation came to them it was revered as from Christ.

Nor was this apostolic authority self-made. Christ had commissioned them to this task exactly, and this was to be the role they would serve in the history of the church. The Lord Jesus Christ had come from heaven as God’s climactic self-revelation (Heb.1:1-2), and he appointed these men as his personal legates, directing them to be his spokesmen. He had brought the revelation of God to them, and they, in turn, were to take this revelation to the world (John 17:6-8, 14, 18, 20). In order to equip them to fulfill this role successfully Christ sent them “another helper,” his replacement, the Holy Spirit of God who would teach them “all things” and “bring to their remembrance” all that Jesus himself had taught them (John 14:24-26). The Spirit of Christ was promised to speak for Christ and guide the apostles into “all truth” and reveal to them “things to come” (John 16:12-13). They would be the final repositories of God’s full and final revelation in Christ and thus became, in a sense, the “foundation” of the church (Eph. 2:20). Their written “witness” (John 21:24) to Christ was, in fact, Christ’s continued revelation to his church.

Significantly, these statements of our Lord not only point to the apostles and their role in the creation of the New Testament canon, but they constitute description of the New Testament itself given ahead of time. The Spirit will “remind” the apostles of what Jesus had done and said; this the apostles gave us in the Gospels. He will “lead them into all truth” and show them the fuller significance of what Jesus had said and done; this is what is proclaimed in the Acts and expounded in the Epistles. And he will “show them things to come”; we have this in the prophecies of the Epistles and in the book of Revelation. God’s word to us climaxed in his Son, and this word was reduced to writing in the pages of our New Testament.

So the New Testament canon grew in a way similar to that of the Old Testament, and as the revelation came it was recognized and accepted as such by the church and laid beside the older canon as equally authoritative. The books of the Old and New Testaments alike were to be read in the assemblies (cf. 1Thes. 5:27; Col. 4:16; Rev. 1:3).

The apostles themselves having placed their writings on par with the Old Testament (1Tim. 5:18; 2Pet. 3:16), the early church immediately followed suit. Polycarp in AD 115, for example, linked Psalms and Ephesians equally as “Scripture.” Clement likewise linked Isaiah and Matthew as “Scripture,” and so on.

Of course, in the day before moveable type, mass reproduction copies were slow in coming, and individual churches were slow in receiving the New Testament canon in full. As in the days before Christ, the New Testament church recognized a canon in progress. Just as Israel’s earlier canon grew over the centuries, so the church’s canon grew over the course of the second half of the first century, A.D. New book after new book was received from the apostolic company and welcomed as the rule of faith, laid beside the older revelation and together designated, The Law and the Prophets with the Gospels and the Apostles, or more briefly, The Law and the Gospel. The newer additions to the canon, The Gospels and the Apostles, or more briefly, The Gospel, was not viewed by the early church as different from the older canon but as additions to it. Of course the “canon” that was recognized by each assembly varied from locality to locality, as the copies were hand-made and then hand-delivered to successive churches. And as the various churches gradually became acquainted with new apostolic writings their canon gradually became complete. But from the time of Irenaeus (c. 175), the disciple of Polycarp, the church at large had the complete canon as we now possess it ourselves.

The criterion for recognition of this growing canon was, simply, apostolicity — apostolic endorsement. These men were the spokesmen for the Lord, and it was theirs to impose the new rule upon the church. Apostolicity does not necessarily imply apostolic authorship but apostolic endorsement — “imposition by the apostles,” as Warfield puts it. Thus Paul cites Luke as “scripture,” Hebrews is recognized as “Pauline” at least in some sense, and so on.

What is important to recognize in all this is that both the Old and New Testaments, coming to us before and after Christ respectively, are alike given to us from Christ. He gives his divine imprimatur on both — one after the fact and one before. It is therefore on his authority that the church recognizes its present Biblical canon.

Fred Zaspel holds a Ph.D. in historical theology from the Free University of Amsterdam. He is currently a pastor at the Reformed Baptist Church of Franconia, PA. He is also an Adjunct Professor of Systematic Theology at Calvary Baptist Seminary in Lansdale, PA. He is also the author of The Continuing Relevance of Divine Law (1991); The Theology of Fulfillment (1994); Jews, Gentiles, & the Goal of Redemptive History (1996); New Covenant Theology with Tom Wells (New Covenant Media); The Theology of B.B. Warfield: A Systematic Summary (Crossway, 2010). Fred is married to Kimberly and they have two children, Gina and Jim.