What is saving faith really? Jonathan Edwards’ departure from Reformed theology, Part 1

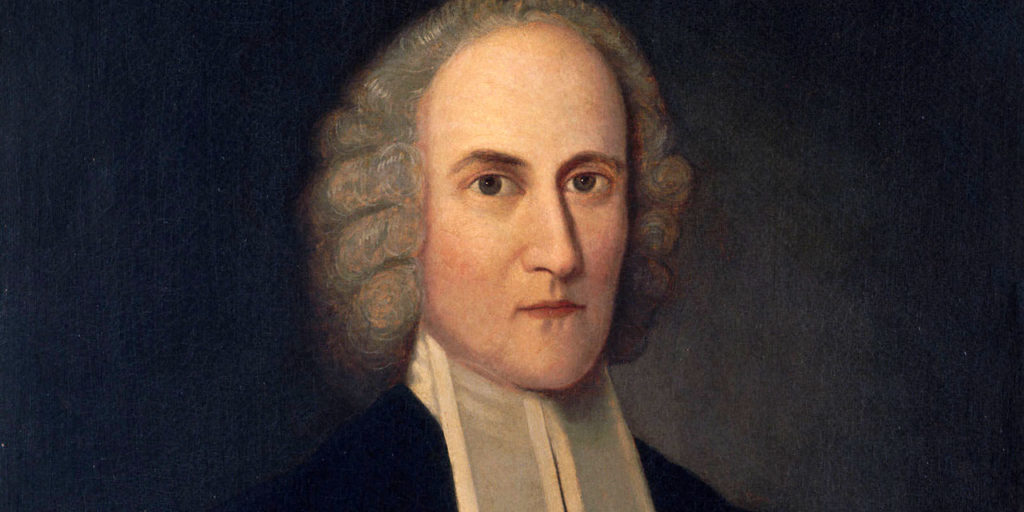

Without a doubt, Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758) was one of the most creative and prolific theologians America has ever produced. Interpreters of Edwards have sharply disagreed over how Edwards’s understanding of justification fits within the Reformed tradition. While Edwards generally sought to promote a Reformed understanding of justification, interpreters of Edwards are divided as to how clearly and how faithfully he establishes himself within this tradition overall.[1] Interpretive disagreements over Edwards’s doctrine of salvation are nothing new. On the matter of imputation, James W. Alexander of Princeton stated that “Edwards has never been regarded as an interpreter of our doctrines.”[2] This is perhaps why Charles Hodge in his Systematic Theology found it necessary to defend Edwards in this regard: “President Edwards, who is regarded as having initiated certain departures from some points of the Reformed faith, was firm in his adherence to this [the Reformed] view of justification.”[3] Many others from within the confessionally Reformed tradition have similarly defended Edwards as being faithful to the Reformed understanding of justification by faith alone.[4] Still others, both from within the Reformed tradition and without, have noted significant deviations in Edwards’s articulation of the doctrine from the traditional Reformed position.[5] All interpreters agree that Edwards uses expressions and categories of thought that are unique to his tradition. But are these peculiarities merely incidental differences pertaining to the “mode of expression”[6] or are the differences more substantial? This is the debate.

From the main outlines of Edwards’s work published specifically on justification, it is clear that Edwards generally expressed a Reformed understanding of justification by faith alone. Keeping in line with his own master’s thesis on justification,[7] Edwards’s Justification by Faith Alone contains this statement as its central doctrine: “We are justified by faith in Christ, and not by any manner of virtue or goodness of our own.”[8] Edwards’s subsequent defense of this statement contains the essential categories and expressions of a Reformed formulation: Christ as the second Adam and representative of his people,[9] the active and passive obedience of Christ,[10] union with Christ by faith,[11] and imputed righteousness as the sole ground of the sinner’s justification.[12] Within the overarching structure of Edwards’s presentation, which is undoubtedly Reformed and traditional, Edwards says many specific things, however, which have caused interpreters to question his consistency in carrying out the Reformed articulation. It is at the level of specific details, then, that we must give due attention.[13]

In comparing Edwards to representatives of the Reformed tradition, particularly John Calvin and Francis Turretin,[14] we will focus on the specific role of love, obedience, and perseverance as it relates to justifying faith. While Edwards was willing to align himself with the so-called “Solifidians”[15] of his day, we will call into question whether Edwards’s conception of faith in justification consistently upholds the Reformed tradition’s notion of sola fide.

The Role of Faith in Justification

Edwards is very clear that faith does not justify a believer as a virtue or as forming any part of the righteousness which is the basis or ground of God’s judicial verdict.[16] In this, he clearly stands with the Reformed tradition over against the Arminian divines he explicitly opposed. Edwards does, however, state the role of faith in justification somewhat uniquely from his tradition. The Reformed tradition had been content to often refer to faith as the “instrument” of justification.[17] Edwards, however, feels this is an “obscure way of speaking.”[18] Instead, Edwards conceives of faith as a “qualification” for justification. While the imputed righteousness of Christ forms the sole basis of an individual’s justification, “…faith in this Mediator is that which renders it a meet and suitable thing, in the sight of God, that the believer rather than others should have this purchased benefit assigned to him.”[19] Edwards goes on to describe faith as the “qualification wherein the meetness to this benefit consists.” How exactly does faith qualify a believer for justification? It does so, according to Edwards, “as it unites to that Mediator, in and by whom we are justified.”[20] Faith’s role in justification is that it unites the believer to Christ. It is not as though God rewards the goodness of faith by uniting the believer to Christ; rather, faith is “that in him, which, on his part, makes up this union between him and Christ.”[21] It is “the Christian’s uniting act.”[22]

Faith, for Edwards, is what forms a real union with Christ. This real, volitional uniting with Christ, in turn, is what qualifies the believer for a legal union with Christ, from which all of the justifying benefits of Christ flow to the believer. As in a marriage union, faith is the consensual act of receiving one’s spouse to oneself in union, which in turn forms the foundation for a declarative legal union. This active, volitional faith-union is what forms the basis, then, of the legal union between Christ and the believer. Says Edwards:

God sees fit, that in order to an [sic] union’s being established between two intelligent active beings or persons, so that they should be looked upon as one, there should be the mutual act of both, that each should receive the other, as actively joining themselves one to another. God in requiring this in order to an [sic] union with Christ as one of his people, treats men as reasonable creatures, capable of act, and choice; and hence sees it fit that they only, that are one with Christ by their own act, should be looked upon as one in law: what is real in the union between Christ and his people, is the foundation for what is legal; that is, it is something really in them, and between them, uniting them, that is the ground of the suitableness of their being accounted as one by the Judge.[23]

The role of faith, then, is to form a real union with Christ, which in turn is the foundation for the believer’s legal union with Christ. Out of this legal union, “it necessarily follows, or rather is implied” that God “accepts the satisfaction and merits of the one, for the other, is if it were their satisfaction and merits,” referring here to Christ’s vicarious atonement and the imputation of Christ’s righteousness.

Edwards breaks with the Reformed tradition over sola fide. Click To Tweet The question still remains for Edwards: what compels God to grant such a legal union to those who are so united to Christ by faith? Edwards denies that such a union is granted as a reward for faith or that faith possesses any sort of congruous merit. Instead, Edwards says that there is a “natural fitness” (as opposed to a “moral fitness”) between a believer’s volitional faith union with Christ and God’s granting of a legal union with Christ. It is out of a “love of order” that God bestows such a legal union, not out of a “love to the grace of faith itself.” Says Edwards: “God looks on it fit by a natural fitness, that he whose heart sincerely unites itself to Christ as his Savior, should be looked upon as united to that Savior, and so having an interest in him.” Edwards puts it all together like this: “[It is] because [God] is a wise being, and delights in order, and not in confusion, and that things should be together or asunder according to their nature; and his making such a constitution is a testimony of his love of order.”[24] We can sum up Edwards’s position as follows: Because faith actually unites a believer’s soul to Christ, and because a corresponding legal union with Christ is so derived (flowing out of God’s “love of order”), faith “qualifies” a believer for justification.

How different is this understanding of the role and function of justifying faith from his Reformed predecessors? Although Calvin and Turretin did not prefer the word “qualification” for faith, these representatives of the Reformed tradition seem to agree with Edwards in positing a real faith-union with Christ as the foundation for the imputation of Christ’s righteousness. Calvin’s writing on this matter bears remarkable similarities with Edwards’s essential conception of the role of faith in justification when he says:

…we are deprived of this utterly incomparable good [i.e. justification] until Christ is made ours. Therefore, that joining together of Head and members, that indwelling of Christ in our hearts—in short, that mystical union—are accorded by us the highest degree of importance, so that Christ, having been made ours, makes us sharers with him in the gifts with which he has been endowed. We do not, therefore, contemplated him outside ourselves from afar in order that his righteousness may be imputed to us but because we put on Christ and are engrafted into his body—in short—because he deigns to make us one with him. For this reason, we glory that we have fellowship of righteousness with him.[25]

A believer’s real union with Christ, for Calvin as well as for Edwards, logically precedes the imputation of righteousness. Turretin also expresses a similar notion when he says:

…faith is also sometimes described as…an act of adhesion and binding closely, and of the most strict union by which we are bone of his bone and flesh of his flesh and one with him; and Christ himself dwells in us (Eph. 3:17) and we in him (Jn. 15:5). From this union of persons arises the participation in the blessings of Christ, to which (by union with him) we acquire a right (to wit, justification, adoption, sanctification and glorification).[26]

Edwards blends love and faith together where Turretin had strenuously kept them apart. Click To Tweet Edwards’s similarities with Calvin and Turretin in this regard should be duly noted. In conceiving of a real union as logically preceding a legal union, Edwards does not appear to be outside of his Reformed tradition.[27] In any event, Edwards clearly distinguishes himself from an Arminian view of faith’s role in justification. Faith is no part of the ground of justification; rather, faith justifies only in that it brings about a legal union with Christ. Although he doesn’t prefer the word “instrument” and although he calls faith a “qualification” by “natural fitness” for union with Christ, on this point Edwards seems to fit generally within the mainstream of his Reformed tradition on the role of faith in justification: “Thus it is that faith justifies, or gives an interest in Christ’s satisfaction and merits, and a right to the benefits procured thereby, viz. as it thus makes Christ and the believer one in the acceptance of the Supreme Judge.”[28]

The Essence of Justifying Faith

In the material covered thus far, Edwards’s thinking on justifying faith seems to fall generally in line with the Reformed tradition. As we progress and look at the essence of justifying faith, however, we begin to see Edwards deviate from his tradition significantly. The Reformed tradition has traditionally spoken of faith as having three acts which make up its essence—namely, knowledge (notitia), assent (assensus), and trust (fiducia).[29] The Reformed tradition was clear that other Christian graces do not enter into the essence of faith; rather, all the other graces are said to flow from or grow out of faith. For Calvin, hope,[30] love,[31] and repentance[32] were all viewed as proceeding from faith and not forming part of its essence. They are the fruit of faith. Likewise, Turretin rejected the blending of love into faith which the Roman Catholics traditionally did in their understanding of justifying faith as “formed faith” (i.e. assent taking on the form and power of love into its essence). Turretin is representative of the Reformed tradition when he says:

[The] two virtues…are mutually distinct—‘faith and love’ (1 Cor. 13:13). The former is concerned with the promises of the gospel; the latter with the precepts of the law (which on this account is said to be the end of ‘fulfilling of the law,’ Rom. 13:10). The former is the cause, the latter the effect… [Faith] is the instrument of justification, while [love] is its consequent fruit.[33]

Given its interaction with Roman Catholics over their conception of “formed faith,” the Reformed tradition historically was careful to delineate saving faith along the lines of knowledge, assent, and trust, keeping it distinct from the other concomitant graces in the soul, especially love.

Edwards’s break with the Reformed tradition over sola fide begins to show itself as he relates faith to the other Christian graces. Seeing much more in faith than notitia, assensus, and fiducia, Edwards injects into faith many of the virtues of the Christian life. Edwards’s divergent views on this matter can be seen as early as his aforementioned Master’s thesis on justification by faith:

In this thesis we wish to argue that receiving Christ and his benefits takes place by faith of the entire soul; it is not merely the intellect’s reception by assent, not merely the will’s reception by choosing him, not only the affections’ reception in love, nor merely the capacities we have for action receiving him in obedience. Rather, it is the reception of the entire soul, which includes all of these.[34]

“Faith of the entire soul” for Edwards, then, includes graces like love and obedience, which his inherited Reformed tradition viewed as fruits of faith and not properly a part of faith. Edwards continued this line of thinking when he published his expanded sermon series, Justification by Faith Alone. In it he states that

faith includes the whole act of unition to Christ as Savior: the entire active uniting of the soul, or the whole of what is called ‘coming to’ Christ, and ‘receiving’ of him, is called faith in Scripture; and however other things may be no less excellent than faith, yet ‘tis not the nature of any other graces or virtues directly to close with Christ as a Mediator, any further than they enter into the constitution of justifying faith, and do belong to its nature.[35]

The last part of our quotation begs for elaboration, but in the immediate context, Edwards gives us none. Edwards does share with the Roman Catholic view that love is “the very life and soul” of justifying faith. Click To Tweet

One has to look to the opening sermon of Edwards’s Charity and Its Fruits, entitled “Love the Sum of All Virtue” to see how love enters “into the constitution of justifying faith” and belongs “to its nature.” The central doctrine of this sermon is as follows: “All that virtue which is saving, and distinguishing of true Christians from others, is summed up in Christian or divine love.”[36] Later in the sermon, he states: “Love is an ingredient in true and saving faith, and is what is most essential and distinguishing in it. …it is the life and soul of a practical faith”. Arguing in a way similar to Roman Catholics in their discussion of “formed” versus “unformed” faith, Edwards states that what makes saving faith different from the faith of devils is love: “the devils have faith so far as it can be without love.”[37] Whereas Turretin clearly distinguished between faith as called for under the gospel and love as called for under the law, Edwards blends love and faith together where Turretin had strenuously kept them apart. Says Edwards:

Faith is a duty required in the first table of the law, and in the first commandment; and there it will follow that it is comprehended in the great commandment, ‘Thou shall love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind’ [Matt. 22:37]. And so it will follow that love is the most essential thing in a true faith. …love is the very life and soul of a true faith…it is love that is this active working spirit which is in true faith. That is its very soul without which it is dead…[38]

In answering the Roman Catholic notion of “formed” versus “unformed” faith, Turretin had explicitly denied that faith is “made operative by love…as if it borrowed its universal efficacy from love.”[39] Yet this seems to be the very position of Edwards.[40] While no one would argue that Edwards held to an exactly Roman Catholic doctrine of “formed faith,” Edwards does share with the Roman Catholic view that love is “the very life and soul” of justifying faith. In this he is at divergence with the Reformed tradition.[41] Distinguishing between faith and love was necessary for Turretin and others to uphold the Protestant distinction between the law and the gospel.

Distinguishing between faith and love was necessary for Turretin and others to uphold the Protestant distinction between the law and the gospel. Click To TweetThe fact that faith is accompanied by love and “works by love” has no bearing on its role in justification in the Reformed tradition.[42] In comparison with the Reformed tradition’s relatively narrow definition of faith, Edwards’s definition of faith is much more expansive. At points, Edwards seems to want to amalgamate all “agreeing” or “consenting” dispositions and graces into justifying faith. In Miscellany #218, entitled “Faith, Justifying,” Edwards states the following:

‘Tis the same agreeing or consenting disposition that according to the divers [sic] objects, different states or manner of exertion, is called by different names. When ‘tis exerted towards a Savior, [it is called] faith or trust…when toward unseen good things promised, faith and also hope; when towards a gospel or good news, faith; when towards persons excellent, love; when towards commands, obedience; when towards God with respect to changes, ‘tis properly called resignation; when with respect to calamities, submission.[43]

This impulse in Edwards to bring faith, hope, love, and obedience into part of a dispositional amalgamation is clearly at variance with his inherited tradition. While not allowing faith, love, and obedience to be separated in experience, the Reformed tradition carefully distinguished between faith and the dispositional fruits of faith, especially love and obedience. This Edwards simply does not do.

Tomorrow, in Part 2 of this series, I will evaluate the role of obedience and perseverance in justification and ask whether Edwards strays further still from the Reformed tradition’s definition of sola fide.

Endnotes

[1] Jonathan Edwards, “Justification by Faith Alone” in The Works of Jonathan Edwards: Vol. 19, Sermons and Discourses, 1734-1738 (ed. M. X. Lesser; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 147-242. See esp. Lesser’s introduction. pp. 143-145.

[2] James W. Alexander, Forty Years’ Familiar Letters of James W. Alexander (ed. John Hall; New York: Charles Scribner, 1860), 1:221. An article published in Princeton’s Biblical Repertory and Theological Review had the same sentiments. See “Inquiries Respecting the Doctrine of Imputation,” Biblical Repertory and Theological Review 2 (1830), 455-456.

[3] Charles Hodge, Systematic Theology (New York: Charles Scribner, 1871-1873; repr., Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997), 3:116-117.

[4] Samuel T. Logan, Jr., “The Doctrine of Justification in the Theology of Jonathan Edwards” WTJ 46 (1984): 26-52, esp. p. 35; John H. Gerstner, The Rational Biblical Theology of Jonathan Edwards (Powhatan, Va., and Orlando, Fla.: Berea Publications and Ligonier Ministries, 1993), 3:208-212; John J. Bombaro, “Jonathan Edwards’s Vision of Salvation,” WTJ 65 (2003): 45-67, esp. p. 67; Jeffrey C. Waddington, “Jonathan Edwards’s ‘Ambiguous and Somewhat Precarious’ Doctrine of Justification?” WTJ 66 (2004): 357-372. See also Josh Moody, ed., Jonathan Edwards and Justification (Wheaton: Crossway, 2012); Hyun-Jin Cho, Jonathan Edwards on Justification (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2012); and Michael McClenahan, Jonathan Edwards and Justification by Faith (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2012).

[5] Thomas A. Schafer, “Jonathan Edwards and Justification by Faith,” CH 20, no. 4 (December 1951): 55-67; Perry Miller, Jonathan Edwards (New York: Meridian Books, 1959), 76; Anri Morimoto, Jonathan Edwards and the Catholic Vision of Salvation (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995); Gerald McDermott, Jonathan Edwards Confronts the Gods: Christian Theology, Enlightenment Religion, and Non-Christian Faiths (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000); W. Robert Godfrey, “Jonathan Edwards and Authentic Spiritual Experience” in Knowing the Mind of God: Papers Read at the 2003 Westminster Conference (London: The Westminster Conference, 2004), 25-45; George Hunsinger, “Dispositional Soteriology: Jonathan Edwards on Justification by Faith Alone,” WTJ 66 (2004): 107-120; Donald J. Westblade, “Calvinism in the Hands of an Not-So-Angry Jonathan Edwards” (paper presented at the annual meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society, Valley Forge, Pa., 17 November 2005). Conrad Cherry argues for points of continuity and discontinuity between Edwards and his Reformed tradition in The Theology of Jonathan Edwards: A Reappraisal (New York: Anchor Books, 1966), 41-43, 90-106.

[6] Gerstner, 3:206.

[7] Jonathan Edwards, “Quaestio” in The Works of Jonathan Edwards: Vol. 14, Sermons and Discourses, 1723-1729 (ed. Kenneth P. Minkema; New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 60-64.

[8] WJE, 19:149.

[9] WJE, 19:187-191, 196-199.

[10] WJE, 19: 192-196.

[11] WJE, 19:152-161.

[12] WJE, 19:185-186.

[13] “In interpreting Edwards on justification, much depends on what kind of focus one brings to the texts. If one brings a soft focus, Edwards can end up sounding very much like the Reformation, as he himself clearly intended and often, it should be added, carried out. If one brings a crisper focus…to the whole range of his texts, the picture comes out rather differently. …[the Reformed understanding] was the position from which Edwards always began and which he always intended to uphold as he thought his way into a more technical, complex, and subtle account that would do justice to his dispositional soteriology” (Hunsinger, 120).

[14] Standing at the head of the Reformed tradition is Calvin, whose Institutes Edwards no doubt read. While Edwards favored Peter Van Mastricht’s Theoretica-Practica Theologia to anything else, he also highly recommended Francis Turretin’s Institutes of Elenctic Theology. See John E. Smith, Harry S. Stout, and Kenneth P. Minkema, eds., A Jonathan Edwards Reader (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 304-305. Unfortunately, Mastricht’s Theologia Theoretica-Practica, which Edwards held to be “better than…any other book in the world, excepting the Bible,” has never been fully translated or published in English. The Dutch Reformed Translation Society, however, currently has a full translation effort underway and is planning to publish the massive Theologia Theoretica-Practica in its entirety.

[15] WJE, 19:148.

[16] WJE, 19:155.

[17] Francis Turretin, Institutes of Elenctic Theology (Phillipsburg, N.J.: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1994), 2:673-675.

[18] WJE, 19:153. While Edwards does not prefer to call faith the “instrument” of justification, he seems to be open to using this term in another construction. Says Edwards: “…if faith be an instrument, ‘tis more properly the instrument by which we receive Christ, than the instrument by which we receive justification.”

[19] WJE, 19:153.

[20] WJE, 19:155.

[21] WJE, 19:156.

[22] WJE, 19:157.

[23] WJE, 19:158.

[24] WJE, 19:159.

[25] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion (ed. John T. McNeil; trans. Ford Lewis Battles; Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1960), 1:737.

[26] Turretin, 2:563 (emphasis mine).

[27] Though outside the scope of this paper, it would be worthwhile to explore whether faith naturally results in legal union with Christ out of a “natural fitness” or whether faith results in legal union with Christ due to God’s gracious decision, rooted in a theological structure like the covenant of grace or the inter-Trinitarian covenant of redemption. Further reflection is needed to determine whether or not an explicit grounding of faith’s uniting power in the covenant of redemption or covenant of grace is essential to fully get rid of the specter of congruous merit. Godfrey, who writes from a Reformed perspective, believes that Edwards’s notion of natural fitness above is “problematic” (Godfrey, 36).

[28] WJE, 19:158. For a helpful discussion of faith, real union, and legal union in Edwards, see Waddington, 361-364.

[29] Turretin, 1:561, 568, 589.

[30] Calvin, 1:590.

[31] Calvin, 1:589.

[32] Calvin, 1:593.

[33] Turretin, 2:582.

[34] WJE, 14:60-61

[35] WJE, 19:160 (emphasis mine).

[36] Jonathan Edwards, “Charity and Its Fruits” in The Works of Jonathan Edwards, Volume 8: Ethical Writings (ed. Paul Ramsey; New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), 131.

[37] WJE, 8:139.

[38] WJE, 8:140

[39] Turretin, 2:581.

[40] Thomas Schafer, editor Edward’s “Miscellanies” (The Works of Jonathan Edwards: Vol. 13, The “Miscellanies” [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994]), concluded 1951: “…it is mainly Edwards’ concern for preserving orthodox forms of expression and for avoiding the conception of ‘merit’ which keeps him from a practically Roman conception of the place of love in justifying faith” (Schafer, 61). Waddington’s attempt to dismiss Schafer does not acknowledge or address the multiple quotations Schafer provides from Edwards himself showing the similarities between Edwards and the Roman Catholic understanding of faith and love (Waddington, 368-371).

[41] One in the Reformed tradition could agree with Edwards that there is an element of what might be called “love” (i.e. willingness to receive Jesus) in fiducia that is a part of the essence of faith, but love in this sense would need to be carefully distinguished from the love which is the greatest commandment of the law (Matt. 22:36) and which fulfills the law (Rom. 13:10). See Turretin, 2:562-563.

[42] Calvin states: “Indeed, we confess with the apostle Paul that no other faith justifies ‘but faith working through love’ (Gal. 5:6). But it does not take its power to justify from that working of love” (Calvin, 2:750).

[43] WJE, 13:344-345.