The Language and Theology of the “Free Offer”

By Paul Helm–

Christ, then, is the mirror in which we ought, and in which, without deception, we may contemplate our election….if we are in communion with Christ, we have proof sufficiently clear and strong that we are written in the Book of Life. (Calvin. Inst. 3.14.5)

The ‘free offer’ is one of those topics that occasionally arises among those who hold to the definiteness of the atonement, to eternal election and to the need for an effectual work of the Spirit in conversion. It has been a source of conflict at least since the Marrow Controversy and no doubt before that, and partly this is because those who deny or have serious reservations about the free offer fear being tarred with the brush of hyper-Calvinism.

The question is not must ministers of the gospel offer the gospel freely but may they? The issue is not must a minister always and without exception offer the gospel but may he? What is the ‘free offer’? Our chief task here is to try to get an answer to that question.

The language of the free offer

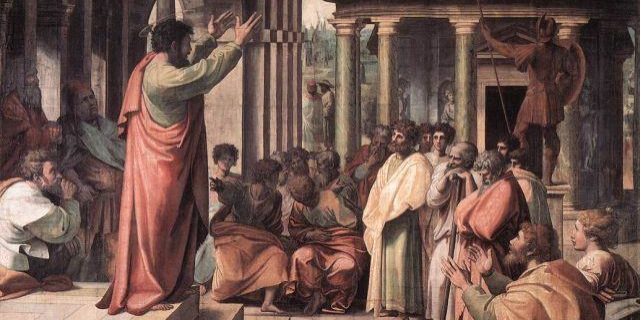

In one of his treatments of the free offer Professor John Murray writes of the ‘invitation, command, demand, overture and promise of the Gospel. ‘ (Collected Writings, Vol. I, 84) There is quite a range here, and few would argue that on biblical grounds that men and women should not be invited to Christ and presented with the promise of the Gospel. The question of whether the preacher should demand or command men and women to come to Christ seems more problematic. It seems to hit the wrong note, doesn’t it? The Gospel is good news. The idea that we have an obligation to hear and receive that good news, that it is a duty, seems odd. Perhaps this is one of those areas where faith and repentance, otherwise so closely allied, differ. That God commands all men everywhere to repent is part of the apostolic message. (Acts 17.30) Is it also part of that message to command all men everywhere to have faith, even though it is sinful to prefer darkness to light and not to believe on the only-begotten Son of God?

The case for the free offer

It is generally held that the free offer is necessary for evangelism, and that it is therefore part of a rounded gospel ministry.

There is first of all the basic fact that a preacher must not intentionally say something that is false. It is false that a fallen human being has the innate or natural ability to turn to Christ. He or she is in bondage to sin and needs to be released by the illuminating and regenerating work of Christ’s Spirit. The grace of the Spirit is not merely an aid which the sinner may accept or refuse, but when it comes it is effectual.

There is a difference, then, between saying that Christ will receive a person whenever he comes to him, and saying or implying that they have a natural ability to come to Christ whenever they choose to do so. So it would seem to follow, in order not to speak falsely, that those wishing to ‘offer’ the gospel must also affirm that fallen human beings are unable of themselves to come to Christ. So in the issue of the free offer, it is not so much what is said as what else is said, and built upon.

The word ‘offer’, which does not occur in the NT in connection with gospel preaching but is present in some catechetical documents – is suspect to some because it suggests the power to reject the offer. Offers may be refused, it is true, but it is also true there are some offers that are too good and too persuasive to be refused. So provided that the idea of innate ability is explicitly denied, there cannot be anything wrong with the use of the language of ‘offer’, surely. We must obey the law of God from the heart, but can’t. Christ offers his grace to sinners, but they can’t take it.

Secondly, it is necessary to preserve the freeness of justification by faith alone. The danger with those who hesitate about the free offer is that they are strongly inclined to interpose conditions. Christ’s words about the weary and heavy laden are turned into qualifications. ‘Am I weary and heavy laden? Am I weary and heavy laden enough?’ That is a bad move. It is bad move because it turns the attention of the person primarily on themselves, and on whether they fulfill certain qualifying conditions. If that move is encouraged then proclamations degenerate into descriptions of the state of grace. Of course one cannot avoid a certain amount of introspection. Even Calvin’s famous words about Christ being the mirror of election, the basis of Christian assurance, carry the idea of introspection.

But what is the positive case for the free offer? It seems to me that Professor Murray gets himself into unnecessary perplexities in the case that he presents. (Collected Writings Vol.4 113f.) The question for him is whether in offering (through his ministers) the grace of God in Christ, God may be said to desire the salvation of everyone, even of those for whom he has not provided salvation. Murray uses Matthew 5:44-8 as his chief biblical warrant for asserting that God does desire in this way, but of course the passage does not prove the point about desire, only that God provides sunshine and rain for those who do not deserve it.

It is certainly necessary to distinguish between the revealed and the secret will of God. But it’s a difficult area, made more difficult, it seems to me, by claims such as Murray’s that in the free offer God reveals a desire for the salvation of men and women whom (God alone knows) are reprobates. Which naturally leads us to ask, how can God publicly and sincerely desire what he does not secretly will?

Why is there need to go down this particularly tortuous path in the first place? For the free offer is the offering of Christ to anyone, not to everyone. The gospel is to be preached indiscriminately, and unconditionally, in order that God’s elect (presently unknown) may be effectually called by the word of grace and brought to penitence and faith. The preacher does not know who will respond, and he must (following the Great Commission) play his part in preaching the gospel to every nation. It seems to me that the language of unconditionality and freeness, declared in a warm and urgent way, suffices for the offering of the gospel freely; it integrates with other doctrinal elements in the faith, it does not turn people in on themselves in concern as to whether or not they are ‘qualfiied’ to come to Christ, and it does not get us unnecessarily entangled in the secret and the revealed will of God. It is not part of the presentation of Christ freely to say that God sincerely desires the salvation of everyone, and to say such a thing makes preaching sermons on definite atonement and eternal election all the more difficult, leading to unnecessary perplexity.

(Interestingly, in another discussion of the ‘free offer’, written nearly twenty years later, Murray restricts himself to writing in terms of indiscriminate or unlimited overtures of grace. (Collected Writings I. 81))

Gill on the free offer

Finally, a few remarks on John Gill on the free offer. As Nettles shows, Gill upholds the vigorous preaching of the gospel, and the urging of men and women to come to Christ. (101). But he has some idiosyncratic touches of his own. I will mention one. He has a theological objection to the offering of Christ or his grace by a minister (Nettles, 100), for (Gill says) only God can give grace, and he does not do so by offering it, but by sovereignly bestowing it. Gill holds that God alone grants grace, and therefore that it is improper to suppose that ministers of the gospel may offer Christ. He is not theirs to offer. The grace of God is bestowed on the elect, and grace is not offered to the non-elect. (The Cause of God and Truth, 288-9)

Of course the NT teaches that preachers of the gospel proclaim in the name of Christ and are his representatives. ‘We are ambassadors for Christ, God making his appeal through us….’ (2 Cor. 5. 20) So when they preach, God preaches through them. But they are not, literally, in the place of God. They are not the bestowers of grace, nor are they the judges of men and women. (I Cor. 4.5) Another significant difference is that preachers do their work ‘blind’. They do not know whether, when they preach, their audience will hear, or forbear. Like Paul in respect of his own people, who had a strong desire for them to be saved, and could wish that he himself might be accursed and cut off from Christ for the sake of his others (Rom. 10.1, 9.2-3), so ministers may have desires for the salvation of their hearers that (unknown to them) do not accord with God’s decree. So while Gill is perfectly correct to say that grace is not bestowed on the non-elect, yet it may be offered to them by ministers of the gospel out of (what we might call) ‘blind compassion’. So we might say that Gill’s point might, with Scriptural warrant, be turned around. God does not offer grace to the non-elect. So there is ‘no falsehood or hypocrisy, dissimulation or guile, nothing ludicrous or delusory in the divine conduct towards them’. (289) But his ministers might, from their lowlier position, offer the grace of the gospel indiscriminately, and there’s nothing hypocritical or ludicrous about that either.

Paul Helm was educated at Worcester College, Oxford, and was for many years a member of the Philosophy Department of the University of Liverpool. From 1993-2000 he was the Professor of the History and Philosophy of Religion, King’s College, London. In 2001 he was appointed J.I. Packer Chair of Philosophical Theology at Regent College, Vancouver. He is presently a Teaching Fellow there. Helm is the author of numerous journal articles and books. Some of his most well-know books include Calvin and the Calvinists, Faith and Reason, The Trustworthiness of God, The Providence of God, Eternal God, The Secret Providence of God, The Trustworthiness of God (with Carl Trueman), John Calvin’s Ideas, Calvin at the Centre, and Calvin: A Guide for the Perplexed.