Francis Turretin on Faith and Reason

By Paul Helm–

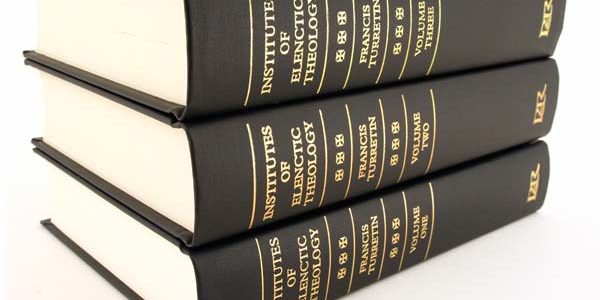

I‘m not sure why it is the case that fewer systematic theologies were produced in the UK during the Puritan era than on the continent, particularly in Holland but also in Geneva. Continental theologies are very thorough, dealing not only with the various loci of theology but also, under prolegomena, discussing the place of reason and the senses in the work of theology in general terms. Francis Turretin is a good example. So he gives his readers a general account of the place of logic, reason and judgment in theology at the beginning of his Institutes. In Book I questions 9-11 he outlines what he takes to be the role of reason in theology, and in question 12, the role of the senses, albeit in his usual compressed and economical way. In the light of current ferment about foundationalism and its alleged evils I think that it is helpful to regard Turretin not as an epistemological foundationalist in the optimistic Enlightenment sense of providing self-evident proposition or propositions as foundational, like Descartes’ cogito, or providing undeniable foundational data, like John Locke’s simple ideas, ideas of sensation and reflection, but as thinking of the senses and intellect as fundamental instruments of knowledge. And intrinsic to his account of the place of the reason and the senses in theology is the claim that grace builds upon nature.

Nature and grace

Writing of what Paul says about the captivity of our thought to Christ (2 Cor. 10.5) Turretin writes: ‘He [Paul] does not therefore mean to take away the reason entirely because grace does not destroy, but perfects nature. He only wishes it to serve and to be a handmaid of faith and as such to obey, not to govern it as a mistress….’ (I.31) This idea that grace builds on nature may not make him friends with the more fideistically-inclined Reformed folk. Nevertheless this is the historic position of the church back at least as far as Augustine. The phrase is not to be understood as an endeavour to naturalise Christian theology, as if the materials of that theology are to be drawn from nature. Grace builds upon nature by, for example, not denying the powers of the human intellect and the senses. Jesus was not a fideist or a gnostic, any more than he was a sceptic. As his sufferings involved the pain and agony of his human body, so his teaching employed all the powers of his human nature, which in turn appealed to the senses and intellects and imaginations of his hearers. He uses human reason, and appeals to what his disciples may see and touch, as with Doubting Thomas. Such facts do not deny the effects of sin on human nature any more than they make the illuminating, regenerating activity of the Holy Spirit unnecessary. The fact that the Apostles had seen, heard and touched the Messiah was an intrinsic part of the Apostolic testimony, to show that the Christian Gospel is not a ‘cleverly devised myth’ ‘He that has ears to hear, let him hear’.

The subordinate place of reason

In the remainder of this post I shall look at something of what Turretin has to say about the place of reason in answering Question 9, Does any judgment belong to reason in matters of faith? Or is there no place at all for it? In brief, his answer is that reason has a real but subordinate role. It exercises what he calls the ‘judgment of discretion’ in matters of faith. That is, in weighing up evidence and in drawing inferences from Scripture. Here Turretin refers to the reason that is to be employed in such work as ‘rightly instructed.’ By this he means reason enlightened by the Holy Spirit. But even this does not warrant those who possess such judging or arbitrating of the controversies of the faith, because reason plays a subordinate role.

He makes a distinction between reason’s role in helping to establish the truth of propositions known by nature, and known by the word of God. In the case of the propositions of the word of God reason has a secondary rule. Where the word includes ‘something unknown to nature’, that is, unknown to natural reason’ – I presume that this is a reference to miracles – then reason ought not to pass judgment on this, but only the word. Much more so is reason subordinated to revelation in the case of the mysteries of the faith. So while he is emphatic that the mysteries far exceed our comprehension, and that reason is ‘slippery and fallible’ unless enlightened by the Spirit, there is nevertheless a real if subordinate place for it in understanding what has been revealed.

To begin with, there are propositions that the reason intuitively recognizes the truth of, such as the whole is greater than the part, an effect supposes a cause, and it is impossible for something both to be and not to be at the same them. Without the recognition of these there could be neither science nor art nor certainty about any thing. And these first principles, as he calls them, are true not only in the realm of nature, but also in the mysteries of the faith. Faith borrows these from reason, and uses them to strengthen its own doctrines, (that is, to prevent them from being misunderstood).

Reason therefore does not provide us with theological norms, and so our faith does not become a mixture of philosophy and theology, for the principles of reason do not afford us with the foundation and principles of faith, but have an instrumental and therefore a subordinate role.

At this point Turretin distinguished between reason and right reason. This is already anticipated by what he has said about rightly instructed reason. From some of the things he says, right reason may be reasoning in accordance with the results of natural religion. In any case it means at least right creaturely reason, reasoning from the standpoint of admitted creatureliness, a standpoint that recognizes the limitations of human, creaturely reason due to ignorance and finitude. The right reasoner does not complain when he cannot comprehend the mysteries of the faith, nor does he seek to overturn the first principles of natural religion and to establish errors of his own. As a result, right reason subordinates itself to the revealed mysteries, and to the understanding of them (or the preserving of them from misunderstanding) as best it can. I do not think that Turretin held that the recogniton of such reason, or a willingness to possess it, is necessarily the immediate fruit of regeneration, for it may be held at times generally in the culture, and so be a part of ‘public doctrine’.

In the formulation of the place of reason and particularly of the senses in the understanding and elucidation of the faith, a crucial role seems to have been played by controversies over the nature of the presence of Christ in the Supper, both the Lutheran doctrine of the ubiquity of Christ’s presence and the Roman doctrine of transubstantiation. We shall look at this side of things in a further post.

Paul Helm was appointed J.I. Packer Chair of Philosophical Theology at Regent College, Vancouver, in 2001. He is presently a Teaching Fellow there. Among his many books are Calvin and the Calvinists, Faith and Reason, The Trustworthiness of God, The Providence of God, Eternal God, The Secret Providence of God, The Trustworthiness of God (with Carl Trueman), John Calvin’s Ideas, Calvin at the Centre, and Calvin: A Guide for the Perplexed.