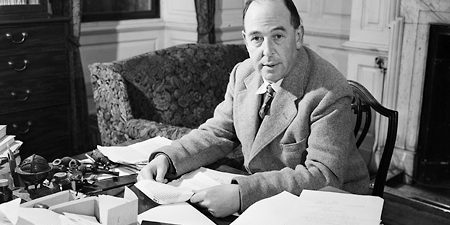

Getting C. S. Lewis Wrong (Matthew Claridge)

P.H. Braizer. C.S. Lewis: Revelation, Conversion, and Apologetics (C.S. Lewis: Revelation and the Christ). Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2012.

Review by Matthew Claridge–

What is the measure of a man like C.S. Lewis? Certainly, there have been greater theologians, greater philosophers, greater writers, greater apologists, greater literary critics, greater churchmen; but who can ever have been said to be “great” in all these areas? He was truly a “Jack” of many trades, and arguably a master of quite a few of them.

Exploring the vast and varied thought of C.S. Lewis is somewhat analogous to making one’s way through the writings of Martin Luther. Neither one ever composed a definitive guide to their theological views. Their written corpus is made up of varied sorts of material: apologetic tracts, treatises of more studied reflection, public addresses, and an extensive store of personal letters (in Lewis’s case, we also have imaginative fiction, regrettably perhaps something Luther never indulged in). Stating the definitive view of Lewis or Luther on any given subject runs the further risk of not taking into account how their views evolved over the course of their lives.

For these and other reasons, it seems all the more appropriate and necessary for someone to attempt a “systematic” analysis of these two titans of the faith. Such works are common enough in the case of Luther, but not nearly as much in Lewis’s case. P.H. Brazier is now attempting to close that gap with a four volume systematic analysis of Lewis’s theology published by Pickwick. Three of these volumes are now published including: vol. 1, C.S. Lewis—Revelation, Conversion, and Apologetics; vol. 2, The Work of Christ Revealed, and vol. 4, C.S. Lewis—An Annotated Bibliography, and Resource. The third volume still awaits publication, vol. 3, The Christ of a Religious Economy.

For these and other reasons, it seems all the more appropriate and necessary for someone to attempt a “systematic” analysis of these two titans of the faith. Such works are common enough in the case of Luther, but not nearly as much in Lewis’s case. P.H. Brazier is now attempting to close that gap with a four volume systematic analysis of Lewis’s theology published by Pickwick. Three of these volumes are now published including: vol. 1, C.S. Lewis—Revelation, Conversion, and Apologetics; vol. 2, The Work of Christ Revealed, and vol. 4, C.S. Lewis—An Annotated Bibliography, and Resource. The third volume still awaits publication, vol. 3, The Christ of a Religious Economy.

At the outset it should be noted that this is not a true “systematic theology” in a traditional or complete sense. Brazier explains: “This is a series of books which have a common theme: the understanding of Christ, and therefore the revelation of God, in the work of C.S. Lewis” (back cover). Perhaps to be more technically precise, this is a work of “Dogmatics,” i.e., a study of the whole of C.S. Lewis’s theology through the lens of one particular loci, namely, Christology. We might say it is a study of the ways Lewis’s Christology impacted and influenced all other areas of his theological musings. Whether this is the best or most successful way of going about the task of analyzing Lewis theology is an open question.

The present review will focus on the first volume in Brazier’s series, C.S. Lewis—Revelation, Conversion, and Apologetics. The best description of this volume, I believe, is an overview of Lewis’s Christology. It is composed of three sections. The first and third offer a more diachronic analysis, discussing how Lewis’s Christology developed over time first existentially (his conversion, Part 1) and then intellectually (a chronological survey of all his literary output, Part 3). The second Part focuses on Lewis’s methodological priorities, namely, his pursuit of “mere Christianity.” Here Brazier is attempting to locate the “sources” of Lewis’s theology; what Lewis considered authoritative to fill in the content of “mere Christianity.”

Commendations

My analysis of this first volume consists of two parts: commendations and critiques. Let’s begin with the former. First, Brazier is a sympathetic reader of Lewis, indeed a champion for Lewis, which means he will be more willing to read Lewis charitably and on his own terms. This extends only so far, however, as we’ll see shortly. Second, Brazier has clearly done his homework and is thoroughly conversant with Lewis’s corpus. One happy result of this is that he brings to the reader’s attention material that arm-chair Lewis lovers like myself were unaware of. For instance, Brazier cites an interview Lewis conducted with a representative of the Billy Graham Association just a few months before he died. The content of that interview is quite illuminating. Brazier often resurrects other out-of-the-way personal correspondences that cast much light on Lewis’s views. Where once I thought Lewis was silent on a matter, Brazier, having scanned the wide and far-flung extremities of Lewis’s writing output, reveals the range of subjects Lewis had interacted with. A Fourth strength is more mundane but nonetheless quite helpful. Brazier is careful to head each chapter with a full synopsis of what follows. Considering the difficult time one has in following Brazier’s train of thought at times, this was a great aid. Finally, of a more substantive nature, Brazier’s interaction with N.T. Wright’s critique of Lewis’s view of the atonement was quite fascinating.

The work Brazier has put into these volumes is impressive and the result of much toil and integration. I do not want to minimize that achievement in any way. Nonetheless, I do have several problems with this first volume, many of a systemic nature.

Critique

Critique

As a more “Reformed” evangelical, it goes without saying that there are going to be aspect of Lewis’s theology with which I disagree. Yet one of the great difficulties in reading this volume is determining when I am disagreeing with Lewis and when I am disagreeing with Brazier. There is an overall lack of clarity and precision which often results in ascribing doctrinal and philosophical positions to Lewis that haven’t been fully demonstrated. The most glaring of these is the “christological” lens through which Brazier reads Lewis. Brazier’s Christology, never mind Lewis’s, is highly indebted to Karl Barth. Barth’s de-historized “Christ-event,” or “perpetually-incarnated-Christ” model is simply assumed at the outset and then super-imposed over Lewis’s thinking at every point. Whenever Brazier mentions the word “revelation” in his book, one must understand it in a Barthian way (as he says on the very first page: “To talk about Jesus Christ is to speak of revelation—God’s self-revelation, God’s revealedness to humanity.”)

This becomes very explicit in the first section of the book where Brazier compares Lewis’s conversion experience to Barth’s. The fact that Brazier chooses Barth as a comparison is significant enough. But Brazier’s very extensive treatment of Lewis’s conversion (nearly half the book) is puzzling until one realizes how significant the nature of “religious experience” is in a Barthian framework. Consider this statement: “the measure of all religious experience has to be the self-revelation of God, which is in Christ Jesus. How does a religious experience measure up against he gospel? The conversion of Lewis and Davidman are … valid …first, because in each case the Spirit drew each of them to the knowledge of God’s self-revelation in Christ; second, the way they lived their lives after the encounter is testimony to the truth of God’s revelation” (61). What’s left out here or at least blurred is the role faith in the historic work of Christ and the epistemological priority of Scripture. Instead, conversion is an instance of existential realization of the “universal Christ.”

Consider Brazier’s assessment of the Reformation: “The reformation was a heightening of church, a return to biblical roots and the theology of the patristic era, but it was also the death-knell of universality and further enhanced what to many appears to be the elevation of human-centered religion over the revelation of God” (104). It is incomprehensible how Brazier can pit the Reformation’s “return to biblical roots” with a downplay of the “revelation of God” without a corresponding Barthian spin. Regardless of whether Lewis’s Christology is more or less Barthian, I think Brazier would have served the reader better by simply using Lewis’s own categories and terminology as much as possible. After all, Lewis knew virtually nothing of Barth. Why not locate Lewis’s Christology in the sources he was aware of and indebted to?

Another irksome example of this sort of thing is Brazier’s insistence that Lewis was a full blown Platonist. Now, this fact does not play as significant a part in Brazier’s analysis of Lewis as the pair of Barthian spectacles he uses, but it does come up frequently and without argument. There is indeed a good case to be made that Lewis held strong platonic views, but Brazier never actually demonstrates this. Surely, anyone attempting a systematic analysis of Lewis would make this a major area of focus and discussion.

These are the most brazen of Brazier’s overlays. Similar but slightly different problems emerge on other fronts. One gets the impression that Brazier is often over-systematizing things that Lewis was less than systematic about. Two examples are Brazier’s discussion of salvific inclusivism and “prevenient grace.” What’s frustrating here is that, again, Brazier sprinkles his account with various statements that develop Lewis’s inclusivism but never gives it a focused treatment. For instance, at one point Brazier argues: “In the case of people who were born outside of the knowledge of the incarnation-cross-resurrection, the ultimate test of the validity of a conversion experience is post mortem, after death, before the judgment seat of Christ” (61-62). This statement pops out of the blue, and it is not clear if this is Brazier’s own view or Lewis’s. Brazier has not convinced me that Lewis had developed his “inclusivism” thoroughly enough to make such a dogmatic assertion.

What Brazier does with the concept of “prevenient grace” is far more egregious. This concept is pervasive to Brazier’s interpretation of Lewis and I am not at all convinced Lewis held to it in the kind of rigorous, systematic way Brazier suggests. Brazier defines it in a classically Arminian way: “Because of our fallen status, corrupted through original sin, prevenient grace permits people to respond, to accept or not, God’s salvation proffered through Christ’s sacrifice.” (94) Did Lewis ever make this subtle distinction? Brazier never clarifies whether Lewis was aware or had traced the history of this theological idea. Brazier further states at one point that prevenient grace is an “Augustinian” concept that Lewis “drew from” (pg. 210). There is no evidence cited to support either side of this claim.

I suppose one test whether Lewis’s view could be described or interpreted as Arminian would be his view of free will and divine sovereignty. On this score, Lewis’s statements are decidedly mixed. Remarkably, Brazier collects quite a number of statements from Lewis’s pen that lean in a Calvinist direction. His interview with the Billy Graham agent at the end of his life is one perfect example. Reflecting back on his conversion and the statements he made in Surprised by Joy regarding his “decision” for Christ, Lewis muses:

Everyone looking aback on his own conversion must feel … ‘It is not I who have done this. I did not choose Christ he chose me. It is all free grace, which I have done nothing to earn.’ That is the Pauline account: and I am sure it is the only true account of every conversion from the inside. Very well. It then seems to us logical and natural to turn this personal experience into a general rule, ‘All conversions depend on God’s choice’ (94).

Brazier then interprets this as an argument in favor of prevenient grace. Not so fast. Lewis’s words could just as easily be read in a thoroughly compatibilist way (i.e., Calvinist way). My feeling is that Lewis was not familiar with the full range of theological options here. Sadly, I doubt he had read Jonathan Edwards’ The Freedom of the Will. At minimum, Lewis accepted the Calvinist move to only go so far as Scripture itself allows in trying to unravel the mysteries of election: “The real inter-relation between God’s omnipotence and Man’s freedom is something we can’t find out … I find the best plan is to take the Calvinist view of my own virtues and other people’s vices: and the other view of my own vices and other people’s virtues” (95).

Another area of concern is how Brazier often assumes that Scripture plus the Fathers and the creeds operate as equally authoritative in Lewis’s mind. I do not believe Brazier has sufficiently proven this strong claim simply because Lewis was concerned to recover “mere Christianity” from the consensus of doctrine found in the early church.

In summary, this first volume, I’m afraid, is not very systematic. Several key concepts are spread out all over the work and never brought together under one head. The structure of Berhard Lohse classic Martin Luther’s Theology I believe would have served Brazier’s goals much better—a section analyzing the development of Lewis’s theology over time (diachronic) followed by a section utilizing the classic theological loci to outline his theology in a more synchronic way. The subsequent volumes in Brazier’s series hold out the hope of following a more synchronic approach.

Once again, there is a wealth material in Brazier that will interest any serious student of Lewis. This volume has certainly given me a more well-rounded view of Lewis’s views on a number of subjects (his view of the atonement, Roman Catholicism, and the End Times were particularly interesting). Often, however, these discoveries were made simply by exposure to Lewis’s own words, not Brazier’s commentary.

Matthew Claridge is an editor for Credo Magazine and is Senior Pastor of Mt. Idaho Baptist Church in Grangeville, ID. He has earned degrees from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He is married to Cassandra and has two children, Alec and Nora.