Is the God of The Shack the God of the Bible?

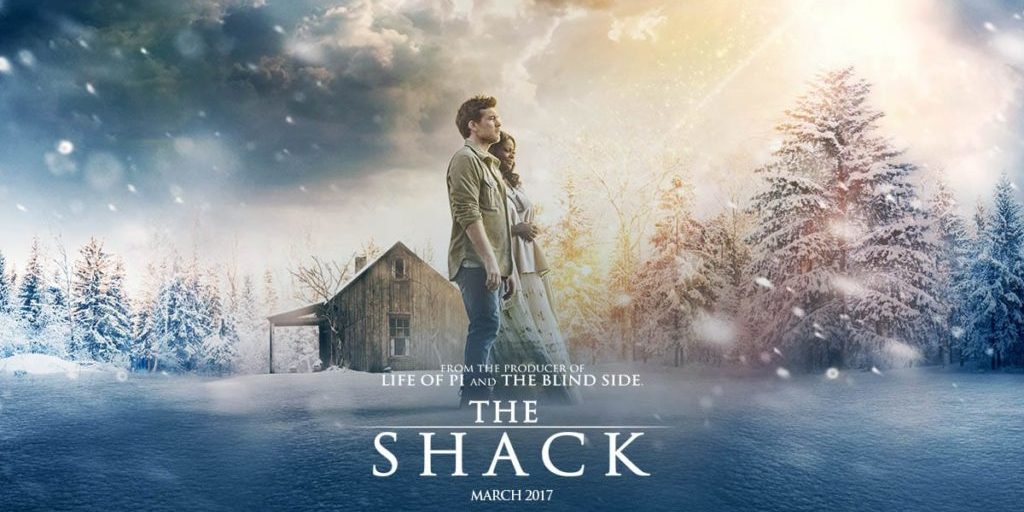

The Shack, written by William Paul Young, came out several years ago and instantly become somewhat of a phenomenon selling millions of copies. In fact, it is one of the best-selling paperback books of all time, with readers who are enthusiastic for the message it communicates. I never had any desire to read it at first. To be honest with you, I am not a huge fiction reader. I read a lot, just not a lot of fiction. Beside the point, as the movie based upon this book releases, I decided to pick up The Shack to see what all of the hype was about.

The Shack has the ability to draw the reader in with a very emotional story about a man named Mack. Mack is struggling with reconciling God and the problem of evil after he loses his 7 year old daughter Missy when she is brutally kidnapped and murdered. The storyline itself has the ability to tug at anyone’s emotions when you consider the family dynamics that are in play. Mack comes from an abusive home, went to seminary as a young man, married and has five children. But when he loses his youngest daughter, “The Great Sadness” takes over. It is not until he returns to the shack where his daughter was murdered that he begins to find a sense of healing.

In the shack, Mack meets the divine Trinity represented as “Papa” who is an African-American woman revealing the father; Jesus, a middle-eastern man; and “Sarayu,” an Asian woman who is revealing the Holy Spirit. Then in chapter 12, you meet another character who is called “Sophia” who is meant to be the personification of wisdom from the book of Proverbs, but in reality, seems to function as another member of the Godhead. Now for some, this type of portrayal of God likely caused them to tune out, as it should. Nowhere in the Bible is God ever portrayed as a woman and the conversations that she and the other members of this trinity have with one another are often times awkward at best. But if you continue on through this book, you should notice many other theological flaws that unfortunately cause this work of fiction to be heretical in much of its content.

One of the underlying issues with The Shack is the confused view of hierarchy and authority. The first red flag for me on this issue came in the quote at the top of chapter 6, “No matter what God’s power may be, the first aspect of God is never that of the absolute Master, the Almighty. It is that of the God who puts himself on our human level and limits himself.” Young even says that as the Godhead submits to one another, so too they are “submitted to you in the same way.” (145) Young offers no biblical proof for this view, yet it plays through the entire book and in how Mack interacts with the Trinity. This helps to also explain the difficulties presented in Young’s view of God’s sovereignty and free will.

How our wills function in light of God’s sovereignty has been debated for centuries. There is generally an accepted range that we can have on these topics while still affirming the absolute authority of God as well as the call for man to respond and act in faith. The Shack falls outside of that accepted range. God appears to be more of a master strategist than he does the creator of the world. As “Papa” is talking to Mack, she says, “We carefully respect your choices, so we work within your systems.” (123) In these continued interactions with Mack, God appears to be constrained by our choices as he is not necessarily in control, but merely uses our circumstances for our good. As Sophia tells Mack, what happened to Missy “was no plan of Papa’s.” (165)

This then flows into how Young communicates his view on forgiveness and salvation. On page 225, “Papa” tells Mack, “Forgiveness does not establish relationship. In Jesus, I have forgiven all humans for their sins against me, but only some choose relationship.” According to the Scriptures, this is simply not true. In 1 John 1:9, it is only to those who confess their sins who are forgiven and unless we repent, according to Luke 13:3, we will perish. Forgiveness is conditional. For it is only to those “who call on the name of the Lord” that are saved (Rom. 10:13). What Young gives to us is a universalistic view of salvation where repentance is optional and everyone is forgiven. This is seen in Mack’s vision of his abusive and likely unrepentant father who is in heaven. Or in how Mack is already forgiven before he even asks for it. Then it is implied when Jesus responds to Mack’s question about all roads leading to him. Jesus says, “most roads don’t lead anywhere” but “I will travel any road to find you.” This explains earlier when Jesus said, “Those who love me come from every system that exists. They were Buddhists or Mormons, Baptists or Muslims, Democrats, Republicans…I have no desire to make them Christian…” (182). But this makes since if everyone is already seen as a son or daughter (162) and if God does not punish sin, since sin is its own punishment (120).

What is meant to be viewed as a comforting explanation for an emotionally distraught character, actually presents more problems. Young presents a god who is separated from tragedy, limited in regards to our decisions and doesn’t punish evil and sin. He gives us a very mystical way to view God that is not only separated but in many places is contrary to the Scriptures. I will not be seeing this movie this weekend as I have no desire to have the immortal, invisible God pictured in this way before me as will be on the big screen. But if you do go and see it, I caution you to do so with great discernment “ready in season and out of season” (2 Tim. 4:2) to “give a defense to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you.” (1 Pet. 3:15)

Michael Nelson is the pastor of First Baptist Church in Grandview, MO.