Who is afraid of Thomas Aquinas? A reply to Scott Oliphint, part 1 (Paul Helm)

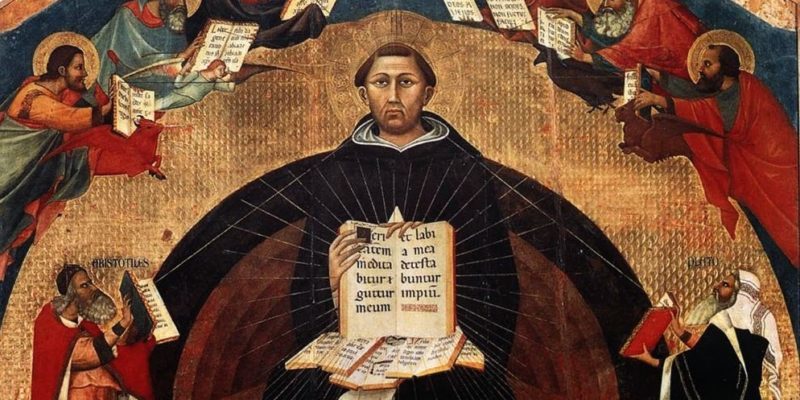

Here is an account of the thought of Thomas Aquinas (1225-74), one of a new series on Great Thinkers published by P&R Publishing.[1] Aquinas wrote extensively on theology and philosophy, as well as being a biblical commentator. He was a major influence on the rise of scholasticism, which both affected Roman Catholic thought from the fourteenth century onward and which was in turn influential on Reformed Protestantism, particularly in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. So, it is appropriate in more ways than one that we should pay attention to him and his legacy.

thought of Thomas Aquinas (1225-74), one of a new series on Great Thinkers published by P&R Publishing.[1] Aquinas wrote extensively on theology and philosophy, as well as being a biblical commentator. He was a major influence on the rise of scholasticism, which both affected Roman Catholic thought from the fourteenth century onward and which was in turn influential on Reformed Protestantism, particularly in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. So, it is appropriate in more ways than one that we should pay attention to him and his legacy.

Approaching the Summa Theologiae

Scott Oliphint, Professor of Apologetics and Systematic Theology, Westminster Theological Seminary, Philadelphia, has a tall order, which he has approached rather idiosyncratically. Faced with the massive body of Aquinas’s writing, Oliphint has chosen to select material almost exclusively from Part I of the Summa Theologiae (ST), Question 1 on the nature of theology, proofs for the existence of God (Question 2), and on the nature of God, chiefly his simplicity (Question 3). He sees Thomas exclusively through the lens of foundational apologetics, that is, as someone who uses rational proofs of God’s existence as the foundation of Christian theology.

However, someone approaching this great work at the beginning (from Question 1), will note that Aquinas does not begin his theological discussion to follow on with apologetics. Rather, he prepares a Christian readership with a basic discussion of articles, or questions, about theology itself, such as: Is theology necessary besides philosophy? Is theology a science? Is it a theoretical or practical endeavor? How does it compare with other sciences? Does it set out to prove anything? What is its attitude toward the “sacred writings”? Is God the subject of this science? Is this teaching probative? Should holy teaching employ metaphorical or symbolical language? Can one passage of Holy Scripture bear several senses? Discussion of these questions ends the articles of Question 1. At least some of these questions, I dare say, are unfamiliar these days.

Question 2, entitled “The Existence of God,” has several articles that arise from the discussion of Question 1. This leads to the following: “Whether the existence of God is self-evident?”, “Whether it can be demonstrated that God exists?”, and “Whether God exists?” The answer to this final question contains his famous “Five Ways” of proving God’s existence, followed (in Question 3) by a discussion on the simplicity of God. This entails the following questions: Is God a body? Is he, that is to say, composed of extended parts? Is he composed of form and matter? Is God to be identified with his own essence or nature, with that which makes him what he is? Can one distinguish in God essence and existence? Can one distinguish in God genus and difference? Is he composed of substance and accidents? Is there any way in which he is composite, or is he altogether simple? Does he enter into composition with other things? These are strange questions to our minds.

Aquinas’s discussion of divine simplicity is particularly significant in that it is a notion that is entailed both by his opening remarks on the articles of Christian theology and his proofs of God’s existence. Prior to the occurrence of the Five Ways in Question 3 of Part One, Thomas tells us in more than one place that God cannot be known as he is in himself, but by what he brings about, his effects.

He points out in 1a 1.7 that we cannot know what God is but by some effect or effects of nature or grace. For God cannot be defined. He reiterates the point in 1a 2.1, and it is expanded further in 1a 2.3. Shortly after this point, he comes to the Five Ways which are five arguments from effects to their divine cause.

Oliphint ignores almost everything else that Aquinas wrote, both in the ST or elsewhere, and what he reflects on he does not do a very good job.

Regarding some of these apologetic questions, there is great pressure to think that the proofs of God’s existence that Thomas sets forth in ST, 1a 1.2.3[2] referred to as the Five Ways, are foundational to the existence of the articles of faith, the doctrines of the Christian faith, such that everyone committed to the articles has first to be committed to the proofs. But this is a mistake, as we shall see. This pressure does not come from Aquinas himself, but from the way in which his proofs of the existence of God have become separated from the body of his theology, as rational “proofs” in the Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment sense. Aquinas rarely refers to “foundations” in the modern sense, though they figure prominently in Oliphint’s account of him.

Oliphint underscores this, incidentally, by pointing out that several different versions of the proofs are extant in Thomas’s writings (56-57). This suggests a philosopher working on arguments that he is not altogether satisfied with, rather than with someone aiming at canonical finality. The reference to Exodus 3:14 in the proofs (1a 2.3) does not detract from their philosophical character in the ST; rather, it shows them to be a philosophical project whose aim is to demonstrate that a conclusion, namely, that God exists, is not only reasonable but is also consistent with the God of revelation.

It is a great pity that the author has not given to his readers some idea of the sweep of Thomas’s philosophical and theological ideas. He has also decided to pay very little attention to the different ways in which he has been influential in the history of theology subsequently, both in Roman Catholicism and in Protestantism. In this review, we shall be following him in his largely unsatisfactory discussion of material in the first articles of Book I of the ST, which he treats in an avowedly ahistorical way (2-3). This extends to the idea of apologetics itself, which Aquinas hardly mentions.

Oliphint’s Approach

In starting his treatment of Aquinas in his book with Part One, Question 2 of the ST, and ending it at Question 3, I believe that the significance of Question 1 is missed. After a brief Introduction to Aquinas’s life and work, his book has two main chapters (“Foundation of Knowledge” and “Foundation of Existence”) derived from Oliphint’s estimate of the proofs, rounded off by a Conclusion. By this time the reader is aware that the author’s interest in his material is almost wholly conditioned by his interest in apologetics as it is taught in a modern evangelical seminary, and in particular the apologetics of the late Cornelius Van Til, not with understanding Aquinas historically, on his own terms. If we pay attention to what Thomas asserts and implies in Question 1, then it becomes obvious that Oliphint’s treatment is thoroughly askew of what Aquinas is endeavoring.

Once he starts reading the ST, the reader will notice at once the place of Scripture as a prime theological authority in Question 1: 2 Timothy 3:16, Isaiah 64:4, 2 Thessalonians 3:2, James 2:3, Proverbs 9:3, Isaiah 11:2, Deuteronomy 4:6, 1 Corinthians 3:10, Proverbs 10:23, Romans 1:19, 1 Corinthians 10:4-5, 1 Corinthians 2:15, John 20:31, Titus 1:9, 1 Corinthians 15:12, Hosea 11:10, Romans 1:14, Matthew 7:6, Hebrews 7:19, and Matthew 19:8 are carefully cited. We shall consider the significance of the authoritativeness of such citations later, but from the start, the Summa is to be regarded as a Christian production.

In the course of the treatment of this Question a number of significant contrasts are also introduced. For example, “Hence the necessity for our welfare that divine truths surpassing reason should be signified to us through divine revelation.” “[T]he rational truth about God would be reached only by few, and even so after a long time, and with many mistakes.” “[T]here is nothing to stop the same things from being treated by the philosophical sciences when they can be looked at in the light of natural reason and by another science when they are looked at in the light of divine revelation. Consequently, the theology of holy teaching differs in kind from that theology which is ranked as a part of philosophy” (ST, 1a 1). Here Thomas compares philosophy to theology to the disadvantage of the first. These expressions bear on the relation of the nature of the proofs to the articles of theology.

So, it is Thomas’s view that revealed theology is in many ways superior to rational theology. What he refers to as “theological articles” presuppose the existence of God. But the existence of God is not one of the articles of faith. Rather, it is presupposed by every one of the articles. Because of the greater certitude and worthiness of its subject-matter, theology is the noblest of the sciences. The topic of natural theology can achieve demonstration about God without faith and may involve mistakes. So, there is a rather complex relation between the two.

Besides this emphasis on Scripture, and hence on the Christian character of the entire work, Aquinas informs his readers early on that there are within the project two kinds of what he calls scientia, an orderly body of knowledge. These are two because there is scientia from “the innate light of intelligence” and then there is the scientia “recognized in the light of a higher science.” I suppose Christian apologists must recognize that “personal foundations” differ often in marked ways from person to person in those who are engrafted into Christ (e.g., the Philippian jailer differed from Lydia the seller of purple, Zaccheus from Nicodemus, Peter from Paul). The demonstration of God’s existence is a science, as is Christian theology, founded as it is on the Scriptures and on the teaching and preaching of the church. Click To Tweet

In this second manner is Christian theology a science, for it flows from founts recognized in the lights of a higher science, namely God’s very own which he shares, with the blessed. Hence, rather as [musical] harmony credits its principles which are taken from arithmetic, Christian theology takes on faith its principles revealed by God (ST 1a 1.2).

So, the demonstration of God’s existence is a science, as is Christian theology, founded as it is on the Scriptures and on the teaching and preaching of the church.

We also stand in need of being instructed by divine revelation even in religious matters the human reason is able to investigate. For the rational truth about God would be reached only by few, and even so after a long time and mixed with many mistakes; whereas on knowing this depends on our whole welfare, which is in God. In these circumstances, then, it was to prosper the salvation of human being, and the more widely and less anxiously, that they were provided for by divine revelation about divine things (ST 1a 1).

Thomas has more to say about the science of theology:

Holy teaching can borrow from other sciences, not from any need to beg from them, but for the greater clarification of the things it conveys. For it takes its principles directly from God through revelation, not from the other sciences. On that account it does not rely on them as they were in control, for their role is subsidiary and ancillary; so an architect makes use of tradesmen as a statesman employs soldiers. That it turns to them in this way is not from any lack or insufficiency within itself, but because our understanding is wanting; it is the more readily guided into the world above reason, set forth in holy teaching, through the world of natural reason from which the other sciences take their course (ST 1a 5).

Holy teaching, Scripture, special revelation, is directly from God. It can be clarified to our limited understanding by the help of other sciences such as logic, languages, history. But it is above reason, conveying the divine mysteries.

So sacred Scripture, which has no superior science over it, disputes the denial of its principles; it argues on the basis of those truths held by revelation which an opponent admits as when, debating with heretics, it appeals to received authoritative texts of Christian theology, and uses one article against those who reject another. If, however, an opponent believes nothing of what has been divinely revealed, then no way lies open for making the articles of faith reasonably credible; all that can be done is to solve the difficulties against faith he may bring up. For since faith rests on unfailing truth, and the contrary of truth cannot really be demonstrated, it is clear that alleged proofs against faith are not demonstrable, but charges that can be refuted (ST 1a 1.8).

Perhaps these words tell us about Thomas’s views on apologetics. If so they are very different from those of Oliphint. These words will be a surprise to those who hold to his views. The entire article ought to be weighed.

So, there is a scientia of Christian theology derived from Scripture. Then, in Question 2, there is the question “Whether the existence of God is self-evident?” Thomas’s answer is that God is evident, but not to us, and so that evidence has to be made to be self-evident to us by arguing from God’s effects as grounding God’s existence. This is a philosophical scientia: “From effects evident to us, therefore, we can demonstrate what in itself is not evident to us, namely that God exists.” And, as already mentioned, in that question Aquinas attempts to show this in detail, in five parallel arguments from effects, the Five Ways, that God exists. This is his natural or rational theology, for which he finds precedent in Paul’s positive remarks in Romans 1:20. So even his natural or rational theology is warranted by Scripture.

The fact that rational or natural theology begins with the existence of God while the articles of faith presuppose it may make it seem as if natural theology complements or completes revealed theology, and that it serves to put the articles of faith on a firmer footing. But to draw this conclusion is a temptation that must be resisted. It finds no warrant in what Aquinas said of each of them. The proofs and the development of articles of theology are two distinct, complementary activities. Nevertheless, they are in some way related, or connected, as we shall shortly see.

Consider these two extracts from another writing of Thomas.

A thing is . . . an object of belief not absolutely, but in some respect, when it does not exceed the capacity of all men, but only of some men. In this class are those things which we can know about God by means of a demonstration, as that God exists or is one and so no body and so forth.[3]

And this from later on in the ST:

The truths about God which St. Paul says we can know by our natural powers of reasoning—that God exists, for example,—are not numbered among the articles of faith, but are presupposed to them. For faith presupposes natural knowledge, just as grace does nature and all perfections that which they perfect. However, there is nothing to stop a man accepting on faith some truth which he personally cannot demonstrate, even if that truth in itself is such that demonstration could make it evident (ST 1a 2.2).

The articles of the faith are for everyone, not for those only with the necessary aptitude and intelligence to study demonstrative proofs for God’s existence at their leisure, etc. Special gifts are necessary to formulate and follow philosophical arguments such as the Five Ways. So Christian Theology is available to all persons, learned and unlearned alike, but in different, though overlapping ways.

That God exists is a precondition for faith, the Christian faith. It may seem from this that the results of one kind of knowledge form the foundation for another kind. Yet we are not to assume that every time Aquinas refers to the existence of God he has the proofs in mind, much less that reasonable proof is a precondition of faith or that such a proof leads to faith. In fact, the precise opposite of this is the case. If someone is not able to reason philosophically, they are nevertheless able to assent to the matters of the Christian articles by faith through grace.

There is need here to distinguish between Aquinas’s references to preambles, the praeambulae fidei and similar expressions, and his references to articles of faith and other similar expressions. It may seem that the words referring to preambles refer to preliminaries that are necessary to exercise faith, such that ‘God is one’ is not by itself an article of faith but what is preliminary to something being an article of faith. It is a presupposition of an article of faith that is, he thinks, demonstrable by reason by those who are appropriately gifted. Aquinas recognizes that proving that God exists requires ability, leisure, and aptitude to carry out such a demonstration. Other such demonstrable truths that depend on the proof of the existence of God are that God is truthful and that God reveals himself.

[T]he first principles of this science are the articles of faith, and faith is about God. Now the subject of a science’s first principles and of its entire development is identical, since the whole of a science is virtually contained in its principles (ST 1a 1.7).

So we learn, for example, that since adherence to the Christian faith is a matter of faith in the main articles of the Christian faith, it entails an end beyond the grasp of reason [quoting Isa. 64:4]. This faith is meritorious,[4] and has the quality of certitude. Certitude is the unreserved assent of the intellect. It may occur where demonstration has not been achieved. This is a matter that involves the will as well as the intellect, being not objectively but subjectively certain, and so of primary importance. “[D]ivine truths surpassing reason should be signified to us through divine revelation” (ST, 1a 1.1). By contrast, the “rational proofs” are attainable only by a few, who have the necessary gifts. But the place of reason in Christian theology operates within what is revealed.

Aquinas teaches that Christian theology argues from its premises, not to them. He says:

As the other sciences do not argue to prove their premises, but work from them to bring out other things in their field of inquiry, so this teaching does not argue to establish its premises, which are the articles of faith, but advances from them to make something known, as when St. Paul adduces the resurrection of Christ to prove the resurrection of us all (I. Cor. 15.12) (ST 1a 1.8).

Aquinas goes on to make clear that arguments for the articles of faith are held through revelation.

All the same Christian theology also uses human reasoning, not indeed to prove the faith, for that would take away from the merit of believing, but to make manifest some implications of its message. Since grace does not scrap nature but brings it to perfection, so also natural reason should assist faith as the natural loving bent of the will ministers to charity (ST 1a 1.8).

In considering Aquinas’s thought we are dealing with the pre-Reformation church. As far I can see he does not regard working on the proofs as similarly meritorious.

Argument from authority is the method most appropriate to this teaching [viz. the understanding of the articles of faith] in that its premises are held through revelation; consequently it has to accept the authority of those to whom revelation was made. Nor does this derogate from its dignity, for though weakest when based on what human beings have held, the argument from authority is most forcible when based on what God has disclosed (ST 1a 1.8.).

These various extracts and references underline the fact that the ST is a Christian work from the start and it assumes a Christian readership. It is taken as granted that this readership is familiar with and sympathetic to the theological articles. Such theology is drawn from the canonical Scriptures. From them have been derived articles of faith that may be accepted with certitude by which a person may have faith in the articles of the faith.

Sacred doctrine employs such [philosophical] authorities only in order to provide, as it were, extraneous arguments from probability. Its own proper authorities are those of canonical Scripture, and these it applied with convincing force (ST 1a, 1.8).

The entire section of Article 8 is enlightening for Aquinas’s approach to nature, and by implication, to rational theology.

It is almost as if the conduct of natural theology and of Christian theology take place in two distinct groups at arm’s length from each other. And in a way this is true. For the curriculum of teaching philosophy and theology was such that natural theology (following Aristotle) is part of philosophy, preliminary to the study of the articles of Christian theology that is based on the canonical Scriptures. These matters reflect the character of the education for would-be theologians who had philosophical education before the study of revealed theology. Natural theology was conducted under philosophical auspices. Revealed theology had its source in special revelation.

As if to underline this, Aquinas draws attention to the relation of each, and to the relative value of each to the other in later on passages such as: “By faith we hold to many truths about God that philosophers could not fathom, for example, the truths about his providence, omnipotence and sole right to adoration. All such points are included in the one article of faith ‘I believe in one God'” (ST 2a 2ae 1.8).

The following on the theological virtue of faith is very similar.

From divine effects we do not come to understand what the divine nature is in itself, so we do not know of him what he is. We know of him only as transcending all creatures . . . It is in this way that the word “God” signifies the divine nature: it is used to mean something that is above all that is, and that is the source of all things and is distinct from them all. This is how those that use it mean it to be used (ST 1a 13.8).

Aquinas’s opening words in the ST that we have been considering are very different from what they would have been had he believed that accepting the proofs are indispensable preliminaries to attending to Scripture.

Endnotes

[1] K. Scott Oliphint, Thomas Aquinas, Great Thinkers, foreword by Michael A. G. Haykin (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2017, 145pp.).

[2] References to the Summa Theologiae are by Part, Book, and Question, placed in the main text of this review. The translation used is that of the Dominicans, general editor, Thomas Gilby (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1963-70). It is also available in Kindle, and parts of it were reprinted in Image Books (1969), including the passages we shall cite.

[3] Thomas Aquinas, The Disputed Questions on Truth, Vol. 2, trans James V. McGlynn S.J. (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1953) 14.9. I have taken this and some other extracts of Aquinas from Arvin Vos, Aquinas, Calvin, and Contemporary Protestant Thought (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1985), 88.

[4] The presence here of the idea of personal merit, which came to be central to the opposition of the Reformation, reminds us of Thomas’s Roman Catholicism.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published at Helm’s Deep. The entire review is published in the Journal of IRBS Theological Seminary (2018): 163-93. It may be purchased at www.rbap.net.