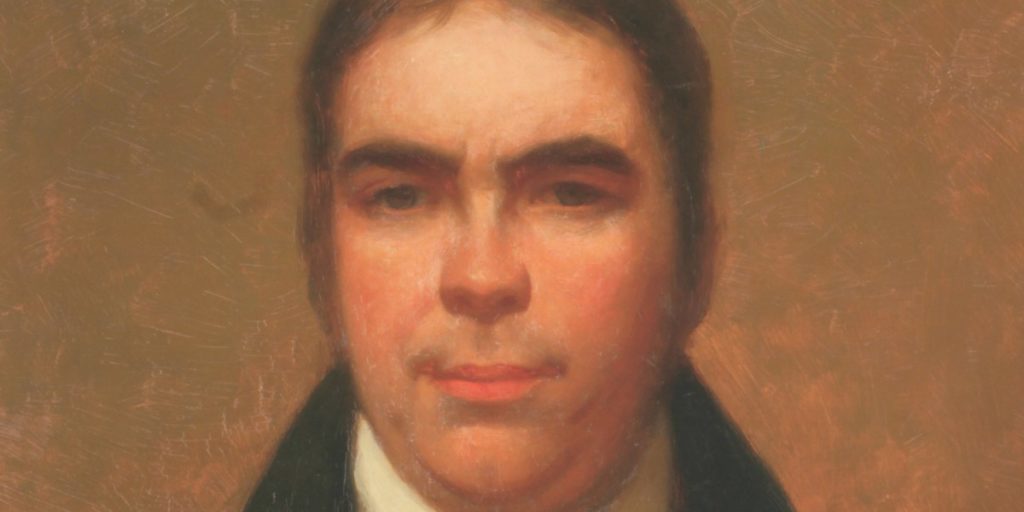

Why Pastors Should Engage Andrew Fuller

Near the beginning of the funeral sermon that John Ryland, Jr. (1753–1825) preached for Andrew Fuller in 1815, Ryland described Fuller as “perhaps the most judicious and able theological writer that ever belonged to our [i.e. the Calvinistic Baptist] denomination.” Although Fuller was Ryland’s closest friend and confidant, his judgment is by no means skewed. The importance of his theological achievements was noted during and after his life. The College of New Jersey (now Princeton [1798]) and Yale (1805) both awarded him a D.D., neither of which he accepted. Joseph Belcher, the editor of the final edition of Fuller’s collected works, believed that his works would “go down to posterity side by side with the immortal works of the elder president Edwards [i.e. Jonathan Edwards, Sr.],” while Charles Haddon Spurgeon once described Fuller as “the greatest theologian” of his century. And the Southern Baptist historian A. H. Newman said that “his influence on American Baptists” was “incalculable.” What contributed to these judgments? Why should pastors engage Andrew Fuller?

Fuller and the Advocacy of the Free Offer of the Gospel

Well, first of all, there is the fact that Fuller penned the definitive response to hyper-Calvinism that had crippled far too many of his fellow eighteenth-century Baptists in The Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation. A preliminary draft of this work was written by 1778. In what was roughly its final form it was completed by 1781. Two editions of the work were published in Fuller’s lifetime. The first edition, published in Northampton in 1785, was subtitled The Obligations of Men Fully to Credit, and Cordially to Approve, Whatever God Makes Known, Wherein is Considered the Nature of Faith in Christ, and the Duty of Those where the Gospel Comes in that Matter. The second edition, which appeared in 1801, was more simply subtitled The Duty of Sinners to Believe in Jesus Christ, a subtitle that well expressed the overall theme of the book. There were a few important differences between it and the second edition (1801), which Fuller freely admitted and which primarily related to the doctrine of particular redemption. The work’s major theme remained unaltered, however: “faith in Christ is the duty of all men who hear, or have opportunity to hear, the gospel.” This epoch-making book sought to be faithful to the central emphases of historic Calvinism while at the same time attempting to leave preachers with no alternative but to drive home to their hearers the universal obligations of repentance and faith. Fuller sought to be faithful to the central emphases of historic Calvinism while at the same time attempting to leave preachers with no alternative but to drive home to their hearers the universal obligations of repentance and faith. Click To Tweet

With regard to Fuller’s own ministry, the book was a key factor in determining the shape of that ministry in the years to come. For instance, it led directly to Fuller’s wholehearted involvement in the formation of the Baptist Missionary Society in October 1792 and the subsequent sending of the Society’s most famous missionary, William Carey (1761–1834), to India in 1793. Fuller also served as secretary of this society until his death in 1815. The work of the mission consumed an enormous amount of Fuller’s time as he regularly toured the country, representing the mission and raising funds. On average he was away from home three months of the year. Between 1798 and 1813, moreover, he made five lengthy trips to Scotland for the mission as well as undertaking journeys to Wales and Ireland (1804). He also carried on an extensive correspondence on the mission’s behalf. Fuller was thus vitally involved in and committed to the globalization of the Christian Faith.

Fuller’s commitment to the Baptist Missionary Society was not only rooted in his missionary theology but also in his deep friendship with Carey. Fuller later compared the sending of Carey to India as the lowering of him into a deep gold-mine. Fuller and his close friends, Sutcliff and Ryland, had pledged themselves to “hold the ropes” as long as Carey lived. No wonder, Carey would say of Fuller when he heard of his death in 1815: “I loved him.”

Fuller the Apologist for Christian Orthodoxy

His demolition of hyper-Calvinism revealed Fuller to be an indefatigable and fearless Baptist theologian and minister, characteristics that became manifest in other vital areas of theological debate. In 1793 he issued an extensive refutation of the Socinianism of Joseph Priestley (1733–1804)—The Calvinistic and Socinian Systems examined and Compared, as to their Moral Tendency. Due to the vigorous campaigning of Priestley, Socinianism, which denied the Trinity and the deity of Christ, had become the leading form of heterodoxy within English Dissent in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Fuller’s rebuttal of Socinianism well displays the Christocentric nature of eighteenth-century Evangelical thought. Fuller ably showed that the early Church made the divine dignity and glory of Christ’s person “their darling theme.”

In 1800 Fuller published The Gospel Its Own Witness, the definitive eighteenth-century Baptist response to Deism, in particular, that of the popularizer Thomas Paine (1737–1809), one of the most versatile authors of the eighteenth century. This work was one of the most popular of Fuller’s books, going through three editions by 1802 and being reprinted a number of times in the next thirty years. William Wilberforce (1759–1833), who admired Fuller as a theologian and who once graphically described him as “the very picture of a blacksmith,” considered it to be the most important of all of Fuller’s writings. The work has two parts. In the first, Fuller compares and contrasts the moral effects of Christianity with those of Deism. The second part of the book aims to demonstrate the divine origin of Christianity from the general consistency of the Scriptures.

Yet another vital controversy in which Fuller engaged was that with the Sandemanians, the followers of Robert Sandeman (1718–1771), who distinguished themselves from other eighteenth-century Evangelicals by a predominantly intellectualist view of faith. They became known for their cardinal theological tenet that saving faith is “bare belief of the bare truth.” In a genuine desire to exalt the utter freeness of God’s salvation, Sandeman had sought to remove any vestige of human reasoning, willing or desiring in the matter of saving faith. In his Strictures on Sandemanianism (1810) Fuller makes a couple of telling points. First, if faith does concern only the mind, then there would be no way to distinguish genuine Christianity from nominal Christianity. A nominal Christian mentally assents to the truths of Christianity, but those truths do not grip the heart and re-orient his or her affections. Then, knowledge of Christ is a distinct type of knowledge. Knowing him, for instance, involves far more than knowing certain things about him, such as the fact of his virgin birth or the details of his crucifixion. It involves a desire for fellowship with him and a delight in his presence.

Fuller the Pastor

Alongside his apologetic works, Fuller exercised a significant pastoral ministry at Kettering. During his thirty-three years at Kettering, from 1782 to 1815, the membership of the church more than doubled (from 88 to 174) and the number of “hearers” was often over a thousand, necessitating several additions to the church building. A perusal of his vast correspondence—today housed in the Angus Library, Regent’s Park College, the University of Oxford—reveals Fuller to have been first and foremost a pastor. And though he did not always succeed, he constantly sought to ensure that his many other responsibilities did not encroach upon those related to the pastorate.

One other of Fuller’s literary works deserves mention. His Memoirs of the Rev. Samuel Pearce (1800) recount the life of his close friend, Samuel Pearce (1766–1799) of Birmingham. In some ways modeled after Jonathan Edwards’ life of David Brainerd, it recounted the life of one whom Fuller regarded as a model of Evangelical spirituality. Fuller showed that Pearce’s character was first and foremost one that was controlled by “holy love,” which Fuller was rightly convinced lay at the heart of true spirituality. Through the medium of Fuller’s book, Pearce’s extraordinary passion for Christ—which led to his being labeled the “seraphic Pearce” by contemporaries—and his zeal for missions had a powerful impact on his generation and subsequent ones down to the present day.