Why Pastors Should Engage B.B. Warfield

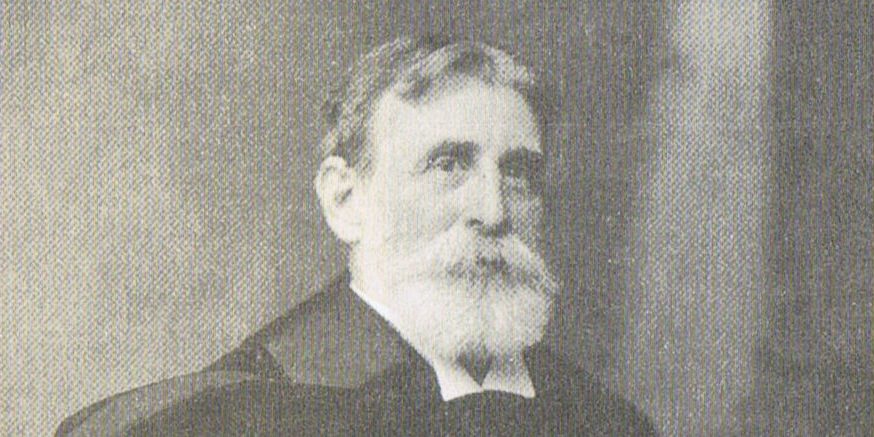

My first exposure to Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield (1851-1921) was in a Christian bookstore while I was in college. Of course I immediately recognized that this was a man I could learn from, and my interest was kindled from the very first. Throughout the coming decades of pastoral ministry, I have tried to read widely, but my Warfield reading remained. As my acquaintance with him grew, I was able at many points to go back to him and shore up my understanding of this or that passage or topic that by then I knew he had addressed, and at each turn my appreciation for him increased. I am Baptist and premillennial by what I hope is informed conviction, and these (ecclesiology and eschatology) remain my leading areas of difference with the great Princetonian. And I don’t share his commitment to traditional covenant theology, a matter that does not crop up in his writings very often – surprisingly, given his commitment to it. But pervasively Warfield’s work has proved deeply enriching to me and to my ministry, and here I mention four leading features of his work that I hope could rub off on me in some degree.

Theological Learning

First and most obviously, is Warfield’s breadth and depth of learning on all matters touching biblical and theological studies. He was widely recognized on this score in his own day, and he remains a model of theological learning. Warfield’s career was during the hey day of old liberalism, and he was eager to confront attacks from all quarters. And with each engagement he clearly “owned” the discussion. He seemed as comfortable addressing matters of theology (the department of study that marked his career), Old Testament (an area of his early interest), New Testament (the department he occupied in his first years as a seminary professor), apologetics, or historical and critical studies, he came to the table with an imposing (and for those on the other side, intimidating) grasp of the subject at hand. This depth and breadth of theological learning is in large measure what made him the powerhouse theologian that he was. Opponents feared his pen, and the faithful – then and still today – are grateful to God for it.

To be compelling, Biblical exposition as well as theological arguments must have a cohesiveness to them. They must be rightly and broadly informed. They must “hang together” with related issues and ideas of all kinds as well as with countless related biblical statements and concepts. The work of the preacher is never done on this score, and Warfield is a reminder that in order to “make full proof of our ministries” we must, among so many other things, spend much time in thoughtful study and reading – learning from the Scriptures and learning from others who have learned the Scriptures ahead of us.

Exegetical Precision

This depth and breadth of learning inevitably marked Warfield’s preaching, but it was not its only mark. Warfield’s preaching – and all his writing – was marked also by exegetical precision. This was the greatest strength of his theological endeavors. He handled Scripture responsibly. Yes, there are places where I think he missed it – his treatment of Revelation 20, for example, he admittedly struggles to make the passage “work” within his postmillennial commitments. And there are some places where his exposition would be enriched by a grasp of the “Biblical Theology” of his later colleague, Geerhardus Vos. But throughout my ministry as I read Warfield I was struck again and again by his close eye to the biblical text. He was supremely the exegete – pointing to the text, laying it open, and demonstrating “this is what it demands.” Share on X

When I was first coming of age in theological studies I heard often that the strength of Hodge’s Systematic Theology was just this – careful exegesis. And so I was a bit surprised back then to read Warfield say of his revered and beloved former professor that this was in fact his weakness. My impression then was that this remark says as much about Warfield as it does about Hodge. In any case, no one can read Warfield without noticing that his handling of the Scriptures has a precision about it that is just compelling. He was not a theologian who did exegesis but an exegete who did theology. This is what ought to mark the preaching of every minister of the Word, and reading Warfield teaches us by example how to let the text speak.

Devotion to Christ & Clear Gospel-Centeredness

But all this is just the backdrop of what made Warfield so attractive to me. There are two more aspects of his work that get to the “soul” of Warfield, and I will mention them here together: his gospel-centeredness and his passionate heart for Christ. Warfield’s gospel-centeredness was no mere clichéd fad – he was gospel-centered long before Don Carson and Tim Keller made it cool. He understood Christianity, simply, in gospel terms. Christianity is at its core a redemptive religion. Indeed, this is its very meaning – redemption – and apart from redemption Christianity has no reason to exist. This is how Warfield understood it. He insisted on it:

The message of Christianity concerns, not ‘the values of human life,’ but the grace of the saving God in Christ Jesus. And in proportion as the grace of the saving God in Christ Jesus is obscured or passes into the background, in that proportion does Christianity slip from our grasp. Christianity is summed up in the phrase: ‘God was in Christ, reconciling the world with himself.’ Where this great confession is contradicted or neglected, there is no Christianity.”

Moreover, this was for Warfield no mere academic observation. It was for him the value of Christianity personally. He was a massively learned theologian, highly respected even internationally. But in his own heart he saw himself as a guilty sinner rescued only by the sacrifice of Christ. “Redeemer” was the title for Christ that above all others stirred his heart, he confessed. And throughout his writing there pulses this sense of fervent adoration for and utter, whole-souled dependence on the Lord Jesus. Even in his most academic and polemic works defending the person and work of Christ Warfield cannot refer to our Lord but with worshipful and affectionate tones. It is here we get to the heart of Warfield, and it is here that our engagement with him would most profitably affect us: in all we learn and in all we preach and do, may there be an eye for the gospel and a heart that beats hot for our great Redeemer.

I have learned much from many men, and I have other theologians who are in my “favorite” category. But I have not known any who model better the “head and heart” that ought to mark every Christian minister.[i] It was in fact the ideal, the stated goal of Old Princeton since its founding. Reading Warfield widely and deeply you can’t help but catch that spirit.

This is why pastors should engage B.B. Warfield.

Endnotes

[i] I demonstrate this joyfully and at some length in chapter 13 of my The Theology of B.B. Warfield, as well as in my Warfield on the Christian Life.