Unconditional Election: Why Some Believe and Others Remain in Their Sin

The new issue of  Credo Magazine focuses on Dort at 400. The following is an excerpt from Cornelius Venema’s article, “Unconditional Election: Why Some Believe and Others Remain in Their Sin.” Cornelis Venema (PhD, Princeton Theological Seminary) is President and Professor of Doctrinal Studies at Mid-America Reformed Seminary. He is the author of numerous books including But for the Grace of God: An Exposition of the Canons of Dort, Chosen in Christ: Revisiting the Contours of Predestination, The Promise of the Future, The Gospel of Free Acceptance in Christ: An Assessment of the Reformation and ‘New Perspectives’ on Paul, and Christ and Covenant Theology: Essays on Election, Republication, and the Covenants.

Credo Magazine focuses on Dort at 400. The following is an excerpt from Cornelius Venema’s article, “Unconditional Election: Why Some Believe and Others Remain in Their Sin.” Cornelis Venema (PhD, Princeton Theological Seminary) is President and Professor of Doctrinal Studies at Mid-America Reformed Seminary. He is the author of numerous books including But for the Grace of God: An Exposition of the Canons of Dort, Chosen in Christ: Revisiting the Contours of Predestination, The Promise of the Future, The Gospel of Free Acceptance in Christ: An Assessment of the Reformation and ‘New Perspectives’ on Paul, and Christ and Covenant Theology: Essays on Election, Republication, and the Covenants.

Even as He chose us in Him [Christ] before the foundation of the world, that we should be holy and blameless before Him. In love He predestined us for adoption as sons through Jesus Christ, according to the purpose of His will, to the praise of His glorious grace, with which He has blessed us in the Beloved. (Eph. 1:4-6)

The importance of the teaching of unconditional election, the first main point of doctrine affirmed in the Canons of Dort, cannot be overstated. As J. I. Packer once put it, the doctrine of election preserves the simple gospel truth that “God saves sinners.” Sinners do not save themselves. Only God saves, and he does so out of his undeserved love and free decision to grant his people salvation in Christ—and that “before the foundation of the world”! By affirming this, the Synod of Dort preserved the biblical teaching that salvation is by grace alone. And at the same time, the Synod of Dort provided a sure footing for confidence in God’s invincible grace in Christ.

The Arminian Doctrine of Conditional Predestination

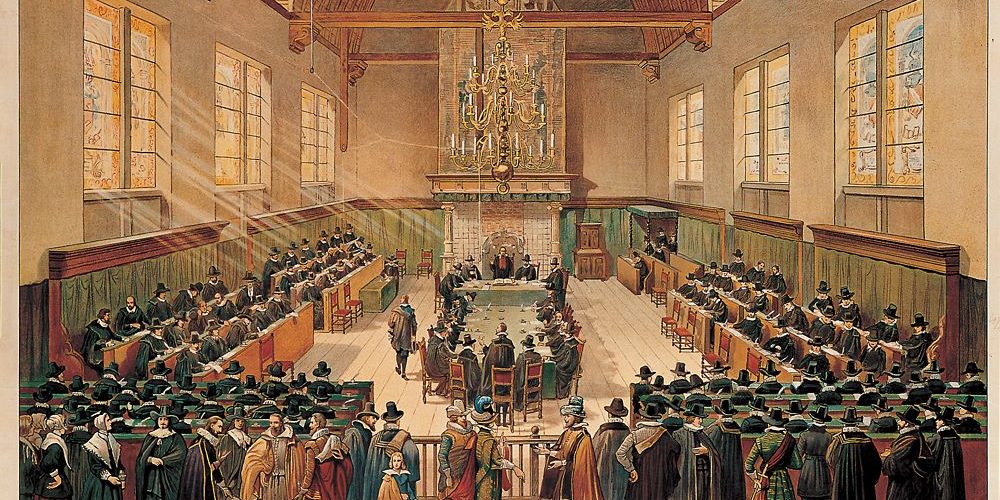

To appreciate the Canons’ teaching on unconditional election, it is important to remember that they were articulated in a specific historical context. The Synod of Dort was convened to address the controversy that broke out in the Reformed churches of the Netherlands in response to the teaching of James Arminius (1560-1609) and his followers, the “Remonstrants.”[1] Arminius, a brilliant student of Theodore Beza, Calvin’s successor in Geneva, initiated the controversy during his tenure as a pastor of the Reformed church in Amsterdam and subsequently as a professor of theology at the University of Leiden.

Shortly before his death in 1609, Arminus summarized his teaching on election in two important works, his Public Disputations and Declaration of Sentiments.[2] In these works, Arminius expressed serious objections to the Reformed view of unconditional election as it was set forth in Article 16 of the Belgic Confession.[3] According to this Article, the salvation of those whom God mercifully elects in Christ depends entirely upon God’s gracious purpose of election, and not upon any human merit or achievement. Only God saves, and he does so out of his undeserved love and free decision to grant his people salvation in Christ—and that “before the foundation of the world”! Click To Tweet

Contrary to the consensus of the Reformed churches, Arminius argued for what is most aptly described as a doctrine of “conditional election.” In his Declaration of Sentiments, Arminius summarized his teaching by distinguishing four decrees within God’s eternal mind and will. Though Arminius formulated these four decrees in a highly “scholastic” and theological manner, his position can be simply stated in four points:[4]

First, God eternally and absolutely wills to save all fallen sinners, and therefore has decreed to appoint his Son Jesus Christ as the Mediator and Savior of all who are lost. The first and foundational decree of God expresses his universal and gracious intention to save all fallen sinners without exception upon the basis of Christ’s atoning work.

Second, God eternally and absolutely wills to receive into favor all fallen sinners who repent and believe, and to leave under his wrath all who remain impenitent and unbelieving. Though God eternally and absolutely wills the salvation of all, he also wills to save only those who choose to believe and persevere in believing and to damn those who choose to remain in their sin and unbelief.

Third, God eternally wills to appoint the means by which fallen sinners are able to come to faith and repentance. These means include the ministry of the Holy Spirit, who uses the Word and sacraments to invite fallen sinners to respond to the gospel in the way of faith and repentance. The actual salvation of fallen sinners depends upon their willingness to meet the “conditions” of the gospel invitation.

And fourth, God eternally decrees to save those particular persons whom he foreknows will believe and persevere in believing in response to the gospel; and he eternally decrees to damn those whom he foreknows will choose not to believe and persevere in believing. The election and actual salvation of some fallen sinners rests upon God’s foreknowledge of their free choice to believe and to persevere in faith.

Arminius’ fourth point clearly draws out the implications of the preceding three points for the doctrine of election. Though God wills absolutely and antecedently to save all fallen sinners, he wills relatively and consequently to save only those particular persons whom he foreknows would believe and to damn those whom he foreknows would not.[5]

The basis for God’s decree to save and damn “certain particular persons” is his foreknowledge of the way these persons freely (independently) choose to respond to the gospel call. The ultimate condition and ground for the actual salvation of sinners rests upon the free choice of some to believe and to persevere in faith.

On the one hand, God’s universal will and intention to save all fallen sinners is frustrated or thwarted in the case of all those who persistently refuse to respond in faith to the invitation of the gospel. And on the other hand, God’s decision to save the elect is dependent upon, or in consequence of, their choice to believe and to persevere in doing so.[6]

Read Cornelius Venema’s entire article in the new issue of Credo Magazine: Dort at 400.

Endnotes

[1] Arminius’ followers are commonly designated “Remonstrants” because they presented their views in the form of a Remonstrance or formal petition to the civil authorities in 1610. This Remonstrance presented the Arminian view in the form of five opinions. The five main points of doctrine articulated in the Canons are, accordingly, a reply to each of these opinions. For a helpful treatment of the historical background to and resolution of the controversy at the Synod of Dort, including a translation of this Remonstrance, see Crisis in the Reformed Churches: Essays in Commemoration of the Great Synod of Dort 1618-1619, P. Y. De Jong, ed. (2nd ed.; Grandville, MI: Reformed Fellowship, Inc., 1968 [2008]).

[2] Public Disputations, in The Works of James Arminius [hereafter: WJA], trans. James Nichols and William Nichols (London: 1825, 1828, 1875; reprint, Grand Rapids: Baker, 1986), 2:80-312; and Declaration of Sentiments of Arminius, delivered before the States of Holland, in WJA 2:580-732.

[3] Article 16 declares: “We believe that, all the posterity of Adam being thus fallen into perdition and ruin by the sin of our first parents, God then did manifest Himself such as He is; that is to say, merciful and just: merciful, since He delivers and preserves from this perdition all whom He in His eternal and unchangeable counsel of mere goodness has elected in Christ Jesus our Lord, without any respect to their works; just, in leaving others in the fall and perdition wherein they have involved themselves.”

[4] See Declaration of Sentiments, in WJA, 1:653-54, for Arminius’ more scholastic statement of these four points.

[5] Richard A. Muller, “Grace, Election, and Contingent Choice: Arminius’ Gambit and the Reformed Response,” in The Grace of God, the Bondage of the Will, ed. Thomas R. Schreiner and Bruce A. Ware (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1995), 274: “According to this doctrine, God genuinely wills that which he knows will never happen, indeed, what he wills not to bring about!”

[6] Muller, “Grace, Election, and Contingent Choice,” 266: “… if the salvation of human beings rests on divine foreknowledge, the human being is clearly regarded as the first and effective agent in human action.”