Why Pastors Should Engage Gregory of Nazianzus

The Council of Nicaea convened in 325 to deal with Arius and his heresy concerning the relationship of Jesus to the Father. Arius proclaimed that the Son was not eternal and thus not a part of the Trinity in His very being. Arius stated that the Son existed as a creation of the Father. Arius’ heresy caused Christianity to face a universal, ecclesiastical crisis: Who is Jesus in relation to the Father? Is the Logos eternal? Depending on how Christians answered, Christianity was in danger of losing its foundation from a threat within the parameters of orthodoxy.

The Council heard Arius, rejected his theology as deviant, and adopted the Nicene Creed, which became the official doctrine of the universal Church. The Nicene Creed established that the Son was the same substance (homoousia) as the Father, defeating Arianism. Yet, the Arians did not take defeat well and managed to live on. Thirty years later, in the mid-350s, the Heterousians revived Arianism. These people believed that the Son was unlike the Father in His substance and denied the Trinity, stating that there was only a monarchy. They gained solid position in the universal Church and ruled Christendom in the 350s and throughout most of the 360s. During this era, Gregory of Nazianzus performed his ministry.

Second Generation Minister

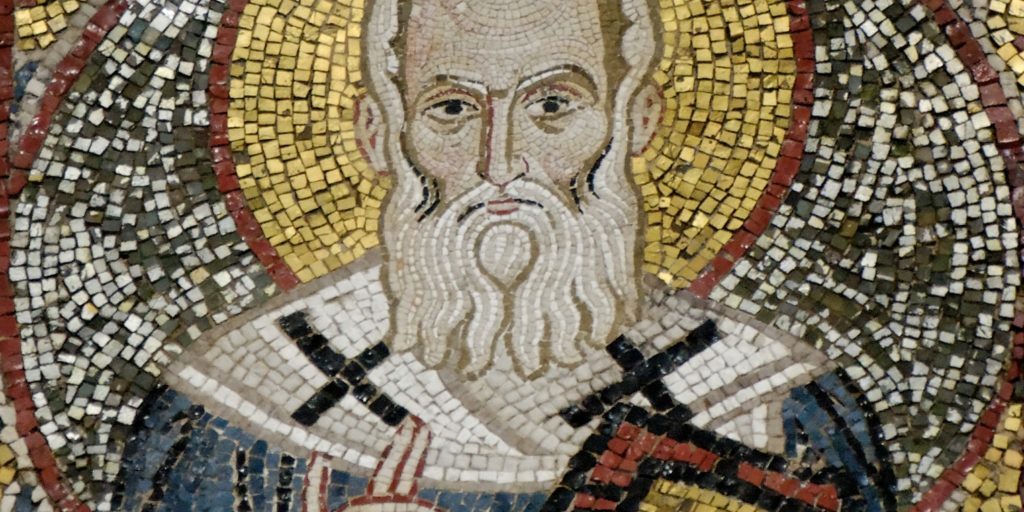

Gregory of Nazianzus, also known as Gregory the Theologian, was born in 329 at Nazianzus in Cappadocia (modern day Turkey). His father, also named Gregory, served as a bishop of Nazianzus. His mother, Nonna, taught him the Scriptures and made certain that he received an extensive education. He studied rhetoric with his friend Basil, later named Basil the Great, and Julian, who became an emperor known as Julian the Apostate. At the completion of his studies, Gregory taught rhetoric, philosophy, and literature. In 358, Gregory returned to Cappadocia. Gregory’s father baptized him when he was thirty-three. His father, as bishop of Nazianzus, had Arian tendencies and even signed a statement of faith that was, at best, ambiguous in meaning concerning the Trinity.

Gregory soon left Nazianzus to be with his friend Basil at Pontus. After a few years, Gregory’s brother died, which compelled him to return to help his father in the work of the church. His father’s church was in turmoil because of the Arian heresy. Gregory began to convince his father of the deviant theological nature of Arianism. Gregory substantially impacted his father, as the elder Gregory did eventually embrace the Nicene position.

During this same time, Basil had been made a bishop of Caesarea. Basil’s rival, the Arian Bishop Anthimus, wanted to divide Cappadocia into two provinces. This prompted Basil to make Gregory a bishop of Sasima, which was a strategic, small town between Caesarea and Tyana. Gregory never accepted the role, as his father began to experience declining health. Gregory returned to Nazianzos and assumed more responsibility for the church. After his father’s death, Gregory guided the flock until 374.

The ecclesiastical world was subject to the political world of emperors. When Patriarch Valentus of Constantinople died, a council of bishops invited Gregory to help at the church at Constantinople because heretical Arian theology infiltrated the church. Gregory’s task was substantial, as the Arians were members. Over time and with consistent preaching, Gregory slowly began to see an increase in orthodox believers against seemingly impossible odds and circumstances. For example, in April 379, an angry mob of Arian heretics interrupted a baptismal service and threw stones at the Orthodox priest, killing one bishop and wounding Gregory. Yet, Gregory’s determination to persist through the adversity allowed him to realize victory in Nazianzus. The following year, in 380, Gregory was consecrated as Bishop of Constantinople.

Gregory served at Constantinople for a couple of years then retired at Nazianzus. During the next six years, he wrote poetry. Gregory died in 390 after a long and fruitful ministry.

Gregory’s Orations

Gregory had a unique gift: He was a writer. His impact during his own time and ours is one of sheer brilliance. Even though he made many contributions to Christianity, his five sermons, known as The Five Theological Orations, stand out as his “magnum opus.” Gregory addresses the themes of the qualifications of theologians, the ability to theologize, and the topics of God and the Trinity. Basically, Gregory states that only those who are pure in soul and body, as being selfless in heart, may have the confidence to successfully contemplate God’s nature. If the One was from the beginning, then the Three were so too. Share on X

This seems to be a reference to the Arians who are less than pure in heart and, as a consequence, have denied the Son’s divine nature. For Gregory, the Trinity is at the heart of the Christian faith. Gregory’s Fifth Oration proves beneficial to understanding the Trinity. Gregory, addressing the Arian axiom, “There was a time when the Son did not exist,” counters this false claim by writing, “If ever there was a time when the Father was not, then there was a time when the Son was not. If ever there was a time when the Son was not, then there was a time when the Spirit was not. If the One was from the beginning, then the Three were so too,” (Oration 5. 4).

Building on the difference between the Son and the Spirit, Gregory uses the word “procession,” which is found in the Greek text of John 15:26. Gregory’s exegesis moves Trinitarian thought to a different level than Basil the Great. Gregory states, “The Holy Ghost, which proceeds from the Father; Who, inasmuch as He proceeds from That Source, is no Creature; and inasmuch as He is not Begotten is no Son; and inasmuch as He is between the Unbegotten and the Begotten is God,” (Oration 5.8). The Spirit is not the Son because the Son is begotten, whereas, the Spirit “proceeds from” the Father. The Holy Spirit’s procession precludes him from being classified as a mere creature. The Holy Spirit is not the Son, as He is different from the Unbegotten (Father) and the Begotten (Son). In fact, the Holy Spirit stands “between” them (Oration 5.8), indicating distinct persons in their unity. Gregory refined the relationship of the Trinity by focusing upon the procession of the Spirit. Gregory earned the title of “Gregory the Theologian” from The Five Theological Orations, which is a must-read, preferably the edition in the Popular Patristic Series by St. Vladimir’s Press as it is an easier English translation.

Gregory’s Christology is equally impressive. He defended the position that the Logos (Jesus Christ) was fully human and fully God, which struck at the heart of Appolinarius, who advocated that Jesus had a divine mind (the Logos) in a human body. Gregory’s stunning reply has become a classic phrase in Christianity: “What is not assumed is not saved.” This phrase set the tone and anticipated the Council of Chalcedon in 451.

Legacy

Gregory deserves his legacy. Rufinus translated Gregory’s writings, particularly his Orations, from Greek to Latin. Gregory’s writings circulated throughout the empire, influencing Christian thought. By 431, the Council of Ephesus quoted Gregory as authoritative. By 451, the Council of Constantinople designated Gregory as a “theologian.” He is a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church and considered a defender of the Faith. Gregory definitely influenced the Second Ecumenical Council of Constantinople in 381, which finally considered Arianism as unorthodox.