The Blessed and Only God: Part Four

Paul’s doctrine of God in 1 Timothy is profoundly high and profoundly deep. The Lord is high and lifted up, inhabiting eternity; yet also near, dwelling with the lowly and contrite in spirit. He is infinitely transcendent: immortal, invisible, the only God, dwelling in unapproachable light. But he is also intimately near in the person of Jesus Christ: coming into the world to save sinners, a mediator between God and men. These are facts about the true God that Paul lays out for us. But they are facts that demand further explanation. Why would such a God who dwells in eternal peace draw near to us in our brokenness and mess in the first place? If God is eternally content and happy in himself, why create anything? Why redeem anything? Why have any concern or interest in anything outside of himself?

The Blessed God, Three in One

To begin an answer to that “why” question, we have to back up to address a “how” question; How exactly do we connect God’s transcendence with his nearness. I said in my previous posts that it is because God is infinitely above us that he is able to draw so closely to us. There is nothing built into creation that would hinder such a God from drawing near. But the way Paul bridges that gap in his letter is not quite as straightforward as that.

We’ve seen that Paul clearly identifies the person we meet in the face of Jesus Christ with the King of the Ages, the blessed and only sovereign. Yet, we have to admit that Paul also at times distinguishes the two; or the very least, he complicates the relationship between Jesus the Man and God the Almighty. They are one and the same, and yet different. So, in Paul’s opening greeting to Timothy, he talks about God the Father and Jesus our Lord [read 1 Tim. 1:1-2]. This is a very typical way for Paul to start off his letters. He says the same thing, basically, in 2 Tim. 1:1-2 [read]. Clearly, a distinction is being made. Jesus is not the Father; we shouldn’t confuse the two. Later on, in 2:5 Paul writes those famous lines, “there is one God, and one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus.” I mentioned before how this passage does assume a certain unity between the one God and the one mediator; but there is also a distinction. There is a distinction being drawn between the mediator who carries us and the God we are carried to. In 1 Tim. 6:13, Paul again speaks of two different persons, “I charge you in the presence of God, who gives life to all things, and of Christ Jesus, who in his testimony before Pontius Pilate made the good confession.” Paul speaks of God and Jesus Christ; not only the God who simply is Jesus Christ.

And yet, as I’ve pointed out already, Paul also clearly identifies God with Jesus in other places. It is Jesus who is the subject of Paul’s rich, exalted doxologies. It is Jesus who is the King of Ages, immortal, invisible, unapproachable. Is Jesus God or is he someone alongside God? Paul is just as comfortable speaking of God and Jesus Christ, as he is talking about the God who is found in Jesus Christ. Jesus is the blessed Lord, but he is not the blessed Father.

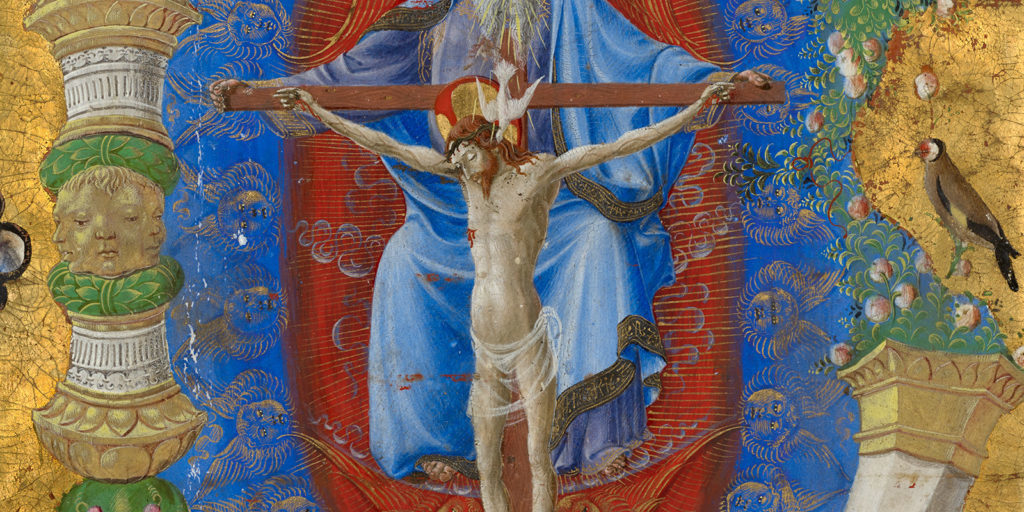

This strange moving back and forth between identifying Jesus with God and distinguishing Jesus from the Father is part of the dance we see in the rest of the NT. There is perhaps no better place to see this dance then in John 1:1, “in the beginning was the Word, the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” There it is, as clear as mud. The Word stands alongside God, and the Word stands as God. Both are somehow true. The way that Christians have come to understand and explain this NT behavior is one of the most precious treasures of the church: the doctrine of the Trinity. You may never find that word in the Bible, but you certainly find what it describes. The picture of God in the NT, when all the data is in, is that He is simultaneously three and one; Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. In the words of the Nicene Creed, God is three persons in one divine essence, one divine nature.

Now a full exploration of the doctrine of the Trinity is way beyond our reach here. It will even be beyond our reach given countless mornings in eternity. All I want to show you now is that Paul’s doctrine of God assumes something like the Trinity in the way he talks about Jesus and God; and that God’s triune nature is at the root of God’s divine blessedness and his divine mission to the world. I think I’ve already proved that first point. We find Paul both identifying and distinguishing Jesus from God in his letter. There is a dance between unity and difference. It’s the second point that should concern us now. God’s triune nature is at the root of God’s divine blessedness and his divine mission to the world. Click To Tweet

Invisible and Immortal

As I’ve said, in the midst of all Paul’s negative terms to describe God—he is invisible, he is immortal, he stands alone, he is unapproachable—stands this one positive term: blessed. That describes God’s state of supreme happiness and joy, utter contentment and peace. It’s the happiness of a Being whose life, existence, purpose, and meaning is independent of anything around him. He needs nothing and no one; but rather gives all things to everyone else.

Yet once we take into consideration Paul’s complex picture of Jesus and God, we suddenly realize that God’s blessedness means more than his freedom from everything around him. God is blessed not just because he’s content without everything else; he is blessed because he’s content with himself. Within the blessed Trinity, there is an eternal conversation that transcends anything we can understand or imagine. God stands alone, but he is never really alone. God has never been silent, he has been eternally talking and communicating; sharing life between Father, Son, and Spirit—“the word was with God, and the word was God.” There’s an outgoing nature to God, a ceaseless overflow of praise and love within God. The ultimate explanation for this not that he always has a world to love, but always has a Son to love in the bond of the Spirit.

If this were not true, God’s transcendence would be a lonely one. He would be alone with no one he could truly talk to or connect with. That’s rather trite language, but its language we understand. If it was “not good” for Adam to be alone in the garden, how much less God himself before there was a garden or universe to be in? God’s transcendence would not be a source of blessedness, but of loneliness; not restfulness, but restlessness. Creating or having a world would become a necessity for God’s happiness and blessedness. Its for this reason that most religions and philosophies argue that the world is just as eternal as God is; because God needs something eternal to keep him company.

But the world is poor company for God, with all our sins, brokenness, ignorance, and finitude. In the Christian faith, God has company with someone he can praise and enjoy with undiluted, reckless abandon. Jesus, praying that we would enjoy what the Father has eternally rejoiced in, says in John 17:24—truly one of the deepest and exciting verses in the Bible—“Father, I desire that they also, whom you have given me, may be with me where I am, to see my glory that you have given me because you loved me before the foundation of the world.”

It’s at this point now, that we can answer the “why” question. Why would an infinitely transcendent, eternally content God create anything at all? Why have any concern or interest in anything outside himself? God certainly didn’t need to create the world. He certainly doesn’t have to redeem it. But he does. How and why? The answer to both is the Trinity. Creation is not a reluctant act of God, its not an accident, its not an unfortunate necessity. Creation is a free gift, a gift from the Father to the Son. The universe is the ultimate inheritance of the ultimate firstborn Son. The world is the coat of many colors, teeming with life that the Father provides to bedeck and glorify his Son, to honor and display the majesty of his Son.

As we are told in John 5:22-23, “The Father judges no one, but has given all judgment to the Son, that all may honor the Son, just as they honor the Father.” The Father has placed the mantle, the coat of the world upon the shoulders of his Son, that he might fill all things; that we would rely on him, hang on his every word, rest in his every movement. It’s a coat that, beyond all belief, also has woven within in it the red threads of bloody sacrifice. There is no pressure point where the Son is better seen as the perfect Son and Mediator he is than when he is bearing the sins of the world across his frail, mighty shoulders.

*This is part two of a four part series on the Doctrine of God in 1 Timothy. See part one here, part two here, and part three here.