Not by Faith Alone? An Analysis of the Roman Catholic Doctrine of Justification from Trent to the Joint Declaration

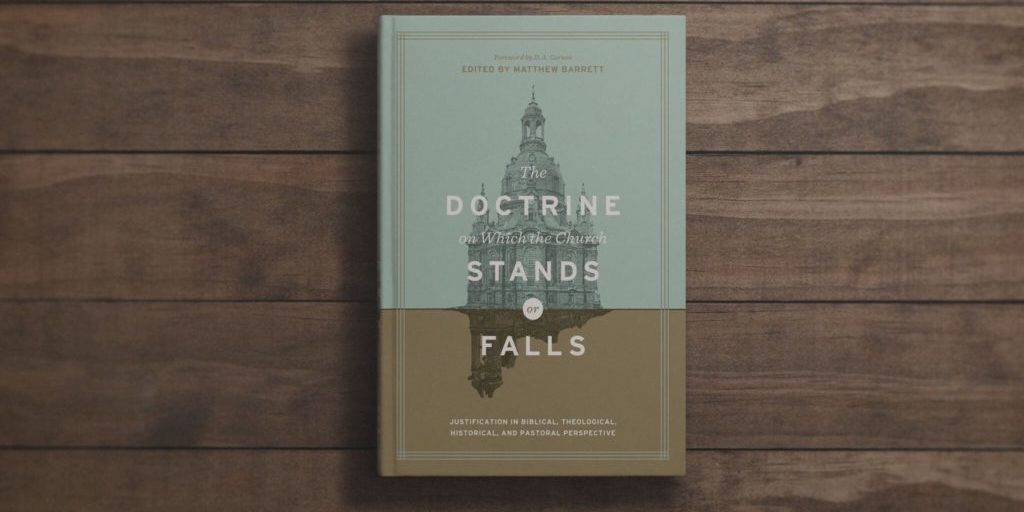

Matthew Barrett, executive editor of Credo Magazine, has edited a new book with Crossway titled, The Doctrine on Which the Church Stands or Falls: Justification in Biblical, Theological, Historical, and Pastoral Perspective. Many factors contributed to the Protestant Reformation, but one of the most significant was the debate over the doctrine of justification by faith alone. In fact, Martin Luther argued that justification is the doctrine on which the church stands or falls. This comprehensive volume of 26 essays from a host of scholars explores the doctrine of justification from the lenses of history, the Bible, theology, and pastoral practice—revealing the enduring significance of this pillar of Protestant theology.

Matthew Barrett, executive editor of Credo Magazine, has edited a new book with Crossway titled, The Doctrine on Which the Church Stands or Falls: Justification in Biblical, Theological, Historical, and Pastoral Perspective. Many factors contributed to the Protestant Reformation, but one of the most significant was the debate over the doctrine of justification by faith alone. In fact, Martin Luther argued that justification is the doctrine on which the church stands or falls. This comprehensive volume of 26 essays from a host of scholars explores the doctrine of justification from the lenses of history, the Bible, theology, and pastoral practice—revealing the enduring significance of this pillar of Protestant theology.

Today we are highlighting Leonardo De Chirico’s chapter “Not by Faith Alone?” Here is an excerpt to get you started:

Justification by faith was the matter of the Reformation five hundred years ago, but does it matter in the same way in the present-day ecumenical climate?[1] In responding to the Protestant account of justification, the Council of Trent (1545–1563) understood it inside a synergistic dynamic of the process of salvation. This understanding of grace appears in an updated form in the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification (JDDJ), signed in 1999 by the Roman Catholic Church and the Lutheran World Federation. The JDDJ is a clear exercise in an increased “catholicity” (i.e., the ability to absorb ideas without changing the core) on the part of Rome, which has not become more evangelical in the biblical sense.

Justification by faith alone has been a cause of rupture between Protestantism and the church of Rome since the sixteenth century, and this is an unchangeable fact with important theological and symbolic significance. The present-day status quaestionis of the debate is a contested issue. Roughly speaking, there are two ways of coming to terms with its contemporary relevance. According to mainstream ecumenical theology, “the doctrine of justification should not be, today, an element of division between churches.”[2] This does not mean that all differences and distinctions have been overcome, but it does mean that today they are no longer considered impediments to the unity of the church, at least to a certain extent. This is the basic line of argumentation that drives the 2013 Roman Catholic–Lutheran document From Conflict to Communion, prepared for the joint commemorations of the fifth centenary of the Protestant Reformation.[3] It is a ninety-page joint statement between the Vatican and the Lutheran World Federation that attempts to summarize what happened in the sixteenth century, the controversies that arose, and the reinterpretation of the whole in light of pressing ecumenical concerns.

After providing a carefully written summary of the main issues that divided the (Lutheran) Reformation and Roman Catholicism, the document ends by suggesting five imperatives for preparing for the commemoration. The first is the following: “Catholics and Lutherans should always begin from the perspective of unity and not from the point of view of division in order to strengthen what is held in common even though the differences are more easily seen and experienced.”[4] Unity, not truth in love, is the main and driving motive. The first imperative is unity above all else. This, however, is not the best way of honoring the Reformation, nor is it a biblical approach to Christian unity. Despite its many shortcomings, the Reformation was nonetheless a cry to have one’s own conscience and the church bound to God’s Word alone. Sola scriptura was the “first imperative” of the Reformation from which all else followed, unity included. It is telling that after five hundred years, ecumenical unity is now the top priority, replacing the authority of God’s Word. There is the risk of elevating “unity” to the absolute principle, a little “god” claiming preeminence. Perhaps this is the ecumenical idol of the day that needs to be addressed in a “Protestant” way, that is, recasting unity under the Word of God and not the other way around.

On the other hand, there is a significant segment of contemporary evangelical theology that continues to see the doctrinal issue epitomized in the sixteenth-century debates on justification as still standing theologically, even though it is presented in more nuanced and graceful ways by the ecumenical climate that has characterized the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Salvation in Christ alone by grace alone through faith alone according to Scripture alone remains a point of separation between the evangelical Protestant reading of justification and the Roman Catholic one.

To underscore the point, several hundred evangelical scholars and leaders around the world signed the 2016 document Is the Reformation Over? A Statement of Evangelical Convictions.[5] This statement is characterized by a biblical parrhesia, namely, the bold conviction that derives from being persuaded by the gospel truth, which, after all, was recovered at the Reformation. The post–Vatican II Roman church, while being more open and nuanced toward biblical authority and salvation by faith alone, still retains a significantly different theological orientation from the classical understanding of Scripture and salvation represented during the Reformation. Dei Verbum (the Vatican II dogmatic constitution on divine revelation) is a masterful exercise of theological aggiornamento (i.e., modernizing) according to the “both-and” pattern of Roman Catholicism at its best. Still, it is not what the Reformation understood concerning sola scriptura. The 1999 Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification (JDDJ), signed by Roman Catholics and Lutherans, comes close to what the Reformation stood for in recovering the good news of salvation as a Christ-given gift, but it tends to blur the lines on significant points. The document reaffirms that on the two basic issues (i.e., the supreme authority of Scripture and justification by faith alone), the Reformers were simply recovering the biblical gospel, which Rome rejected and still does, although in more nuanced and suffused forms.

The comparison between the two readings is the tip of the iceberg of divergent theological orientations, and the fifth centenary of the Protestant Reformation is a welcomed opportunity to study afresh and in depth the whole topic. A modest contribution to the ongoing reflection can be briefly summarized by recalling the steps that led to the present-day ecumenical reinterpretation of the old controversy. To do so, in this chapter the texts of the Council of Trent are examined, as they represent the main Roman Catholic response to the challenges posed by the Protestant Reformation on the doctrine of justification. Trent framed the Roman Catholic understanding of justification for subsequent centuries and thus became a strong reference point for Catholic identity in modern times. This sketched study of the Tridentine view of justification is followed by a bird’s-eye view on the twentieth century’s ecumenical trajectory in which Rome was involved (e.g., Second Vatican Council, Hans Küng, Otto Pesch, Evangelicals and Catholics Together) and that eventually resulted in the JDDJ, providing a theological assessment of the main tenets of this important ecumenical document. In conclusion, some critical remarks are presented concerning the correlation between Trent and present-day discussions of Rome’s position on justification by faith.

*Read Dr. De Chirico’s entire chapter in The Doctrine on Which the Church Stands or Falls.

Endnotes

[1] Parts of this opening section are adapted from Leonardo De Chirico, “140. Is the Roman Catholic Church Now Committed to ‘Grace Alone’?,” Vatican Files (blog), August 1, 2017, http://vaticanfiles.org/en/2017/08 /140-is-the-roman-catholic-church-now-committed-to-grace-alone/; De Chirico, “68. 2017: From Conflict to Communion?,” Vatican Files (blog), November 15, 2013, http://vaticanfiles.org/en/2013/11/68-2017-from-conflict-to-communion/. Used by permission of the author.

[2] Fulvio Ferrario and William Jourdan, Per grazia soltanto: L’annuncio della giustificazione (Torino: Claudiana, 2005), 111.

[3] Lutheran–Roman Catholic Commission on Unity, From Conflict to Communion: Lutheran-Catholic Common Commemoration of the Reformation in 2017, Vatican, accessed July 28, 2018, http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical _councils/chrstuni/lutheran-fed-docs/rc_pc_chrstuni_doc_2013_dal-conflitto-alla-comunione_en.html. Notice that the chosen word is not “celebration” but “commemoration.” Celebration would have implied an element of sober feasting in remembering the Reformation with an attitude of thanksgiving, while not hiding the “dark pages” of Protestant history. On the contrary, in spite of all that is said in Roman Catholic circles about Luther being “a witness of Jesus Christ,” ecumenism cannot celebrate the Reformation. Official Roman Catholicism, even the post–Vatican II and ecumenically minded versions of it, can only commemorate it. It can only remember, ponder, and reflect on it. Yet is the standing legacy of the Reformation to be commemorated only? Is the call to go back to the Scriptures not to be celebrated? Is a Christ-centered, grace-dependent, God-exalting faith not to be celebrated but only remembered? This chapter and this volume answer that celebration is rightly in order.

[4] Lutheran–Roman Catholic Commission on Unity, From Conflict to Communion, 6.239.

[5] Is the Reformation Over? A Statement of Evangelical Convictions, http://www.isthereformationover.com. This website contains the document translated in eight languages and the press release highlighting its main points.