How to Read Jeremiah Theologically

Every prophetic book in the Old Testament bears witness to the reality that the nation of Israel lived—like us—in a divinely charged universe where culture, politics, and religion were inseparable from the sovereign power of God in the world. As the true king over all creation and Israel’s covenant Lord, there was no area of life left unaffected by Yahweh’s reign. And there is perhaps no book that better captures the covenant realities of judgement coming against God’s people in the Old Testament and the new covenant hopes prophesied and fulfilled in the New than the book of Jeremiah.

One of the reasons the book is so informative is because of its size: 52 chapters in the Masoretic Tradition.[1] The amount of material and illusive structure of the book have presented challenges to interpreters seeking to get at the theology of the book. Much attention has been given to Jeremiah’s relationship to Deuteronomy, especially regarding proposals of complex literary strata and editorial activity. While the size and complexity of the book cannot be denied, Gordon McConville is no doubt on solid ground when he writes that a theological approach “requires that the book is the product of careful and sophisticated editing, substantially the work, as I believe, of one mind.”[2]

Within this carefully crafted corpus, we see a raucous political landscape that stretches from Babylon to Egypt. The context of Jeremiah’s ministry (627 BC down to the 570s) intersected with massive transitions and events, from the declining hegemony of the Assyrian Empire to the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians. The historical setting of the book, as well as its abundant autobiographical and biographical material, reveals how the words of God—through Jeremiah (Jer. 1:9)—break into real time and space “to pluck up and to break down, to destroy and to overthrow, to build and to plant” (Jer. 1:10).

Covenant Consequences

The theological context of Israel’s judgement in Jeremiah is the covenant God established with his people through his prophet Moses at Mount Sinai. Like “a stubborn and rebellious son who will not obey the voice of his father” (Deut. 21:18), God describes the inhabitants of Judah, saying, “But this people has a stubborn and rebellious heart; they have turned aside and gone away” (Jer. 5:23). God promised Israel when they went into the Promised Land that he would provide rains for their crops and animals, giving them all they would need (Deut. 11:13-15), but Jeremiah informs them that their “iniquities have turned these away, and [their] sins have kept good from [them]” (Jer. 5:25). In Deuteronomy 29:19 Moses warns the people, in the same plant imagery taken up in Jeremiah, saying, “Beware lest there be among you a root bearing poisonous and bitter fruit . . . saying, ‘I shall be safe, though I walk in the stubbornness of my heart.’”

Yet, Jeremiah addresses the foolishness of such false hopes in the gate of the temple. Instead of turning their stubborn hearts toward God, they were resting in the inviolability of God’s house (Jer. 7:1-7). Through the prophet the Lord questions his people: “Will you steal, murder, commit adultery, swear falsely, make offerings to Baal [see Deut. 5:1-21] . . . and then come and stand before me in this house, which is called by my name, and say, ‘We are delivered!’—only to go on doing all these abominations?” (Jer. 7:9-10). Emboldened by their leaders declaring “Peace, peace” (Jer. 6:14), the people walked in rebellion while anticipating divine protection. Instead of proclaiming a word of peace, Jeremiah warned the people of Yahweh’s impending judgement in response to their covenantal rebellion, so that the Lord declares in Jer. 11:8, “Therefore I brought upon them all the words of this covenant, which I commanded them to do, but they did not.”

As those relating to God by the shed blood of Jesus Christ, we no longer live in fear of the Deuteronomic covenant curses laid out by Moses on the slope of Sinai. The writer of Hebrews reminds us that we no longer approach a mountain covered in darkness and gloom (Heb. 12:18-21), but we have been brought into the city of the living God by our new covenant mediator Jesus (Heb. 12:22-24). We should, however, be careful not to overlook the reality that God will judge the wicked (Rev. 6:10) and uphold his covenant consequences—even under the new covenant. God will bring judgment upon those who reject the faith-demands of the covenant inaugurated in Christ, and we must not be people who proclaim “peace, peace” toward those with whom there will not be peace. It is often the case in art and theology that areas of darkness and shadow throw the eye and mind toward the light. Click To Tweet

Idols and the True God

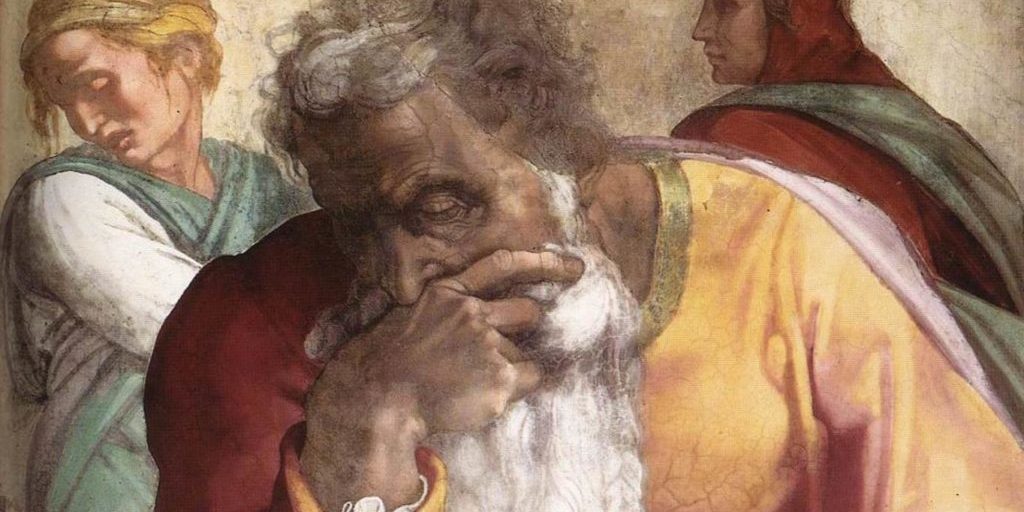

It is often the case in art and theology that areas of darkness and shadow throw the eye and mind toward the light. Sadly, and similarly, much of Jeremiah’s theological portrait is presented as a corrective to the idolatry of God’s people. The book references several pagan deities encountered by the prophet and his audience: Baal (Jer. 2:23; 9:14), the queen of heaven (7:17-19), Marduk (50:2), and Egyptian deities (46:25). Examining these idols, Jeremiah indicts the people over their covenant infidelity, as well as their lack of intelligence (Jer. 10:14; 51:17)! An idol is an object of wood that cannot speak, hear, or act, but “the LORD is the true God; he is the living God and the everlasting King” (Jer. 10:10). Unlike these “scarecrows in a cucumber field” (Jer. 10:5), Yahweh is the God who speaks and acts, so that the book opens with God reporting to Jeremiah, “You have seen well, for I am watching over my word to perform it” (Jer. 1:12).

While the cultural language of ancient Near Eastern idolatry always sounds strange to our twenty-first century ears, Jeremiah’s imagery of idol worship continues to resonate with human hearts so prone to wander (Jer. 17:9). In chapter 2, the Lord brings charge upon his people saying, “they have forsaken me, the fountain of living waters, and hewed out cisterns for themselves, broken cisterns that can hold no water” (Jer. 2:13). The great crime committed by God’s people in Jeremiah’s day is that same sin that continues to plague all of humanity. We continue to exchange the God who would give us living water (John 4:10) for broken, dusty, and dry replacements that resemble a tomb more than a source of life.

Restoration and a New Covenant

Despite the exhaustive portrait of Judah’s idol-induced covenant faithlessness, the book of Jeremiah points toward God’s unwavering covenant commitment to restore his people through the establishment of a new covenant. After the storm of the Lord’s judgement has passed (Jer. 30:24), God declares at that time, “I have loved you with an everlasting love; therefore I have continued my faithfulness to you” (Jer. 31:3). The book makes it clear that judgement will come, on account of the people’s sin, but that judgement will not be the final divine act in God’s redemptive work. In language that parallels the promises of judgement, God will plant them back in the land, unify them with one heart, rejoice in their good works, and make with them an everlasting covenant (Jer. 32:36-41). We continue to exchange the God who would give us living water for broken, dusty, and dry replacements that resemble a tomb more than a source of life. Click To Tweet

The new covenant described in Jeremiah is presented in clear relief to the old covenant established at Sinai. In fact, the Lord states it is “not like the covenant that I made with their fathers on the day when I took them by the hand to bring them out of Egypt, my covenant that they broke” (Jer. 31:32). Jeremiah prophesies of a day when God’s covenant expectations will be inscribed upon the hearts of his people, not tablets of stone, and the people of God will all know him as their covenant Lord. The passage also points to the fact that God will not deal with his people according to their sin, but he “will remember their sin no more” (Jer. 31:34). It is not as though Yahweh forgets, but that he will no longer deal with his people according to the consequences of their sin. How is this to be accomplished? While Jeremiah does not make the connection explicit, the New Testament reveals that it will be through the vicarious suffering and atonement provided through a new Davidic king—“a righteous Branch” who will deliver God’s people reign forever (Jer. 33:15-17).

The New Testament records the impact the book of Jeremiah had on the apostles’ teaching about Jesus and the inauguration of the new covenant. Hebrew 8:8-13 quotes Jer. 31:31-34, concluding, “In speaking of a new covenant, he makes the first one obsolete. And what is becoming obsolete and growing old is ready to vanish away” (Heb. 8:13). By no means is this text intended to disparage the inspired nature, revelatory value, or continued significance of the Old Testament Scriptures. Instead, what it does explicitly state is that in Christ, Jeremiah’s “Behold, the days are coming . . . ” finally arrived.

Endnotes

[1] The Early Greek translation of Jeremiah found in the Septuagint is approximately one-seventh shorter than the text recorded in the Masoretic text. See Andrew Shead’s A Mouthful of Fire: The Word of God in the Words of Jeremiah (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2012), 47-52 for a brief and helpful discussion of the relationship between the two manuscript traditions.

[2] J. G. McConville, Judgement and Promise: An Interpretation of the Book of Jeremiah (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1993), 23.