The God of Scripture and the God of the Philosophers

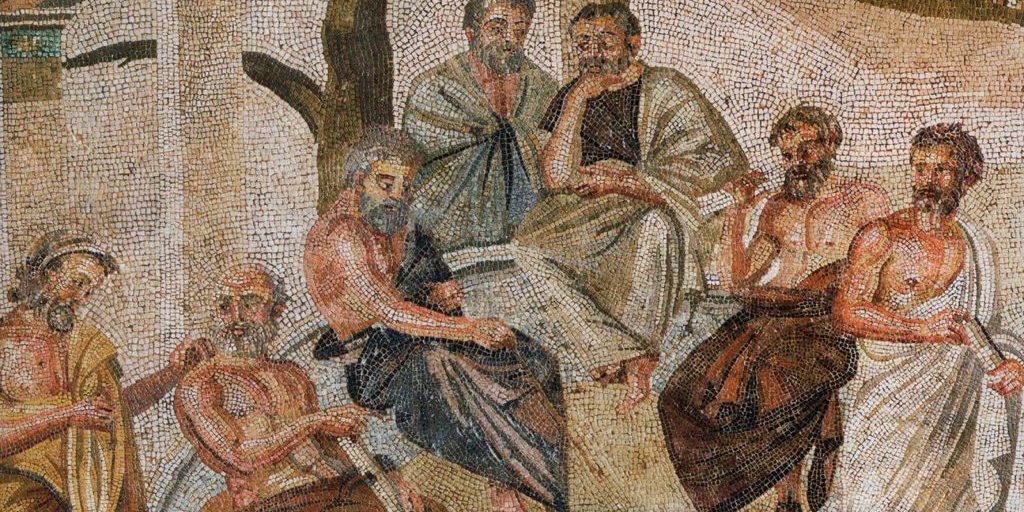

In this article I want to discuss a proof for the existence of the First Cause that comes from Aristotle. I am indebted to the excellent description of Aristotle’s argument provided by Ed Feser in Ch. 1 of his book, Five Proofs for the Existence of God (Ignatius, 2017).

Change Requires a Changer

Change occurs. We observe this every day of our lives. This is the starting point of the argument. We see qualitative change, change of location, change in size, and substantial change (as for example when a living thing dies). Parmenides had argued that all change is an illusion because he thought that actual change is impossible. For example, a cup of coffee cools down. It was hot and then it became cool. How can the coldness of the coffee come into existence out of nothing? It is impossible. So, he argued, it must be our senses deceiving us. But Aristotle argued that the coldness does not come out of nothing but rather is an actualization of the potential contained in the coffee. The coffee always was potentially cold and just needed something (like cool air) to actualize that potential. This led him to state a fundamental principle: change requires a changer. Only what is actual can do anything. So, when a change occurs, that change requires a changer.

If we analyze the changes that take place all around us every day, we find that all of them have causes (changers) and these causes can be understood in series with one thing actualizing another and that thing itself being actualized by something else. The Aristotelian proof does not claim that there had to be a First Cause to get the whole sequence of causes started; Aristotle himself thought that the material world had always existed. No, the Aristotelian proof claims that the series of causes we observe in the material world must be traceable back to a cause that is not itself caused, that is, to an Unactualized Actualizer. The significance of the First Cause is not just that it is “first” but that it is the kind of cause that requires no cause because it is Pure Act, that is, all actuality and no potential. The point of the argument is not that without the First Cause the universe could not have gotten started; it is, rather, that without the First Cause no change would be occurring right now. The Aristotelian argument actually proves that the First Cause is causing the world to be the way it is at every moment of every day.

A possible objection would be that perhaps the series of causes is infinite. Perhaps the series has no beginning. In order to understand why this is impossible, it is necessary to distinguish between two kinds of series of causes, namely a hierarchical series versus a linear series. A hierarchical series of causes has to have a first member, but a linear series does not. A hierarchical series is a series of causes that simultaneously act to produce effects. For example, a coffee cup sits on a desk, which holds it up while itself being held up by the floor and so on. If any one of the members of this series ceased to exert causal power the coffee cup would fall down. All have to be working at once. On the other hand, in a linear series once a thing is caused by a prior member of the series the prior member can pass out of existence without affecting the thing it caused while it was in existence. For example, a boy does not cease to exist when his grandfather dies. What is crucial to understand is that the hierarchical kind of series of causes is more fundamental to reality that the other kind. Why? This is so because every linear series presupposes a series of the hierarchical kind. When we analyze change as requiring the actualization of potential, we realize that at some point there must be a cause that does not itself need to be actualized and yet can actualize (that is, cause) other things because it is pure actuality. If there were no First Cause, we would not exist so we would not be talking about it. Nothing would exist. There would be no being. Why? There can only be something in existence when potential is being actualized and only actuality can cause potential to be realized. So, if there is no First Cause then there is no way for any potential to be realized – not way back at the beginning – but right now.

I want to emphasize that this argument (which I have only sketched hastily here) depends on ordinary reasoning ability and ordinary, common human experience. It resonates deeply with our intuition that the world requires a cause. Aristotle said that philosophy begins in wonder and most of us have had the experience of gazing up at the starry heavens overwhelmed by the sheer wonder of our existence and the existence of this amazing world we inhabit. Most people have to be “educated” out of belief in God. Most people, when you explain the options to them, rightly suspect that Aristotle is right, and David Hume is wrong. And logical reasoning confirms it.It resonates deeply with our intuition that the world requires a cause. Click To Tweet

The Unactualized Actualizer

Make no mistake, the church fathers, when confronted with the Platonic tradition and its belief that the changing world of flux depends for its existence on an unchanging, eternal, simple, perfect, self-existent First Cause (or Unactualized Actualizer), knew immediately that what the philosophers had discovered was God. They recognized that what Aristotle was talking about was providence and the First Cause was the Creator God of Genesis 1. To say anything else would be to leave open the possibility that the God of Israel who became incarnate in Christ was just the tribal deity of the Jews and Christians and not the supreme cause of the universe. To do that would be to retreat into mythology and see God as a mere being among beings, that is, as one of the things in the cosmos, albeit the greatest of all. The fathers knew that the First Cause of Platonic philosophy was the personal God who speaks and acts in history to judge and save his people. He is the transcendent Creator and sovereign Lord of history who alone is to be worshipped. He is not part of the world caused by the First Cause of the philosophers. While the God of the Bible certainly cannot be reduced to the impersonal First Cause of Aristotle, the God of the Bible also certainly is not less than or derived from the First Cause. The conclusion they were driven to was that the God of the Bible is the First Cause.

When they read Exodus 3 in the light of this discussion, they noticed that the LORD reveals himself to Moses as the One in whom existence is part of his essence: “I Am.” This seemed to them to be a different way of saying that God is the one who is Pure Act, pure actuality with no potentiality at all. As such God is eternal and immutable. He causes but is not caused. He is simple because he is not a mixture of actuality and potentiality. He is eternal because he simply is while created things come to be and then change only to finally pass out of being. God is.

Thomas Aquinas, in the first 43 questions of the Summa Theologica merely summed up the patristic consensus in presenting God as the eternal, simple, immutable, self-existent First Cause of the cosmos. The Trinitarian classical theism of the tradition is expressed classically in this work, but its roots reach back into the Bible itself. It is a mixture of general revelation and special revelation in which special revelation supplements and corrects general revelation. Although Aristotle thought the First Cause was impersonal, Scripture reveals that God speaks and acts. Although Aristotle thought that the cosmos was eternal, Scripture reveals that it was created ex nihilo. Although Aristotle thought that providence is a matter of impersonal causation, Scripture reveals that providence is personal, teleological, and an expression of God’s love for his creation. The God of the Bible is more than the God of the philosophers, but not less.

**This post was originally published through Dr. Carter’s newsletter which can be accessed here: The Great Tradition.”