Bavinck on Historical Criticism: The Search for the Essence of Christianity

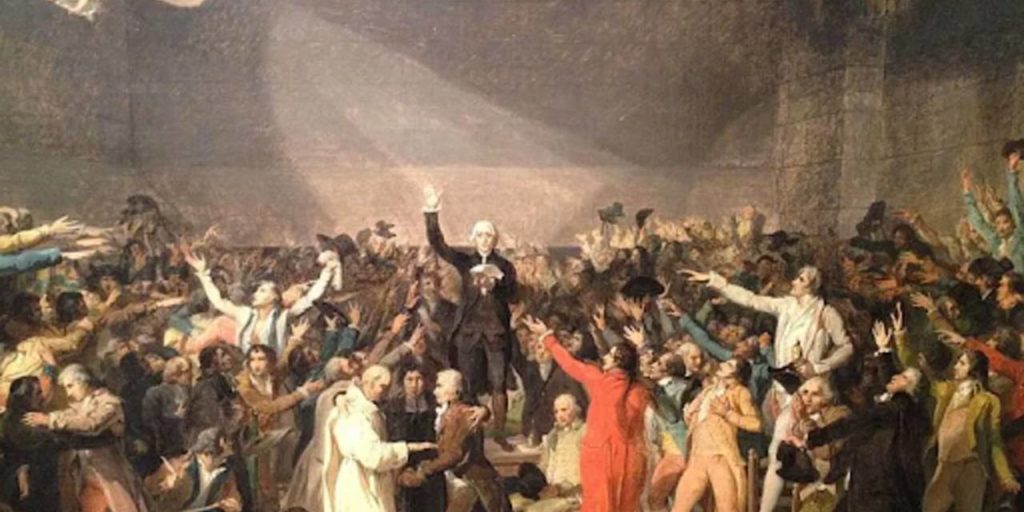

In a 1906 article re-published in the volume, Essays on Religion, Science and Society, Herman Bavinck addresses the topic of “The Essence of Christianity.” Adolf von Harnack had delivered his famous lectures on this topic in Berlin in 1900 (ET What is Christianity? 1901). Bavinck sees the search for the essence of Christianity as arising in the eighteenth century as a result of the need to discover an alternative interpretation of Christianity to the orthodox Christianity seen in dogma, worship and the confessions going back to the beginning of the church. Although he does not say so explicitly, he strongly implies that the crisis of the Enlightenment caused a loss of faith in traditional Christianity, which in turn prompted a search for “a new kind of Christianity” that could be embraced by people whose primary commitment was to the ideals of the Enlightenment – above all the final authority of Reason.

Historical Misconceptions

Bavinck surveys Schleiermacher, Kant, Hegel and Schelling. Schleiermacher located the essence of Christianity in the “complete and unremitting God-consciousness” of Christ. For Kant, Christ is at most a symbol of a humanity pleasing to God. Comparing Schleiermacher to the Deists of the eighteenth century Bavinck damns him with faint praise “In Schleiermacher’s construction of the essence of Christianity, one finds at least this positive element: the person of Christ again came to the foreground.” (34) For Schelling, Christ was the highest revelation of God’s incarnation in creation and for Hegel Christ was the consciousness of the pre-existing unity of God and creation. But the main figure with whom Bavinck engages in this essay is David Strauss and the issue that arises with him involves the interpretation of Scripture by means of historical criticism. Strauss argued that the implication of Hegel’s philosophy is that the divine idea cannot be expressed in just one individual. So the relationship between the God-humanity union and the historical person of Christ is problematized. Who is Jesus? is a question that must be investigated by historical research, a study of the sources. It is presumed that the historical figure of Jesus will not be the “Christ of the congregation.” Schleiermacher’s Christ is the religious fantasy of the congregation and so the historical Jesus is not the Christ of faith.Bavinck notes that the ensuing search for the historical Jesus unearthed as many “Jesus figures” as scholars. When Harnack gave his famous lectures, he argued that the essence of Christianity is the experience [Erlebnis] that God is their Father and they are his children, which experience is derived from “the appearance, teachings, and life of Christ.” (36) Christianity proclaims the fatherhood of God and the nobility of the human soul, which two truths constitute the essence of Christianity. Jesus is not the object of faith himself, he is the first to have faith in God the Father; he is the first Christian.For Bavinck, what Harnack is proposing is a new interpretation of the meaning and message of Jesus, an alternative to the Trinitarian and Christological doctrines enshrined in the creeds of the early church. Share on X

Bavinck surveys Schleiermacher, Kant, Hegel and Schelling. Schleiermacher located the essence of Christianity in the “complete and unremitting God-consciousness” of Christ. For Kant, Christ is at most a symbol of a humanity pleasing to God. Comparing Schleiermacher to the Deists of the eighteenth century Bavinck damns him with faint praise “In Schleiermacher’s construction of the essence of Christianity, one finds at least this positive element: the person of Christ again came to the foreground.” (34) For Schelling, Christ was the highest revelation of God’s incarnation in creation and for Hegel Christ was the consciousness of the pre-existing unity of God and creation. But the main figure with whom Bavinck engages in this essay is David Strauss and the issue that arises with him involves the interpretation of Scripture by means of historical criticism. Strauss argued that the implication of Hegel’s philosophy is that the divine idea cannot be expressed in just one individual. So the relationship between the God-humanity union and the historical person of Christ is problematized. Who is Jesus? is a question that must be investigated by historical research, a study of the sources. It is presumed that the historical figure of Jesus will not be the “Christ of the congregation.” Schleiermacher’s Christ is the religious fantasy of the congregation and so the historical Jesus is not the Christ of faith.Bavinck notes that the ensuing search for the historical Jesus unearthed as many “Jesus figures” as scholars. When Harnack gave his famous lectures, he argued that the essence of Christianity is the experience [Erlebnis] that God is their Father and they are his children, which experience is derived from “the appearance, teachings, and life of Christ.” (36) Christianity proclaims the fatherhood of God and the nobility of the human soul, which two truths constitute the essence of Christianity. Jesus is not the object of faith himself, he is the first to have faith in God the Father; he is the first Christian.For Bavinck, what Harnack is proposing is a new interpretation of the meaning and message of Jesus, an alternative to the Trinitarian and Christological doctrines enshrined in the creeds of the early church. Share on X

Is this New Interpretation Justified?

Bavinck takes this interpretation of Christianity and asks if it is justified by historical research into the origins of Christianity. For Bavinck, what Harnack is proposing is a new interpretation of the meaning and message of Jesus, an alternative to the Trinitarian and Christological doctrines enshrined in the creeds of the early church. The question is: “Is this new interpretation justified?” Bavinck points out that all the heretical versions of Christianity down through the ages from Anabaptism, Socinianism, rationalism and pietism, to Kant and Schleiermacher to Hegel and Schelling to Strauss and Feuerback and eventually to Harnack – all of these were not new but only revivals of views already proposed in the early church but rejected by the church for good reasons. Central to the church’s decision to reject such ideas of a human but not divine Jesus is history. Bavinck notes that the account Harnack provides of early church history in which a merely human Jesus is gradually elevated to a divine status by ecclesiastical authorities styled “early Catholicism” is a tale invented to justify a view of Jesus already arrived at on other grounds. In other words, the historical method has hidden within itself theological and philosophical presuppositions that determine the final outcome of the “search” a priori.

Bavinck critiques historical criticism as not really historical in the sense of being merely an open-minded search for truth. It is instead the re-telling of history according to a different philosophical axioms and different theological doctrines. The problem with historical criticism is that it is not historical enough – or not historical in the right way. Bavinck presses home the devastating critique that historical criticism is philosophical dogma disguised as neutral method.Bavinck presses home the devastating critique that historical criticism is philosophical dogma disguised as neutral method. Share on X

Bavinck notes that after Strauss “nearly everyone took the route of historical criticism to arrive at knowledge of the essence of Christianity.” (40) The whole enterprise was based on the assumption that the Christ of the creeds could not possibly be the Jesus of history because the human individual cannot “contain” divinity. But since the fact is that God became flesh in Jesus of Nazareth, this means that such an approach to historical research “does violence to phenomena and is nowhere capable of consistent application.” (40) Harnack begins by saying that what constitutes Christianity is a historical question and will be answered by historical research. But “Harnack unavoidably brings along a certain view” and that view “excludes all miracles, because miracles would be a violation of natural laws.” (41) Harnack’s doctrinaire anti-supernaturalism is the foundation, not the outcome, of his “historical approach.” It is a philosophy derived from rational speculation, not a discovery of historical research.

The Inseparability of Philosophy and History

What I find so interesting about Bavinck’s analysis of Harnack is that he so clearly links together the post-Kantian philosophy of Hegel, Schelling and Strauss with the rise and nature of historical criticism. Why did historical criticism take the path it did in the nineteenth century? It did so because it started from certain metaphysical doctrines. Which ones? It started from the Kantian assumption that Hume and the Enlightenment had demolished the classical metaphysics of God as the transcendent Creator of the cosmos. Hegel, Schelling and Strauss were working on the assumption that some form of philosophical naturalism must be true. Since there is not transcendent Creator, God must be re-conceptualized as some aspect of the cosmos. Pantheism identifies God with the cosmos as a whole and all the options are some form of this. Some see God as manifest in the Christ; others see the Christ as uniquely conscious of God. Some see the Christ as a symbol of the church’s faith in God. The views of Hegel, Schelling, Harnack and company are, in fact, reducible to old heresies from church history: “What appears to be new is often very old.” Share on X

Bavinck insists that both the “church-dogmatic” and the “historical-scientific” views of Christianity “contend to be the ‘historical, authentic understanding of the gospel.’” He is resisting the oft implied idea that old dogma is just superstition and tradition, whereas liberal theology is scientific and based on up-to-date research. The views of Hegel, Schelling, Harnack and company are, in fact, reducible to old heresies from church history: “What appears to be new is often very old.” (41)

Faith Seeking Understanding

Bavinck goes on to argue for orthodoxy as the true historical form of Christianity from earliest times to the present. The New Testament itself contains the highest form of Christology, which Chalcedon codifies and systematizes. But Chaldecon does not add new content to New Testament Christology. The idea that the divinity of Jesus was derived from pagan superstition is not supported by the fact that Paul and the Synoptics both portray Jesus as divine. The attempt to re-date the New Testament to the second century floundered on the rock of the four cardinal letters of Paul being incontestably early and on the self-witness of Jesus himself as attested in the earliest gospels. Bavinck concludes: “Open-minded historical research thus leads to the conviction that Jesus according to his own words and the faith of the church from the beginning was the Christ.” (46) It is important, however, not to overstate Bavinck’s conclusion or we will be misled. He does not say that the divinity of Jesus the Messiah can be arrived at by means of neutral, historical research. Bavinck only says that such research can uncover the fact that the earliest Christians believed this to be so. But faith is required in order to accept Jesus as the Christ: “whoever wants to acknowledge Jesus as divine must be minded to do the will of the Father. ‘The pure of heart shall see God.’” (41) This is a “rigorously scientific statement,” which is to say that it is scientifically demonstrable that the only way to agree with the gospel of the church is to put one’s faith in Jesus Christ. Science leads us to the point of decision, but it does not decide for us. Scholarship and the personal faith of the scholar cannot be divided and kept in air-tight compartments. They inevitably affect one another.Science leads us to the point of decision, but it does not decide for us. Share on X

Bavinck thus opens the door to a dogmatics in which both faith and reason play their parts, a science which is not dogmatically closed off to the mighty acts of God in history. This is a solid basis for a post-critical and theological interpretation of Scripture in which the interpreter perceives the true reality revealed in text, namely, the living God, the transcendent Creator, and the One who became man in the person of Jesus the Christ. The search for the essence of Christianity terminates on the person of Christ, who is historical but received only by faith.

**This post was originally published through Dr. Carter’s newsletter which can be accessed here: The Great Tradition.”