The Regulative Principle and the Corporate Recitation of Creeds

Recently I was paid one of the best compliments I could hope to receive. A colleague told me, “Sam, I know that you are a systematic theologian, but when I think of you, I think: historical theology guy.” This interaction summarizes in a nutshell the kind of systematic theologian I hope to be: one who is richly historical. Commendable, I think, is a deep and abiding suspicion of theological novelty. This disposition of mine translates, in part, into a love of—and vocal self-conscious identification with—creeds and confessions. Probably the most important (and needed) of my creedal commitments is my adherence to the Nicene Creed. Is the corporate recitation of creeds in weekly worship at odds with the regulative principle? Click To TweetMy students will not be surprised to know this about me, since we open all of our classes by corporately confessing the creed aloud. So deep is my appreciation for this creed that I commend its vocal and consistent corporate confession not only in the classroom, but in the weekly worship assembly of the local church. I did not always give this commendation, however, on account of a difficulty I had with squaring the practice with another deep conviction I have regarding the Regulative Principle of corporate worship. It took me a while to wrestle with this issue, and while I did, I searched to little avail for resources that addressed the specific question: is the corporate recitation of creeds in weekly worship at odds with the regulative principle? Having arrived at an answer I am satisfied with at the personal level, I have decided to summarize the answer for others who may be in a similar place to the one in which I found myself—this is the article I wish I had read.

What is the Regulative Principle?

We begin with definitions. What exactly is the regulative principle? The first thing we have to say about the regulative principle is that it is, in fact, a principle. Therefore, I do not take it to be a strict prescription in a thoroughly fine-tuned sense. While many may argue for exclusive psalm-singing or a capella or a specific order of service, I do not think you can get that much specificity out of this idea. The regulative principle is the idea that in principle, our corporate worship is regulated by the word of God. The regulative principle is the idea that in principle, our corporate worship is regulated by the word of God. Click To TweetThis regulative principle is often contrasted with what we might call the normative principle, which also looks to God’s word for instruction, but in a manner that differs from the regulative principle. Where the regulative principle looks to God’s word to receive instructions on the only things to include in corporate worship, the normative principle looks to God’s word to see if a worship practice is consistent or at odds with the Scriptures. The regulative principle uses Scripture in a more prescriptive manner, whereas the normative principle uses Scripture in a more prohibitive manner (whatever Scripture prohibits, normative principle churches stay away from). Underneath the regulative principle is the conviction that God has never left his people without instruction for how they ought to worship him. The people of God have never had to guess what God wants in worship. So, what does this mean for local church weekly worship?

When it comes to the New Testament Church, his word commands Christians to (1) read the Scriptures publicly (1 Timothy 4:13), (2) teach/preach the Scriptures (1 Timothy 4:13; 2 Timothy 4:1-2), (3) pray (1 Timothy 2:1; Acts 2:42; 4:23-31), (4) sing (Colossians 3:12-17), and (5) practice the ordinances of baptism and communion (Matthew 28:19; Acts 2:38; 1 Corinthians 11:23-34). The regulative principle is the commitment to build the corporate worship service around—and only around—those five elements. Underneath the regulative principle is the conviction that God has never left his people without instruction for how they ought to worship him. The people of God have never had to guess what God wants in worship. Click To TweetThis rationale assumes that if God desired for our corporate worship to include anything else, he would have said as much in his word. Theologically, the regulative principle seems to follow directly from Christ’s lordship of his Church (he sets the agenda), the sufficiency of Scripture (the word of God is capable to do the work of God among the people of God—an innovative posture seems to imply that we could improve upon what God has expressly told us to do), and the fact that God is not indifferent about how he is worshipped (as Nadab and Abihu can testify [Leviticus 10]). So, when asked the question, “Can we go beyond what Scripture commands in our corporate worship?” I respond with, “Why on earth would we want to?”

Additionally, the regulative principle strikes an important chord in the heart of pastoral ministry. Whatever a local church does in worship that local church’s pastors bind the consciences of her members to practice. That is no small thing. When a church gathers, she gathers as a single body to worship her King. The weekly gathering is not an expression of individual and autonomous self-expression, which means if a church includes an element in its corporate worship that is not expressed in Scripture (i.e., baby dedications, movie clips in the sermon, interpretive dance routines, special songs, etc.), the conscientious member who objects cannot simply opt out on the personal level. He is there as a participant of what the church is doing. The pastors have essentially already declared, “This is our corporate expression of worship.” This is a weighty reality, and so the regulative principle is a way of protecting not only the theological integrity of a church’s worship, but also the consciences of a church’s members and pastors. Pastors should not be afraid to bind the conscience of their members (to say, “you must do this thing”), but they should be downright terrified to go beyond the bounds of Scripture in their conscience-binding prescriptions.The regulative principle was first articulated and defended formally by the reformers and their subsequent heirs, which is why it is a staple in the Reformed tradition. Click To Tweet

You are, I trust, beginning to see the potential tension this principle creates with the notion of corporately confessing an extra-biblical statement like the Nicene Creed. Is this something pastors really have the jurisdiction to do? Can they bind the conscience of their members to say, “This is how our church will worship—by confessing our faith in the God expressed in these doctrinal formulations?” I think the answer is yes, but it is an answer that will require a bit of work.

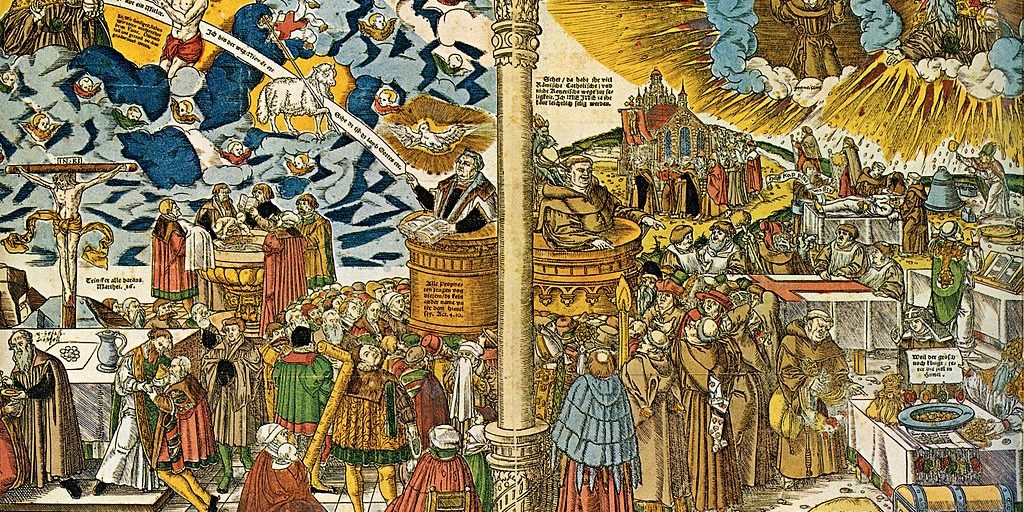

At the very least there is a historical and circumstantial argument to be made here. The regulative principle was first articulated and defended formally by the reformers and their subsequent heirs, which is why it is a staple in the Reformed tradition. Yet, these articulators and defenders of the regulative principle almost uniformly endorsed and practiced the corporate confession of creeds in their worship gatherings. By all appearances, they simply took for granted that confessing the creeds in worship is consonant with the regulative principle. It does not seem as though they even agonized over the question. So, historically, and circumstantially, I think we are safe to conclude that corporate confession of creeds is not at odds with the regulative principle; but how and why this is the case needs some elaboration.

The Biblical Rationale of Creeds

A creed is a statement of faith; a codified and summarized list of essential markers of belief. Creeds are an irreducible feature of the regula fidei (the rule of faith), which constitutes established boundary markers of orthodoxy. Creeds are an irreducible feature of the regula fidei (the rule of faith), which constitutes established boundary markers of orthodoxy. Click To TweetWhen Jude speaks of “the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3), that word “faith” describes a body of doctrines handed to the faith. It had edges and definitions—by describing the faith was for all delivered to the saints, Jude was demarcating the fact that there is an “in” and an “out” of orthodox Christian belief. Apostacy and heresy are unintelligible concepts apart from the regula fidei.

When the Bible speaks of apostasy and people swerving from the truth and departing from the faith (e.g., 2 Timothy 3:1-8), it positively requires the regula fidei and, at the very least, tacitly endorses something like a creed. How can the church hope to continually hand down the “faith once for all delivered to the saints” if that faith is not summarized and codified in an essential way? Heretics always claim to be faithful Christians, and they always work with the very same data of revelation—they use the same scriptural prooftexts as the orthodox when they argue their case, but they interpret them in a manner that does not accord with “the faith once for all delivered to the saints.” So, are we to reinvent the wheel for every generational departure from sound interpretation of Scripture, or might we use a creedal litmus test to demarcate which proposed doctrines are orthodox and which are not?

This “litmus test” is precisely how creeds have functioned throughout the life of the Church in history. If creeds do the work of defining orthodoxy, confessions do the work of defining ecclesial identity of the diverse expressions of orthodoxy Click To TweetThey define the essential marks of orthodoxy, and therefore, those who find themselves at odds with the creeds were considered heterodox at best (i.e., their beliefs were outside the bounds of orthodoxy) and heretical at worst (i.e., their beliefs undermine and directly contradict the heart of Christianity). Historical confessions do not do this much heavy lifting, primarily because they are intrinsically unable to maintain the ecumenical scope and catholicity of creeds like the Apostles’ Creed or the Nicene Creed. Rather, the historical confessions exist to give ecclesiological and denominational doctrinal coherence for a particular body of believers who exist within the larger context of orthodox faith (which is why the historical confessions of the Reformation, for example, go out of their way to reaffirm the doctrinal commitments of the creeds, even when they go on to list their ecclesial and doctrinal distinctives). If creeds do the work of defining orthodoxy, confessions do the work of defining ecclesial identity of the diverse expressions of orthodoxy. Which is to say, confessions have a very modest goal in contrast to the goal of creeds, which is very ambitious and binding.

But we can say even more. Not only does the Scripture tacitly endorse the reality of creeds, it provides a cogent rationale for their existence. In his excellent little treatment, T he Need for Creeds Today: Confessional Faith in a Faithless Age (Baker Academic, 2020), J.V. Fesko argues cogently along these very lines. For example, Fesko notes how God instructs the people of Israel to pass on the testimony of his deliverance to subsequent generations (Exodus 13:14-15). While you do find the Lord prescribing creedal formulations in language he explicitly gives them (e.g., the shema of Deuteronomy 6:4-5), the example from Exodus is different. In this passage, God divinely prescribes tradition, which the people are to articulate in their own words. This precise sort of command is repeated in the New Testament when the apostle Paul instructs the Thessalonians to “stand firm and hold to the traditions that you were taught by us, either by our spoken word or by our letter” (2 Thessalonians 2:15). God’s affirmation of man-wrought traditional formulations is made even more clear when the Scripture on occasion picks up such formulations and codifies them as inerrant, inspired, and authoritative divine revelation. Examples of such occasions are the “trustworthy sayings” in 1 Timothy 1:15; 3:1; 4:7-9; 2 Timothy 1:11-13; and Titus 3:4-8. In these examples, the apostle Paul picks up and legitimizes confessional statements that were already in circulation among the churches. They come to us as Scripture only after they organically sprung up among the people of God. Fesko notes,

he Need for Creeds Today: Confessional Faith in a Faithless Age (Baker Academic, 2020), J.V. Fesko argues cogently along these very lines. For example, Fesko notes how God instructs the people of Israel to pass on the testimony of his deliverance to subsequent generations (Exodus 13:14-15). While you do find the Lord prescribing creedal formulations in language he explicitly gives them (e.g., the shema of Deuteronomy 6:4-5), the example from Exodus is different. In this passage, God divinely prescribes tradition, which the people are to articulate in their own words. This precise sort of command is repeated in the New Testament when the apostle Paul instructs the Thessalonians to “stand firm and hold to the traditions that you were taught by us, either by our spoken word or by our letter” (2 Thessalonians 2:15). God’s affirmation of man-wrought traditional formulations is made even more clear when the Scripture on occasion picks up such formulations and codifies them as inerrant, inspired, and authoritative divine revelation. Examples of such occasions are the “trustworthy sayings” in 1 Timothy 1:15; 3:1; 4:7-9; 2 Timothy 1:11-13; and Titus 3:4-8. In these examples, the apostle Paul picks up and legitimizes confessional statements that were already in circulation among the churches. They come to us as Scripture only after they organically sprung up among the people of God. Fesko notes,

These five trustworthy sayings cover a range of topics, including redemption, church order, and ethical conduct. But the fundamental principle that underlies them all is that the church appropriated scriptural revelation, restated it in its own terms, and promulgated it within the church. In these five instances, under divine inspiration, Paul incorporated these digested forms of revelation into his own letters, thereby confirming the sayings’ veracity and consonance with earlier revelation. With the closing of the canon and the cessation of new revelation, the revelation-reflection-repetition loop no longer exists. Nevertheless, the fact that the revelation-confession pattern has precedents both in the Old Testament and in the New confirms that, with appropriate scriptural safeguards, there is biblical warrant for the church to create and maintain confessions of the faith.[1]

The Authority of Creeds and its Relevance for the Regulative Principle

Practically, this means that none of the “trustworthy sayings” articulated after the closing of the canon (i.e., extra-biblical creeds) have the same automatic authority that these five did. In other words, extra-biblical creeds are authoritative only insofar as they faithfully articulate a summary of what the Scripture teaches. Creedal authority is fundamentally derivative. Click To TweetWe don’t have the luxury of an apostle quoting the Nicene Creed in an inspired text, turning a “trustworthy saying” into sacred Scripture. But this does not mean that any “trustworthy saying” after the canon’s closing is rendered superfluous or suspect by default. It simply means that such “trustworthy sayings” are to be measured against our norma normans (the “rule that rules”): the Bible. In other words, extra-biblical creeds are authoritative only insofar as they faithfully articulate a summary of what the Scripture teaches. Creedal authority is fundamentally derivative.

And this fact clues us in on a first step towards an answer to our quandary. Again, our question is: Is the corporate recitation of a creed in corporate worship consistent with the regulative principle? The answer depends on how biblically faithful you take the creed to be. When it comes to the Nicene Creed, for example, I struggle to think of a statement that has more historical pedigree to support its claim of biblical fidelity. If the Nicene Creed is not a legitimate articulation of regula fidei to demarcate orthodox trinitarianism from heterodoxy and heresy, I cannot imagine what else would!

To be clear, the Nicene Creed is not Scripture, and therefore derives its authority from Scripture to the degree that it accurately reflects Scripture. And I (together with the better part of two millennia of orthodox Christianity) believe that it does articulate biblical teaching, and therefore carries as heavy a weight of authority as any statement outside of the bible can carry. “I am a Christian” and “I reject the Nicene Creed” seem to be historically oxymoronic statements. Click To TweetFrom a historical point of view, I struggle to imagine how someone can attempt to maintain formal continuity and identity as a Christian (i.e., as a member of the “one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church”—the Church Christ promised to build and against whom the gates of hell would not prevail) if this creedal affirmation is outright resisted. “I am a Christian” and “I reject the Nicene Creed” seem to be historically oxymoronic statements. Again, this is not the case with historical creedal statements like the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England or the Westminster Confession of Faith. Adherents of those confessions may believe that such statements faithfully articulate the Scriptures, but none of them would go so far as to say that professing Christians excluded by those statements are thereby excluded from orthodoxy. But I believe this is precisely what is at stake when it comes to adherents to the Nicene Creed.

Very practically, this means that I absolutely have no objection to pastors binding the conscience of their members to the dogma articulated in the Nicene Creed. Because the Nicene Creed is a derived authority—a “trustworthy saying” that truly and accurately articulates the “faith once for all delivered to the saints”—it is completely within their purview to argue that what is contained therein is essential Christian belief. The very fact that the Reformers do not feel like it is particularly necessary to defend their corporate recitation of the Apostles’ Creed and the Nicene Creed in light of their articulations of the regulative principle implies a great deal. It implies that they ascribed this level of (derived) authority to the creeds.Reciting the Nicene Creed together in a local church worship context amounts to “confessing biblical truth together.” Click To Tweet

Of course, the practice of corporately confessing the Nicene Creed depends on how convinced pastors are in their own minds as to the Nicene Creed’s status. They can, in good conscience, only prescribe its recitation in corporate worship if they truly believe that it is essential Christian belief, and that confessing the Nicene Creed is confessing straightforward biblical Christianity. But if he is convinced of all this, then reciting the Nicene Creed together in a local church worship context amounts to “confessing biblical truth together.” In fact, if you are particularly fastidious regarding the formality of the matter, you can preface the church’s public recitation of the creed with a reading from 2 Thessalonians 2:15, “So then, brothers, stand firm and hold to the traditions that you were taught by us, either by our spoken word or by our letter.”[2] With that command of Paul fresh in your minds, you can go ahead and obey his commend with one voice:

“We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth…”

Endnotes

[1] Fesko, The Need for Creeds Today, 10.

[2] While I had every intention of spelling out the corporate benefits of regularly reciting the Creeds in corporate worship, I think this article is running a little long as is. Besides, I’ve written elsewhere on the benefits of regularly reading the creeds in the personal and devotional context, and everything I say there can be easily translated into a corporate context as well. So, for the interested, see: “The Devotional Benefit of (Regularly) Reading Creeds.”