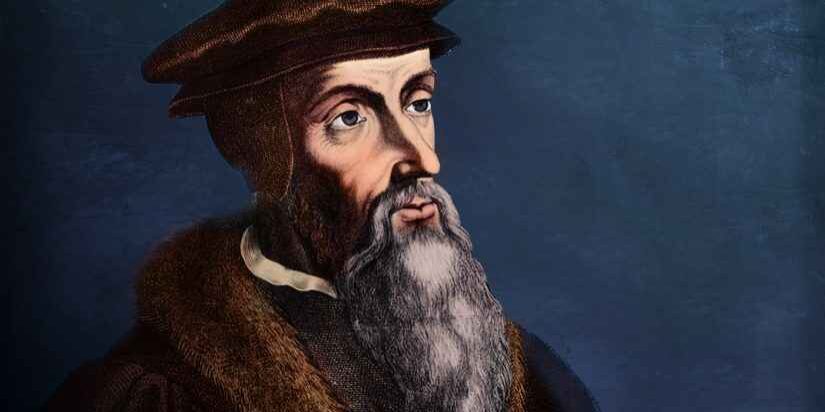

Was John Calvin a Biblicist?

N early half a century after R. T. Kendall published “Calvin and English Calvinism to 1649,” the debate of “Calvin versus the Calvinists” rages on. Kendall’s was not the first attempt at pointing out supposed discontinuity between Calvin and his successors, of course. Years earlier, T. F. Torrance criticized the Westminster Confession for being too scholastic in nature, overtly rationalistic in its teaching on the Ten Commandments, and “markedly less Christological” compared to Calvin and the Reformation.[1] Modern proponents might not be following Kendall in claiming that later Calvinists, like the Westminster divines, are crypto Arminians in their theology, but they are following after Torrance in driving a wedge between Calvin and his Reformed scholastic heirs. Those advocating these views are warning of the dangers of Aristotelian metaphysics and categories employed by various Reformed theologians, as well as the use of natural theology over and against the purely biblical approach of Calvin. The question before us today then, is whether this view is true? Was Calvin a “Biblicist”[2] in his methods? As we will see, the answer is a resounding “no.”

early half a century after R. T. Kendall published “Calvin and English Calvinism to 1649,” the debate of “Calvin versus the Calvinists” rages on. Kendall’s was not the first attempt at pointing out supposed discontinuity between Calvin and his successors, of course. Years earlier, T. F. Torrance criticized the Westminster Confession for being too scholastic in nature, overtly rationalistic in its teaching on the Ten Commandments, and “markedly less Christological” compared to Calvin and the Reformation.[1] Modern proponents might not be following Kendall in claiming that later Calvinists, like the Westminster divines, are crypto Arminians in their theology, but they are following after Torrance in driving a wedge between Calvin and his Reformed scholastic heirs. Those advocating these views are warning of the dangers of Aristotelian metaphysics and categories employed by various Reformed theologians, as well as the use of natural theology over and against the purely biblical approach of Calvin. The question before us today then, is whether this view is true? Was Calvin a “Biblicist”[2] in his methods? As we will see, the answer is a resounding “no.”

Was Calvin a “Biblicist”? The answer is a resounding “no.” Click To TweetBiblicism can be defined as a rejection of everything that is not explicitly made clear or stated in Holy Scripture. Thus, eschewing secondary authorities such as Creeds and Confessions in favor of the Bible as the only authority. This type of argumentation, which also led to a rejection of the use of Aristotelian metaphysics, the Trinity, etc. historically originated from the Socinians. Today the term has been co-opted by some in the Reformed church as a contrast to the teachings of the Great Tradition. This has led to great confusion at best, and at worst, an outright undermining of the Reformed faith.

Calvin’s Use of Aristotle

There is no doubt that Calvin’s successors took a greater interest in metaphysics and philosophy than Calvin himself did. However, this does not mean that Calvin was completely bereft of philosophical categories or usage. Perhaps the most explicit use of Aristotelian categories comes from Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion. As he makes a case for monergistic salvation, Calvin references both Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas:

The philosophers postulate four kinds of causes to be observed in the outworking of things. If we look at these, however, we will find that, as far as the establishment of our salvation is concerned, none of them has anything to do with works. For Scripture everywhere proclaims that the efficient cause of our obtaining eternal life is the mercy of the Heavenly Father and his freely given love toward us. Surely the material cause is Christ, with his obedience, through which he acquired righteousness for us. What shall we say is the formal or instrumental cause but faith? And John includes these three in one sentence when he says: “God so loved the world that he gave his only-begotten Son that everyone who believes in him may not perish but have eternal life” [John 3:16]. As for the final cause, the apostle testifies that it consists both in the proof of divine justice and in the praise of God’s goodness, and in the same place he expressly mentions three others.[3]

As he makes a case for monergistic salvation, Calvin references both Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas. Click To TweetHere we see Calvin employing philosophy in the service to biblical truth, not as the enemy as so many seem want to do today. This is not an isolated usage either, as it is seen not just in Calvin’s theological works, but also his biblical commentaries on Romans and Ephesians. Turning to his exegesis of Ephesians 1, we find that Calvin utilizes the four-fold causality of Aristotle to explain predestination. Calvin writes:

Three causes of our salvation are here mentioned, and a fourth is shortly afterwards added. The efficient cause is the good pleasure of the will of God, the material cause is, Jesus Christ, and the final cause is, the praise of the glory of his grace. Let us now see what he says respecting each.[4]

Many later Reformed scholastic theologians would follow in Calvin’s footsteps in appropriating Aristotle’s thought and four-fold causation in service to theology.[5] For example, the Westminster Confession follows Calvin in this particular appropriation of Aristotelian causality in both the chapters on God’s eternal decree and providence. In the chapter entitled Of God’s Eternal Decree the divines state that “God, from all eternity, did, by the most wise and holy counsel of his own will, freely, and unchangeably ordain whatsoever comes to pass: yet so, as thereby neither is God the author of sin, nor is violence offered to the will of the creatures; nor is the liberty or contingency of second causes taken away, but rather established” (WCF 3.1).[6]

Many later Reformed theologians would follow in Calvin’s footsteps in appropriating Aristotle’s thought and four-fold structure in service to theology. Click To TweetOf course, this does not mean that Calvin’s aim was to formulate an entire philosophical system or even to bring Aristotle to bear upon every text of Scripture. Rather, he recognized that all truth is God’s truth, no matter where it may be found. Therefore, it was not merely Aristotle’s four-fold causality that was useful, but Calvin was willing to go deeper because Aristotle, by virtue of being an image-bearer, was able by common grace to discover various truths or bring about formulations that serviced true theology. We see Calvin’s opinion on the usefulness of Greek philosophy more fully in his commentary on Titus:

From this passage we may infer that those persons are superstitious, who do not venture to borrow anything from heathen authors. All truth is from God; and consequently, if wicked men have said anything that is true and just, we ought not to reject it; for it has come from God. Besides, all things are of God; and, therefore, why should it not be lawful to dedicate to his glory everything that can properly be employed for such a purpose?[7]

He then directs readers to Basil’s discourse “To Young Men,” wherein Basil encourages his readers to draw from classical Greek literature on virtue ethics.[8] Calvin is by no means alone, as later Reformed theologians, such as Samuel Rutherford, utilized Aristotle’s ethics, especially in regard to the subject of habit.[9]

Though there are various opinions on the extent to which Calvin is indebted to men like Aristotle, these brief citations show that, at the very least, Calvin did not completely reject all aspects of Aristotelian philosophy. Rather, he placed philosophy in its proper place, as the handmaiden to the divine text. As Joel Beeke rightly observes:

For Calvin, logic, philosophy, and experience all serve the role of handmaiden to Scripture, and thus their role is to assist in fleshing out and edifying doctrine within a scriptural framework. It is in this light that we must view Calvin’s occasional and non-apologetic use of Aristotelian terms, such as essential and accidental relationships, or primary and secondary causes.[10]

Calvin, like those both before and after him, sought to utilize the best of the world’s great thinkers in service to the Triune God.