How Classical Theism Has Shaped My Life

Like tossing the car keys to a ten-year-old boy and asking him to drive a red sports car, someone handed me a copy of Jürgen Moltmann’s The Crucified God and encouraged me to read it. (Moltmann, who was a towering figure in 20th century theology, died this week at the age of 98.) So, along with a group of four friends, I began to work through my very first theology book. Or, better, it began to work through me. As a young Christian who had given some thought to the so-called problem of evil, the notion of a suffering God was attractive. As a sophomore in college at a secular, state school, I had no theological training to help me critically evaluate what I was reading. As a computer science student, I could do no more than nod along to sweeping claims about Hegel, Kierkegaard, Kant, Camus, and Greek philosophy. I had no business driving that car.

Yet drive I did! It was thrilling to think oneself part of the theological vanguard. As reckless as a child behind the wheel, I put the pedal to the floor and took on board the whole argument: divine passibility, social trinitarianism, Hellenization thesis, collapse of the distinction between the economic and immanent. What could be objectionable? It all felt so delightfully iconoclastic! Kids enjoy breaking things.

I moved on to Moltmann’s Theology of Hope, and then The Church in the Power of the Spirit, and then The Trinity and the Kingdom. I began reading the works of Moltmann’s student, Miroslav Volf, and became convinced that “the Trinity is our social program”. I began reading some Dietrich Bonhoeffer, including his collected Letters and Papers from Prison. Of course Bonhoeffer was right! “Only a suffering God can help!”

In all my reading, I rarely encountered the church fathers or the medieval scholastics. If ever they were mentioned, it was usually with derision or as the foil to an argument. On occasion Augustine, Anselm, or Aquinas might make an appearance to serve as a philosophical or rhetorical prop, but rarely did I find them treated theologically or as theologians. It’s easy to see how “Classical Theism” became a pejorative label to me, a slander to be cast on the pre-Enlightened.

It wasn’t until ten years later that I would come to think of Moltmann’s work—with notable irony—as more pathos than logos, powerfully written and yet full of deeply contested claims. And while, today, I remain grateful for his work and continue to be impressed with his gripping prose, I couldn’t more strongly object to his most enduring theological commitments. I now realize that for ten years, I had been in the grip of a kind of theological spell that I didn’t see or understand. And it wasn’t just Moltmann’s prose. As a campus minister who lives and serves in the context of the modern, secular university, I found that there were other forces that kept me spell-bound. I want to describe some of those invisible forces and what finally delivered me from them.

The Modern(ist) University

If theology is the study of God and all things in relation to God, then the modern, secular university is profoundly anti-theological: the study of all things in independence from God. Rather than submitting to the lordship of the One in whom everything lives and moves and has its being, the dogma of the modern university is simple: no dogmatics allowed.

But in addition to its principled secularism, there are other forces at work in the modern, secular university, which create an environment that makes belief in the classical understanding of God very difficult. I have lived as a student and then as a campus minister in this environment for over twenty years and have come to more clearly see these forces at work and understand the way they apply a pressure on the classical understanding of God.

1. The problem of evil is the controlling question

The modern secular university is known for, among other things, its social activism. Whether it be marches for civil rights, anti-war protests, campaigns for economic development, opinions about international events, or in recent decades, postmodern concerns about power, the secular university has, at least since the 1960s, been animated by social concerns.

Allowing the problem of evil to become the controlling question puts God, rather than sinners, on trial for the evil and suffering of the world. Soteriology becomes inverted. Share on XWhen God or the Christian faith and tradition are brought into dialogue with those social concerns, the conversation inevitably turns to the so-called problem of evil. This means that the modern, secular campus is a theologically hostile environment where apologetics can too quickly become the controlling concern. When that happens, it becomes easy to see how divine passibility, especially of the Moltmannian flavor, becomes an empathetic response to the questions of Christians and non-Christians alike. Troublingly, one passibilist philosopher has stated the ostensible options this way: God either “stands idly by, cooly observing the sufferings of His creatures” or suffers with His creation.[1] If those are the only options, the thought of an empathetic God who suffers as fellow victim of the world’s injustices—this option wins the apologetic day every time.

Apologetic concerns, while important, are undeserving of so much dogmatic sway. They concede too much by allowing the questions of skeptics and non-believers to become the controlling questions for Christian theology. Paul Gavrilyuk has recently noted the way that soteriology has become less about atonement for sin and more about “God becoming reconciled to unjustly suffering humanity.”[2] Allowing the problem of evil to become the controlling question puts God, rather than sinners, on trial for the evil and suffering of the world. Soteriology becomes inverted. But in Christian theology, as in a sport, a strong defense isn’t enough to win games. One needs a more holistic game plan that includes an offense. But that requires a different starting point and different controlling questions.

Yet it was these apologetic concerns in the context of the modern secular university that made divine passibility so appealing to me. The classical understanding of God, when subjected to the questions of skeptics and unbelievers, seemed so much less capable of answering those questions. I was just too young to know any better.

2. The Epistemology of Modernity

Like fish in water, undergraduate students of the modern, secular university are, on average, entirely unaware of the influences of modernity on their studies. So basic and ubiquitous are the modernist influences that, even if discussed in a requisite philosophy or history course, its effects remain implicit and unexamined. Nowhere is this truer than in the hard sciences and STEM disciplines. The objectifying and instrumentalizing of knowledge, the distinction between valid and invalid means of knowing, the hegemony of empiricism—all of it contributes to an environment in which a student feels entirely comfortable declaring to me, as one once did: “I don’t believe in God. I believe in science!”

While not all students have such a facile understanding of the world, that such an understanding can be so easily retained is evidence of the hegemony of empiricism in the STEM corners of the modern, secular university. And that applies a kind of pressure on theology, the Queen of the Sciences. Not a single student would deny the reality of being, consciousness, or bliss.[3] Yet the fact that they elude empirical analysis does no injury to empiricism’s hegemony.

Modernity’s influence on epistemology makes it easy to dismiss the classical understanding of God. In contrast to Nicholas of Cusa’s argument that God is non aliud, or not another “thing”, a Moltmannian-style god whose nature is wrapped up with and ultimately dependent on creation becomes more palatable for empiricists. It fits more tidily into the mechanistic worldview. If God is in time rather than eternity, if creatures can affect God, if God exists on the same ontological plane as creatures, then God becomes aliud. This god is object rather than Subject. This is a god that can be acted upon, analyzed, understood, and even instrumentalized for other purposes. If there is a place for God in the consciousness of the modern, secular university, it’s this god.

3. Humanism and a crisis of teleology

In doxological joy, the Apostle Paul declares of God that “from Him and through Him and to Him are all things” (Rom. 11:36). Classically understood, God is the whence and whither of all things. In Him all things find their source, their being, and their ultimate telos. And yet, insofar as the modern, secular university is committed to the study of all things in independence from God, it is utterly lacking in a unified telos. Academic disciplines and departments, in their diverse multiplicity of values, rules, cultures, and objectives, exert a strain on the university, because they push and pull in competing directions. What is the ultimate goal and end of the modern university? Contributing to a body of knowledge? Technological advancement? Increased enrollment? Perpetuating an intellectual and philosophical heritage? Growing the budget? Improving society? Training civil servants? Cultural production? If a common or unifying telos can be discerned at all, it is ultimately an anthropocentric and humanistic one.

From humanity, and through humanity and to humanity are all things. This is a teleology of human achievement. Its ultimate pursuit is, to borrow from Augustine, incurvatus in se, turned in on itself. How can an environment so oriented toward human production and achievement not exert a kind of pressure on the classical understanding of God? The salvation promoted by the university is a kind of pro nobis that terminates with self and never returns to the glory and majesty of Holy God. Salvation—be it my self-actualization, my career placement, my contributions to research, etc.—is ultimately about me.

The prevalence of humanistic values and goals makes a self-serving theology more attractive. A passible god who empathizes with me just feels superior. A god who is affected by me and is changed by me just makes sense. A god whose being is wrapped up with creation makes me feel so important.

Of course, there were other forces at work—some not of this world (Eph. 6:12)—but I am convinced that these forces function like gravity, somewhat invisibly, pulling away from the classical understanding of God. They make the campus of the modern, secular university a place where the historic beliefs of the Great Tradition seem initially less plausible. At least they did for me.

Breaking the Spell of Modernism

My theology should begin with God and God’s self-revelation rather than adopting the methodological strictures of modernity. Webster gave me the freedom to think about God theologically. Share on XIf these modernist forces—reconciling God to human suffering, modernist epistemology, and humanist values and goals—exert such a powerful force on classical theology, how is the spell of modernism to be broken? In my own life, it took ten years to wake up to the spell I was under and break free. I’ve spent another ten years reflecting on how I ended up so far from the Great Tradition, and the best I can do is recount the countervailing forces that helped deliver me from the gravitational pull of The Crucified God.

First, no one helped remove the scales from my eyes more than John Webster. Like an encounter on the Damascus road, reading “Theological Theology”,[4] Webster’s justly famous inaugural addresses as the Lady Margaret Chair of Divinity at the University of Oxford, changed me on the spot. Webster helped me see how truly controlled theology had become by modernist values. I saw how my entire understanding of God had been constructed out of naturalistic, even atheistic, assumptions in order to reconcile God to a modernist worldview. I was born in Babylon and didn’t know it could be different. Webster helped me think theologically without the anxieties of modernity whispering in my ear. The so-called problem of evil didn’t need to control my theology. The historical-critical method of interpretation, while not un-important, didn’t get to make final theological pronouncements. My theology should begin with God and God’s self-revelation rather than adopting the methodological strictures of modernity. Webster gave me the freedom to think about God theologically.

Second, I began reading the church fathers and understanding the reasons for their dogged commitment to impassibility. Paul Gavrilyuk[5] and Jaroslav Pelikan[6] helped me to see that Christianity did not become captured by Greek philosophy, but rather appropriated the highest intellectual tools of a culture to account for the biblical distinction between God and creation that was so central to the earliest christological and trinitarian debates. J. Warren Smith[7] helped me see the technical nuance of Cyril of Alexandria’s understanding of impassibility. The early church fathers weren’t Hellenistic philosophers who lacked self-awareness, they were brilliant theologians who were making theological sense out of complex passages of Holy Scripture.

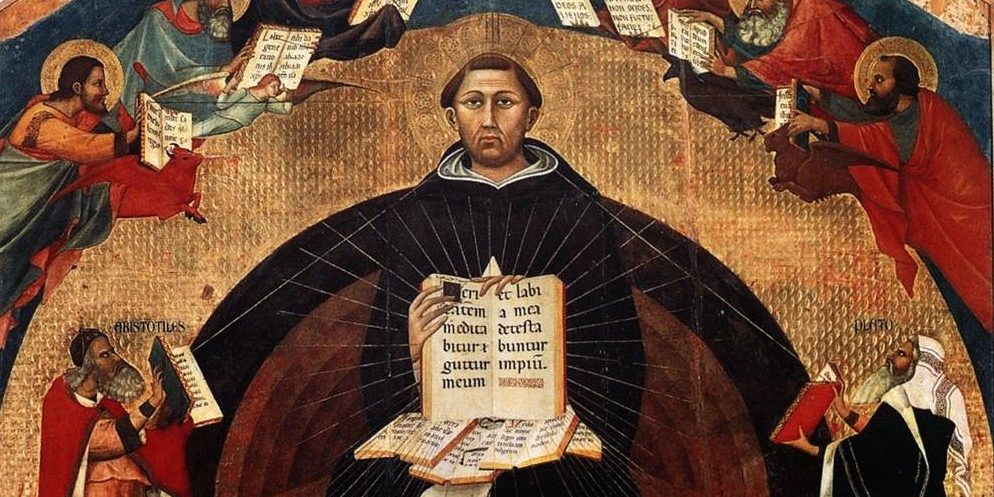

The early church fathers weren’t Hellenistic philosophers who lacked self-awareness, they were brilliant theologians who were making theological sense out of complex passages of Holy Scripture. Share on XThird, Thomas Aquinas helped me to appreciate the doctrine of divine simplicity afresh. Reading the Summa Theologiae (Prima Pars, Q.3) made me realize that I’d only ever heard caricatures of simplicity and that the doctrine was, inter alia, functioning positively to establish the creator-creature distinction.[8] As part of that distinction, I came to appreciate the difference between real and non-real (or logical) relations. With some help from Nicholas of Cusa, I came to see God as not just the being on the top rung of the ontological ladder, but altogether Other. Or, in Thomistic idiom, God is not sui generis, but non generis.

Lastly, Stephen Holmes[9] (again with some help from Aquinas) disabused me of social trinitarianism. I came to appreciate that a trinitarian “person” was not a Cartesian center of consciousness and that the histories of hypostasisand prosopon were intended to serve other purposes. Aquinas gave me the language of “subsistent relation” and I came to appreciate the eternal processions that were properly predicated of the inner life of God.

There were others along the way—too many to mention—who helped me reassemble the pieces that had been shattered by the iconoclasm of my first theology book. More than twenty years later, I’m definitely old enough to drive that new, red sports car; but I wouldn’t recommend it. Instead, I’d recommend something that has been road-tested and proven more reliable—something built to last. I’ve come to appreciate the extent to which the questions and answers of classical and medieval theologians were invaluable resources which ought not to be too hastily discarded. More than that, as a campus minister, I’ve found them to be surprisingly durable and more capable of answering some of the most vexing questions being asked on the campus of the modern, secular university.

[1] Alvin Plantinga, “Self-Profile” in Alvin Plantinga, ed. by James E. Tomberlin and Peter van Inwagen (Dordrecht: D. Reidel, 1985), p. 36.

[2] Paul Gavrilyuk, “Problem of Evil: Ancient Answers and Modern Discontents” in Evil and Creation (Bellington, WA: Lexham Press, 2020), p. 63.

[3] See David Bentley Hart’s excellent treatment of empiricism’s inability to explain these phenomena in The Experience of God: Being, Consciousness, Bliss (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013).

[4] John B. Webster, “Theological Theology” in Confessing God: Essays in Christian Dogmatics II (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2016), pp. 11-32.

[5] Paul Gavrilyuk, The Suffering of the Impassible God: The Dialectics of Patristic Thought (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

[6] Jaroslav Pelikan, Christianity and Classical Culture: The Metamorphosis of Natural Theology in the Christian Encounter with Hellenism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993) and The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, vol 1: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600) (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975).

[7] J. Warren Smith, “Suffering Impassibly: Christ’s Passion in Cyril of Alexandria’s Soteriology” in Pro Ecclesia, XI.4 (Nov. 2002), pp. 463-83.

[8] What Robert Sokolowski has come to call “the distinction”, The God of Faith and Reason: Foundations of Christian Theology (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1995).

[9] Stephen R. Holmes, The Holy Trinity: Understanding God’s Life (Paternoster, 2001).