Why the Nicene Creed?

The new issue of Credo Magazine focuses on the Nicene Creed. The following is an excerpt from one of the issue’s featured articles with Peter Sanlon. Peter Sanlon (PhD) is Director of Training for the Free Church of England. He holds theology degrees from Cambridge and Oxford University. His doctoral research has been published as Augustine’s Theology of Preaching (Fortress Press, 2014) and he is also author of Simply God: Recovering the Classical Trinity (IVP UK, 2014).

The new issue of Credo Magazine focuses on the Nicene Creed. The following is an excerpt from one of the issue’s featured articles with Peter Sanlon. Peter Sanlon (PhD) is Director of Training for the Free Church of England. He holds theology degrees from Cambridge and Oxford University. His doctoral research has been published as Augustine’s Theology of Preaching (Fortress Press, 2014) and he is also author of Simply God: Recovering the Classical Trinity (IVP UK, 2014).

The Church is often weak and prone to listen to the culture’s seductive call. We need help to focus our hearts upon God’s voice. God assists us through means that include the Creeds. Creeds are God’s gift to the Church – arising from listening attentively to God’s Word, the Creeds use liturgical repetition to draw us into deeper experiences of hearing what God really says to the Church. The world uses many powers to arrest our attention – including the power of compulsion. But Creeds have the “authority of the herald, not the magistrate.”[1]

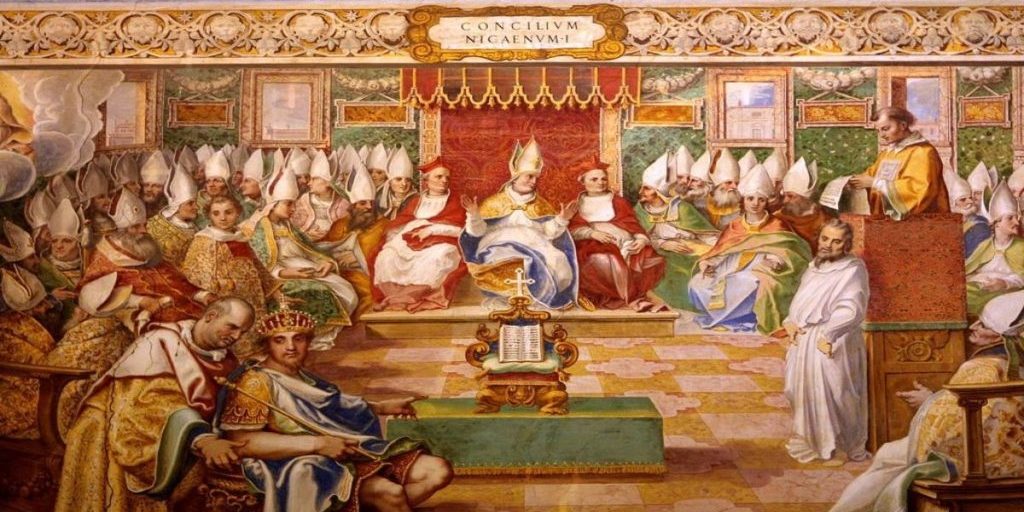

From May to July 325 A.D. the first General Council of the Church was held at Nicaea. Another venue had been considered – the Roman emperor settled on the location in modern Turkey as a convenient place for bishops travelling from around the Roman Empire. Records of the number of bishops in attendance vary – Eusebius suggests more than 250 while Athanasius estimated about 300. The council is significant for both the nature of its deliberations and its pronouncements. The Creed was agreed by a Council; both the statement and process matter.

The Characters

The council was presided over by Constantine, Emperor of Rome. This brought a sense of pomp and the undeniable benefit of “tax exemption”[2] to the gathering. Having sought to bring some measure of unity to the church in the West regarding the Donatist schism, Constantine now wished to foster unity more widely regarding the teaching of Arius. Creeds are God's gift to the Church - arising from listening attentively to God's Word, the Creeds use liturgical repetition to draw us into deeper experiences of hearing what God really says to the Church. Click To Tweet

Constantine sent his top specialist on Church affairs, Bishop Hosius of Córdoba to discern the nature of the theological dispute. Like all good politicians, Constantine knew he could not be an expert on every issue – he deputised capable experts. Córdoba was able to explain that the Church was riven by arguments over the precise way in which God the Son differs from God the Father. Egyptian bishops were excommunicating Palestinian bishops; mobs of church goers from Bithynia were threatening the peace of Galatia. For the peace of his empire, Constantine called a council.

Before the emperor arrived to formally open proceedings, bishops met for a few days to discuss. At the conclusion of proceedings Constantine provided a banquet and lavish gifts to the bishops. The concerns of Constantine were doubtless different to those of the bishops on both sides of the theological debates. It is difficult to evaluate where Constantine’s political concerns ended and theological convictions began. Many bishops bore the gruesome scars from torture in the earlier Great Persecution. The opinions of such “confessors” were highly valued. Bishops who had been tortured under one Emperor, now were applauded by another as they debated fine points of trinitarian theology. The ironies of God’s providence and the suffering triumphs of his Church were on display.

Arius was a charismatic celebrity preacher. He sought to communicate his understanding of Christianity by popular songs. Rowan Williams observed that Arius’s aim was “to develop a biblically-based and rationally consistent catechesis.”[3] In pubs and at workplaces, people sang his theology. The problem was that church ministers and bishops were divided over the faithfulness of Arian doctrine. Arius elicited sympathy, “We are persecuted because we say ‘The Son has a beginning.”[4] He even cited scripture to defend his view. “Surely the Son came ‘from Him’ (Rom. 11:36) and the Son said ‘I came from the Father’ (Jn. 16:28).”[5]

Supporters of Arius’s outlook included Eusebius of Nicomedia and Eusebius of Caesarea. The former gave one of the first speeches at Nicaea – proposing an Arian statement of faith. It was rejected. The latter became famous for his highly valued Church History. He was a much loved bishop. He had “a lack of clearness in doctrine but was constantly a peacemaker.”[6] He thought the Nicene Creed led to Sabellianism, and though he signed the Creed at the behest of Constantine, he never used its language in any subsequent writings. He was pained to be viewed by many as a heretic because he had been censured at the earlier more localised Synod of Antioch. So Eusebius of Caesarea shared his own statement of faith which aimed to unite the divided parties. This also fell flat. Excommunicating those who dissented from the Creed shows how seriously the church should take intellectual sins. Click To Tweet

One observer of the pivotal moment in Church history was Athanasius – at the time the young assistant to the Bishop of Alexandria. Twenty-five years later Athanasius was still defending and elaborating the Nicene Creed. He noted ruefully that the councillor proceedings were “torturous and laborious.”[7]

When Nicaea concluded, only Arius and two bishops – Secundus of Ptolemais and Theonas of Marmarcia refused to sign the Creed that emerged. They were excommunicated and banished to Illyria. As soldiers transported them to their new existence, the majority of bishops tucked into the celebratory feast provided by Constantine, and collected the munificent gifts he gave those who upheld church unity. Excommunicating those who dissented from the Creed shows how seriously the church should take intellectual sins.

Within a few months some signatories, such as Eusebius of Nicomedia, were sent to join the Arian exiles. Embarrassingly, Bishop Theognis of Nicaea was one of those declared to be a heretic by virtue of the Creed agreed in his own city. He was exiled after the council concluded, but returned to office three years later, as local Arian power bases resurged. So the meaning and significance of the Nicene Creed continued to be debated for the rest of the 4th century, only in time settling in the hearts and minds of orthodox theologians as one of the foundational insights into the Faith.

**Read the remainder of Peter Sanlon’s article in the latest issue of Credo Magazine.

Endnotes

[1] John Webster, “Confession & Confessions,” in Nicene Christianity: The Future for a New Ecumenism, ed. Christopher R. Seitz (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2004), 130.

[2] Andrew Louth, “Conciliar Records and Canons,” in The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature, ed. F. Young, L. Ayres, A. Louth (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 394.

[3] Rowan Williams, Arius: Heresy and Tradition (Kindle Location 1459). Kindle Edition.

[4] Arius’s Letter to Eusebius of Nicomedia, §5

[5] Arius’s Letter to Alexander of Alexandria, §5.

[6] O. Bardenhewer, Patrology, 245.

[7] Athanasius, De Decretis.