Jerome Zanchi: Our Forgotten Scholastic Forefather

I remember the first time I heard the term “Scholasticism.” It was spoken as if it were the boogeyman of Roman Catholicism, the monster under the bed that undermined the five solas of the Reformation. It was presented as a relic of the Roman Catholic Church from the Middle Ages that the Reformers had to expel from their midst—lest they fall back into bondage to Rome. It was treated like a sightseeing boat tour crossing the Tiber River for modern Protestants who were too sophisticated to swim it outright.

remember the first time I heard the term “Scholasticism.” It was spoken as if it were the boogeyman of Roman Catholicism, the monster under the bed that undermined the five solas of the Reformation. It was presented as a relic of the Roman Catholic Church from the Middle Ages that the Reformers had to expel from their midst—lest they fall back into bondage to Rome. It was treated like a sightseeing boat tour crossing the Tiber River for modern Protestants who were too sophisticated to swim it outright.

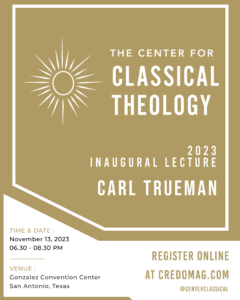

It wasn’t until much later that I realized that these mischaracterizations kept me from growing theologically. I’d embraced the conclusions of men that I trusted to have studied the issue thoroughly, and it wasn’t until much later that I realized they hadn’t read enough to substantiate their pejorative use of the term “Scholasticism.” I realized how gravely mistaken I had been after being pushed to learn about Scholasticism for myself and checking out a book from the library, Protestant Scholasticism: Essays in Reassessment, edited by Carl R. Trueman and R. Scott Clark.[1] I’d embraced the conclusions of men that I trusted to have studied Scholasticism thoroughly, only to realize they hadn’t read enough to substantiate their pejorative use of the term. Share on X

It was through this adventure of recovering Scholasticism for myself that I recognized the gold yielded by much of the Scholastic method. It had been easy for me to believe the mischaracterization of Scholasticism by picking random (or even heretical) statements from Scholastic authors, lumping them all together, and thereby vilifying the Scholastics in toto. This recovery in my own studies helped me realize the futile nature of such an exercise.

While many men were content gathering dross regarding Scholasticism, I felt I had uncovered pure gold. I discovered the amazing potential for precision offered by the Scholastic method. It had the ability to help me communicate the core truths of the Christian faith in a more robust and technical way so as to refute a host of errors. With that in mind, I’d like to briefly explain what Scholasticism is (and what it is not), review the appropriation of this method by the stalwart Protestant minister Jerome Zanchi, and then consider how the Scholastic method can aid us today.

What is Scholasticism?

Scholasticism is a term used to describe a method that structured a system of thought, a method that has had a significant impact on both theology and philosophy. The head of a Christian school in the sixth century was commonly referred to as a scholasticus (which means “scholar”). Thus the term developed out of that educational setting.[2] No matter where you look to define Scholasticism, you find a common theme: “The term ‘scholasticism,’ thus should not be much associated with content but with method, an academic form of argumentation and disputation.”[3] Ryan McGraw helpfully summarizes the benefits of the Scholastic method in that it “promotes precision and clarity in teaching,” “enable[s] ministers and seminary professors to translate academic theology into pastoral theology,” and “promotes historical methodology,” which in turn yields, for the judicious student, a recovery of “Reformed theological method and not merely Reformed theological content.”[4] Most helpfully, he summarized, “Scholasticism referred decisively to an educational model. As such, scholasticism was a tool, or rather a set of tools, that was most immediately relevant for the purpose of training Reformed pastors.”[5] If Scholasticism is not content but method, what is the method and how did we get it? Furthermore, why is it useful for the prudent student of Scripture? Scholasticism is a term used to describe a system of thought that has had a significant impact on both theology and philosophy. Share on X

Scholasticism is a method of learning that was formalized in medieval Europe between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries. It combines logic, metaphysics, and semantics (or rhetoric) to form a single discipline, and is widely regarded as having made significant contributions to the thoughtful and precise development of Christian thought. It’s essentially a tool and method for learning that emphasizes dialectical reasoning. This involves the exchange of arguments (or theses) and counterarguments (or antitheses) to arrive at a conclusion or synthesis (formally known as dialectic reasoning). In medieval Europe, dialectics was one of the three original liberal arts, along with rhetoric and grammar, collectively known as the “trivium.”[6]

During the period of Scholasticism, there were two primary methods of teaching. The first, known as the lectio, involved a teacher simply reading a text and explaining certain concepts or words. However, no questions were allowed. The second method, the disputatio, was a more interactive approach where a question would either be announced beforehand or proposed by students.[7] The teacher would then provide a response, citing authoritative texts, such as the Bible, to support their position. Students would then offer counter-arguments, and the debate would continue back and forth, with someone taking notes to summarize the discussion. These became known as disputations. The goal of a disputation was to resolve a question or contradiction related to theology or philosophy, and it was a key aspect of formal scholastic training in the church during the medieval period. Disputations provided several benefits in scholastic training. First, they allowed students to practice the art of argumentation and refine their skills in logical reasoning. Second, they provided a forum for the presentation and critique of ideas, and in doing so, helped to advance knowledge in a particular field of study. Third, they allowed students to engage with authoritative texts, such as the Bible, and to develop their ability to support arguments with evidence. Finally, disputations were used as a means of testing students’ knowledge and understanding of a particular subject, often in preparation for their formal examinations.[8]

In the thirteenth century, Scholasticism made two very decided advancements. First, the use of reason in the discussion of spiritual truth and the application of dialectic to theology were accepted without protest, so long as they were kept within the bounds of moderation. Second, there was a willingness on the part of the schoolmen to go outside the lines of strict ecclesiastical tradition to learn from Aristotle and many others. Scholasticism had the ability to help me communicate the core truths of the Christian faith in a more robust and technical way so as to refute a host of errors. Share on X

Late Scholasticism, which began in the fourteenth century, became increasingly intricate and sophisticated in its differentiation and reasoning. It gave rise to specific branches of thought, such as Thomism and Scotism, which follow the philosophies of Thomas Aquinas and John Duns Scotus, respectively.[9] Both methods differ in their emphasis on reason and intuition, as well as in their approach to theology. However, during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Scholasticism was superseded by Humanism and began to be regarded as a rigid, formal, and antiquated approach to philosophy.

Based on that historical background, how would we identify something that uses the Scholastic method? Richard Muller helpfully provides a few significant features in identifying something as Scholastic. The characteristics that unify the Scholastic method are 1) identifying an ordered argument suitable for technical, academic discourse, 2) presenting a thesis or question, 3) organizing it in a way that makes discussion or debate simpler, 4) acknowledging potential objections to the proposed answer, 5) providing a formulation of the thesis with respect to known sources, and 6) providing a response to all objections.[10]

Did the Reformers Reject Scholasticism?

The theology of Reformed Scholasticism has often been overlooked in favor of the theology of the great Reformers, despite the assistance the former gave to the latter. While those who initiated the Protestant Reformation are often celebrated, the theologians of the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries who codified and perpetuated the movement are seldom given the same level of attention. Yet, those who continued the movement deserve recognition for their contributions as well. They defended, systematized, and formalized over the course of a century and a half what the Reformation began in less than half a century. The Reformation would be incomplete without the confessional and doctrinal codification that Reformed orthodoxy provided. In fact, without a normative and defensible body of doctrine, embodied in the confessions to establish guardrails of orthodoxy, Protestantism would not have been able to withstand the onslaught of errors presented by groups such as Catholics, Spiritualists, rogue Anabaptists, Socinians, Arminians, and others. Therefore, neglecting the contributions of these individuals is unjustified. The theology of Reformed Scholasticism has often been overlooked in favor of the theology of the great Reformers, despite the assistance the former gave to the latter. Share on X

Perhaps this neglect stems from a misunderstanding of the critical parts of Calvin’s Institutes regarding the “schoolmen,” or Luther’s criticisms in which he targets a specific formulation of Scholasticism in Scotism. Interestingly enough, Luther never mentions Lombard or Aquinas in those criticisms.[11] This is not to say that the preeminent Reformers agreed with those they didn’t criticize, but it should be a cautionary tale of the genetic fallacy: they didn’t reject the Scholastic method altogether just because they rejected certain doctrinal conclusions of some Scholastics. In fact, their students and theological grandchildren would go on to leverage the method in order to articulate the doctrines of the Reformation more precisely.

The Reformed Scholastic theologians played a crucial role in the history of Protestantism by creating an institutional theology (reaching its zenith in the Puritans) that was both confessionally in line with the Reformation and doctrinally continuous with the larger tradition of the Church. While the Reformers had developed a series of doctrinal issues based on their scriptural exegesis, the orthodox theologians held firmly to these insights and the confessional norms of Protestantism, while simultaneously working toward the establishment of a body of “right teaching” that was in continuity with sound Christian thought. In order for Protestantism to be representative of the Church, the Reformation’s witness had to reform not only ecclesiastical abuses (such as indulgences), but also errors related to doctrine (such as the Roman denial of Sola Fide). As such, later generations of Reformed Scholastics had to transcend the selectivity of the Reformation’s polemic in order to present a whole body of doctrine. Later generations of Reformed Scholastics had to transcend the selectivity of the Reformation’s polemic in order to present a whole body of doctrine. Share on X

Upon closer examination, Reformed orthodoxy, and Reformed Scholasticism in particular, can be recognized as a distinct form of Protestant theology that has both similarities with, and differences from, the theology of the Reformation. Although it is rooted in the theological convictions of the Reformers, it developed systematically and scholastically in a way that diverged from the methods of the Reformation, often relying upon forms and methods from the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries.

The influence of Reformed Scholasticism is still evident in contemporary Protestantism, and is necessary for understanding this theology and its relationship with earlier ages, particularly when it comes to the Middle Ages and the Reformation. While some major changes have occurred, orthodox or Reformed Scholastic theology is still evident in the works of Charles Hodge, Archibald Alexander Hodge, and Louis Berkhof, with little alteration in terms of its formal and substantial dogma. Charles Hodge’s Systematic Theology, for example, is indebted to Francis Turretin’s Institutes of Elenctic Theology —though it seeks to present orthodoxy’s systematic insights in a nineteenth-century mold, especially in its prolegomena.[12]