Remembering Steinmetz, remembering the Reformation (Matthew Barrett)

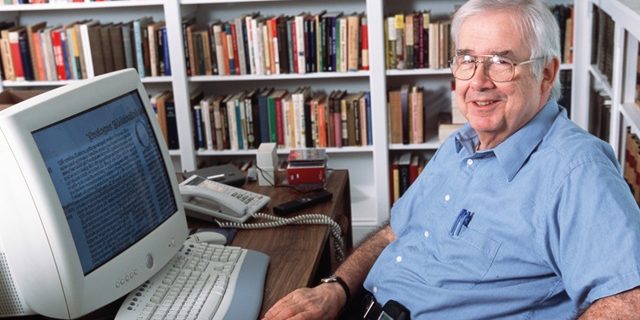

This past November, Thanksgiving Day in fact, David Steinmetz (1936-2015) died at the age of 79. My guess is that many readers may not know who he was. A shame. He is an author one should know, especially for those interested in Reformation theology, Steinmetz’s area of expertise. Let me, then, say a little about him.

He was a native of Ohio and majored in English at Wheaton College. He then went to seminary at Drew University only to achieve a ThD from Harvard in 1967 under renown medieval and Reformation scholar Heiko Oberman.

Eventually he ended up at Duke Divinity School where he taught for over 35 years, retiring in 2009. Steinmetz was one of the leading Reformation scholars of our time. He took after his own teacher, Heiko Oberman, and his legacy can be seen not merely in his published works but in his students, individuals like Richard Muller, John Thompson, Timothy George, and many others.

As a visiting professor at Harvard, he taught a class (also taught by his mentor Heiko Oberman) called “Calvin and the Reformed Tradition.” One of his students in the late 70s was Timothy George and Steinmetz would end up serving on George’s doctoral committee. In a Christianity Today article George recalls Steinmetz in the classroom as quite brilliant:

He was the best classroom teacher I have ever had. He was not only brilliant, but also passionate and insightful. He never lost sight of the larger context of the texts and traditions he was so adept at bringing to life. I shall never forget his early morning lectures in Andover Hall, as he presented Calvin’s life and thought like a great actor commanding the stage. He never took roll; no one dared miss his lively lectures—replete with chalk-drawn diagrams on the blackboard, lively interrogations of the 16th-century texts, and dramatic enactments of Reformation debates. You felt like you were there with Luther and Zwingli at Marburg, with Calvin and Bolsec in Geneva.

George’s description makes you wish you could have been there!

Steinmetz was also an ordained minister in the United Methodist Church. He was especially clear in a sermon he preached in 1997 to Duke undergraduates that one should not try to be original, inventing one’s own gospel, but rather faithful. And he warned students against the temptation to only preach those parts of Scripture they like, rather than the whole counsel of God.

The good news for the members of the graduating class who plan to enter the ordained ministry is that you don’t have to invent your own gospel. All of the church hopes you will be imaginative and resourceful. It doesn’t expect you to be original. Actually, it rather discourages originality with respect to core convictions. The church will authorize you to preach an ancient gospel you didn’t cook up and that is true whether you believe it or not. You will be commissioned by bishops and elders who have done it before you to preach the whole counsel of God, including the awkward bits we don’t understand very well. What you will not be ordained to do (though some of you will yield to the temptation to do it anyway) is to preach only those parts of the Christian tradition you have found personally meaningful. God doesn’t intend to mold the church in your image, you’ll be relieved to know, but in the image of the crucified and risen Christ.

If you are interested in reading Steinmetz, here are a handful of resources I would recommend:

“The Superiority of Precritical Exegesis” in Theology Today

George explains what this ground-breaking article was all about:

He offered a frontal assault on what C. S. Lewis—one of Steinmetz’s favorite authors—once called the “chronological snobbery” of scholarly methods that dismiss as antiquated traditional ways of reading the Bible. Returning to Augustine and the early church, Steinmetz showed how the “fourfold sense of Scripture” that became widely used in the Middle Ages was a way of taking seriously the words and sayings of Scripture, including implicit meanings beyond the original intentions of the human authors. This did not mean abandoning the primacy of the “literal sense” of the text, an emphasis already found in Thomas Aquinas. But it did mean recognizing the increasing complexity of the “literal sense” which in the Reformation absorbed more and more of the content of the spiritual meanings.

Much of what is known today as the “theological interpretation of Scripture” proceeds from assumptions clarified by Steinmetz. A new generation of scholars has come to see the interpretive tradition of the church not as a problem to be overcome, but rather as an indispensable aid for rightly understanding the inspired Word. As Steinmetz once said in my hearing, sola Scriptura does not mean nuda Scriptura but rather prima Scriptura—not Scripture only but Scripture asthenorm by which all other writings and teachings are judged.

“This attractive collection . . . blends careful, current scholarship with an eminently readable style to create an enlightening guide to Martin Luther’s religious thought.”–Journal of Religion

Luther in Context places Martin Luther within his theological world–a world in which he engaged in intellectual dialogue with key thinkers including Plato, Augustine, Calvin, William of Ockham, and Biel. These essays cast light on Luther’s thought by positioning it within the context of his theological antecedents and contemporaries. A leading scholar of Luther studies, David Steinmetz both seeks out Luther’s new ground and demonstrates where the Reformer remained Augustinian or Ockhamist.

Steinmetz explores many issues that were of considerable importance to Luther, including temptation, the hiddenness of God, and justification by faith alone. Although it is not intended to be a complete presentation of Luther’s thought, this book does examine a wide range of themes and problems in Luther’s theology. Thus, a reader who is encountering Luther for the first time will find a broad sampling of the ideas that were especially important to the Reformer.

This expanded edition contains three additional essays, one of which is appearing in English for the first time. “Luther and Calvin on the Banks of the Jabbok” contrasts Luther and Calvin as biblical commentators by comparing their handling of Genesis 32. “Luther and the Ascent of Jacob’s Ladder” examines the late medieval exegetical tradition surrounding Jacob’s dream and Luther’s relationship to that tradition. Finally, “Luther and Formation in Faith” traces the reeducation of Latin Christendom in a Christian faith and practice shaped by the theology of Luther.

Students and scholars of the Reformation will find Luther in Context to be an insightful glimpse into the thought and theology of Martin Luther.

Calvin in Context: Second Edition

The book illuminates Calvin’s thought by placing it in the context of the theological and exegetical traditions–ancient, medieval, and contemporary– that formed it and contributed to its particular texture. Steinmetz addresses a range of issues almost as wide as the Reformation itself, including the knowledge of God, the problem of iconoclasm, the doctrines of justification and predestination, and the role of the state and the civil magistrate. Along the way, Steinmetz also clarifies the substance of Calvin’s quarrels with Lutherans, Catholics, Anabaptists, and assorted radicals from Ochino to Sozzini. For the new edition he has added a new Preface and four new chapters based on recent published and unpublished essays. An accessible yet authoritative general introduction to Calvin’s thought, Calvin in Context engages a much wider range of primary sources than the standard introductions. It provides a context for understanding Calvin not from secondary literature about the later middle ages and Renaissance, but from the writings of Calvin’s own contemporaries and the rich sources from which they drew.

Reformers in the Wings: From Geiler von Kaysersberg to Theodore Beza

This book offers portraits of twenty of the secondary theologians of the Reformation period. In addition to describing a particular theologian, each portrait explores one problem in 16th-century Christian thought. Catholic, Lutheran, Reformed, and Radical thinkers are all represented in this volume, which serves as both an introduction to the field and a handy reference for scholars.

Taking the Long View: Christian Theology in Historical Perspective

Taking the Long View argues in a series of engagingly written essays that remembering the past is essential for men and women who want to function effectively in the present-for without some knowledge of their own past, neither individuals nor institutions know where they have been or where they are going. The book illustrates its thesis with tough-minded examples from the Church’s life and thought, ranging from more abstract problems like the theoretical role of historical criticism to such painfully concrete issues as the commandment of Jesus to forgive unforgivable wrongs.

Also, two others worth your time include:

The Cambridge Companion to Reformation Theology (Cambridge Companions to Religion)

Matthew Barrett is Tutor of Systematic Theology and Church History at Oak Hill Theological College in London, as well as the founder and executive editor of Credo Magazine. Barrett is the author of numerous book reviews and articles in academic and popular journals and magazines. He is the author of several books, including Salvation by Grace: The Case for Effectual Calling and Regeneration, Owen on the Christian Life: Living for the Glory of God in Christ (Theologians on the Christian Life), God’s Word Alone: The Authority of Scripture. Currently he is the series editor of The 5 Solas Series with Zondervan. You can read more about Barrett at matthewmbarrett.com.

Luther in Context

Luther in Context