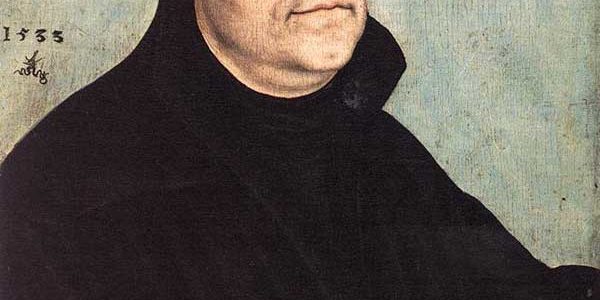

Martin Luther: Visionary Reformer (review by Matthew Barrett)

Recently I contributed a review to the Oxford University Press’s The Journal of Theological Studies. The book under review? Scott H. Hendrix’s Martin Luther: Visionary Reformer (Yale University Press, 2015). The review is now available at OUP where you can also download it as a pdf. Here is what I had to say:

Recently I contributed a review to the Oxford University Press’s The Journal of Theological Studies. The book under review? Scott H. Hendrix’s Martin Luther: Visionary Reformer (Yale University Press, 2015). The review is now available at OUP where you can also download it as a pdf. Here is what I had to say:

The year 2017 certainly is the year for publications on the life and theology of Martin Luther. Already we are witnessing legions of books, each trying to claim our attention, resurrecting Luther for the twenty-first century. The danger in such publishing endeavours, as well intentioned as they may be, is to hijack Luther for our own agendas, making him say what we want him to say, or at least what we feel is most relevant for our readers. Students of the Reformation may be fearful, therefore, to pick up any number of Luther biographies, unsure whether the real Luther will be presented or not.

Readers with such fears will be relieved to receive this new biography by one of the most respected Luther scholars of our day, Scott H. Hendrix, Emeritus Professor of Reformation History, Princeton Theological Seminary. In the past Hendrix has proven himself a reliable source, who sheds invaluable light not only on Luther but the medieval context in which Luther was situated. Previous publications, such as Luther and the Papacy (1981), demonstrate this much. In this new study the many strengths of Hendrix’s prior research come together, even work together, to give us Luther the visionary reformer.

Unquestionably, one of the major strengths of Hendrix’s research is his attention to Luther as a medieval Christian and theologian. In chapter 3, ‘Holy from Head to Toe, 1501–1511, Erfurt–Wittenberg’, Hendrix is strategic, introducing readers to William Ockham and Gabriel Biel, the complex relationship between the late medieval monastery and university, and the matrix of the penance system, each of which proves significant to the events leading up to Luther’s posting of the 95 theses. For example, Hendrix is especially illuminating when he reminds us that Luther was first introduced to the soteriology of Biel by John Nathin, one of Luther’s professors. Nathin, who may have even heard some of Biel’s sermons, would place Biel’s commentary on the canon in Luther’s hands. Historical details that at first glance seem irrelevant eventually show themselves to be pillars in the evolution of Luther’s own theology. Hendrix demonstrates how Luther, by 1516, had a change of mind, and was no longer sympathetic to Biel’s ordo salutis. He had now been convinced to return to a more Augustinian view of grace, a move that would become readily explicit in his Heidelberg Disputation. Hendrix’s biography, in other words, is full of historical insights like this one, helping readers understand in what ways Luther’s theology developed and why the Reformation took form the way it did.

Hendrix must also be commended for his historical and theological clarity, a trait other Luther biographies sometimes lack in abundance. Rarely have I seen the narrative concerning Luther’s reaction to the system of penance and indulgences retold with such perspicuity. Particularly refreshing is the way Hendrix keeps Luther’s rejoinder in proper balance. It is becoming more and more common for historians to downplay the 95 theses, as if their accidental success and academic nature somehow mean Luther unintentionally, and perhaps stoically, stumbled across the Achilles heel of Rome. Hendrix reminds us, however, that Luther’s irritation was already building, and perhaps at the breaking point. On the one hand, we should not think of 31 October 1517 as if a revolutionary marched to the door with a hammer, calling upon his comrades to join him. On the other hand, we should not swing the pendulum; the 95 theses were not the first time Luther took issue with the abuses he witnessed, nor would they be the last. Luther was on the road to Reformation already by 1517, even if he was not yet aware just how steep that road would become in the months and years that followed.

Yet perhaps the most important contribution Hendrix makes has to do with defining Luther’s Reformation itself. Countless publications today attribute the Reformation’s success to social, political, and cultural factors. There is truth to such studies; the Reformation was very much a product of its day. A study of the political manoeuvres of the sixteenth century and how those manoeuvres aligned serendipitously with Luther’s theological advances prompts all historians to consider just how conditioned Luther’s reform was upon political decisions. Nevertheless, Hendrix takes us back to a more fundamental cause: the Reformation was about the gospel. Luther once said in a letter to Staupitz (31 March 1518), ‘I teach that people should put their trust in nothing but Jesus Christ alone, not in their prayers, merits, or their good deeds’ (WABr 1, 160). Here, says Hendrix, is the ‘essence of his reforming agenda’ (p. 68). Hendrix is right; according to Luther, the Reformation he devoted his life to may have had many characteristics, but its essence was sola fide and solus Christus.

Are there shortcomings to Hendrix’s study? Some. The sections where he addresses Luther’s conflict with Zwingli, as well as his view of the Lord’s Supper at large, could have been improved if Hendrix had explored the type of Christology Luther presupposed in such debates. I fear students of the Reformation read about Luther’s view of the Supper and assume that merely a hermeneutical issue is at play. However, theologians of the Reformation will readily acknowledge that behind the Lutheran view of the Supper sits a specific interpretation of the communicatio idiomatum, an interpretation that Calvin and his disciples would not be slow to counter. At times, in other words, Hendrix could have probed deeper still into aspects of Luther’s theological rationale.

In the end, Scott Hendrix has written a biography that is not, thankfully, distracted by countless twenty-first century agendas. Instead, he strives to let Luther speak. That may sound basic to anyone writing history, but unfortunately it can no longer be taken for granted, especially in the year 2017 when Luther biographies abound.

Matthew Barrett (PhD, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary) is tutor of systematic theology and church history at Oak Hill Theological College in London, as well as the founder and executive editor of Credo Magazine. He is the author of several books, including Salvation by Grace (P&R, 2013), Owen on the Christian Life (Crossway, 2015), God’s Word Alone: The Authority of Scripture (Zondervan, 2016), and Reformation Theology: A Systematic Summary (Crossway, 2017). Currently he is the series editor of The 5 Solas Series with Zondervan. You can read more at MatthewMBarrett.com.