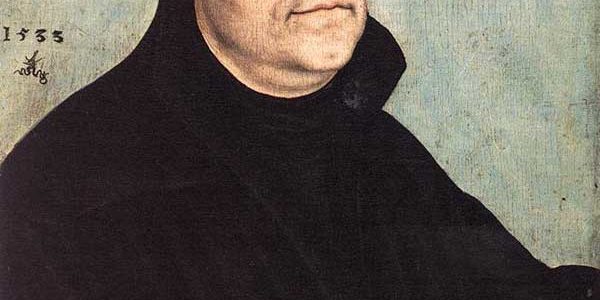

The Luther Treasure Trove (Matthew Barrett)

Theological and historical dictionaries can be, ironically, terribly unhelpful. Too often they are kept on the shelf in that rare chance that they might be consulted. When they are consulted, the reader is left with such a basic introduction to the topic investigated that there are far more questions than answers. And so they collect dust, taking up a large portion of bookshelf space.

Baker Academic’s colossal Dictionary of Luther and the Lutheran Traditions is a most welcome exception. General editor Timothy J. Wengert, along with a host of Associate Editors (Granquist, Haemig, Kolb, Matters, Strom), have recruited an impressive team of experts to write hundreds of articles introducing readers to the rich and deep well of Luther scholarship. Frankly, this collection of articles is pleasantly overwhelming. As a theologian and historian of the Reformation, I would describe the experience to a BBQ lover discovering Kansas City. What may have been a 15 minute pit stop to refill the tank turns into an extended lunch over mouthwatering, juicy BBQ.

Baker Academic’s colossal Dictionary of Luther and the Lutheran Traditions is a most welcome exception. General editor Timothy J. Wengert, along with a host of Associate Editors (Granquist, Haemig, Kolb, Matters, Strom), have recruited an impressive team of experts to write hundreds of articles introducing readers to the rich and deep well of Luther scholarship. Frankly, this collection of articles is pleasantly overwhelming. As a theologian and historian of the Reformation, I would describe the experience to a BBQ lover discovering Kansas City. What may have been a 15 minute pit stop to refill the tank turns into an extended lunch over mouthwatering, juicy BBQ.

The Dictionary is impressive for a variety of reasons. Not only are the traditional Luther/Lutheran topics covered, but a slew of articles put forward the influence and legacy of this tradition as well. In other words, while the title may give the impression that the Dictionary will be occupied with denominational history, articles are devoted to sometimes the most surprising and fascinating of topics, such as the influence of Luther on the American Civil War, the use of the Fathers in Luther/Lutheran thought, or the heritage of music left behind (and retrieved yet again) by Lutheran musicians. Noticeable, and to the credit of the editors, is the strong emphasis throughout on the global influence and success of Luther’s thought. I found this emphasis a correction. Evangelicals today are painfully unfamiliar with Luther and the Lutheran tradition, assuming it has had little impact in recent centuries. Not true. Dozens of articles remind readers that a worldwide impact has resulted, as the ideas of the Lutheran tradition spread across Europe and even Latin America.

Yet as a theologian I was naturally drawn to those articles dogmatic in nature. A word to fellow theologians: this Dictionary turns out to be a meal. Honestly, I was worried going into the volume. Since the Enlightenment and the rise of Protestant Liberalism, many German Lutherans have painted a very different picture of Luther’s theology than first affirmed by his followers in the immediate decades after Luther’s death. However, many articles countered misconceptions and misinterpretations of Luther with applaudable historical and theological acumen.

For example, take Mark C. Mattes article on justification. Mattes fearlessly pushes back against Ritschl, Harnack, Holl, Mannermaa, and others in order to demonstrate the forensic nature of Luther’s doctrines of justification and union with Christ. I particularly appreciated how Mattes exposed the thesis that aims to blame Melanchthon for the forensic invention of imputation, as if such a doctrine was foreign to Luther. Mattes also insightfully observes how Holl fails to account for how Luther’s early stance developed into his more mature, forensic view of justification. Mattes reminds us that historical context matters; Luther’s theology was developing and we dare not take his early years as definitive when Luther’s mature thought was yet to come. Theological conclusions hang on the historical narrative.

I should also praise Mattes for the way he stresses the efficacy of the Word, an emphasis more and more Luther scholars appear to be acknowledging. “The justifying verdict is a performative word that does what it says and says what it does,” notes Mattes. The implication? “Hence the attempt to pit a forensic approach, ‘being declared righteous,’ against an effective approach, ‘being made righteous,’ does not appropriately apply to Luther.” In other words, Luther’s “forensic approach conveys a specific effect since the justifying word is a verdict that simultaneously kills sinners and makes them alive.” Mattes, in short, counters Ritschl and Holl who attempt to “disassociate Luther from a forensic approach to justification, fearing that it is implausible, a legal fiction, needing ethical or ontological supplementation or warrant.” No legal fiction myth here.

Mattes is just as probing in pointing readers to the recent critiques (Mattes, Paulson, Schumacher) of Finnish representatives like Mannermaa. “For Luther, salvation is based not on the indwelling Christ who deifies, but forensically on Christ who died for us.” Then comes Mannermaa’s heavy weight punch: “Mannermaa’s view leads to an unnecessary dilemma: favor is construed as objective while donum is somehow subjective.” Pointing to the objective work of Christ, Mattes writes, “Only on account of this truly objective foundation of imputation as forgiveness for Jesus’s sake is the gift (donum) of the present Christ preached and so given—not to the old creature as old, but to the new creature as the act of new creation itself.” Refusing to set union with Christ over against forensic imputation, Mattes concludes, “Undoubtedly Luther affirmed that the believer is united with Christ in faith. But it is equally clear that for Luther the Christian is justified on the basis of nothing else but Christ’s imputed righteousness.” Perhaps Luther and Calvin are not as different in their doctrine of union with Christ as some would have us believe!

I put Mattes’ article forward to demonstrate that the Dictionary is not only a historian’s playground; it is full of rock climbing walls theologians of any tradition will be eager to ascend. At the top of this mountain not only sits Luther but a host of his theological heirs whose ideas cannot afford being ignored. Granted, climbing this mountain will take work (nearly 900 pages of work!), but with each step the reader seems to discover a new altitude of historical, theological, and cultural insight.

Matthew Barrett (PhD, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary) is Associate Professor of Christian Theology at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, as well as the founder and executive editor of Credo Magazine. He is the author of several books, including Salvation by Grace, Owen on the Christian Life, God’s Word Alone: The Authority of Scripture, and Reformation Theology: A Systematic Summary. Currently he is the series editor of The 5 Solas Series with Zondervan. You can read more at MatthewMBarrett.com.

Matthew Barrett (PhD, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary) is Associate Professor of Christian Theology at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, as well as the founder and executive editor of Credo Magazine. He is the author of several books, including Salvation by Grace, Owen on the Christian Life, God’s Word Alone: The Authority of Scripture, and Reformation Theology: A Systematic Summary. Currently he is the series editor of The 5 Solas Series with Zondervan. You can read more at MatthewMBarrett.com.