Hymns as Poems

Of the nearly sixty books that I have published, the one that I have most relished producing is an anthology of forty classic hymns presented as devotional poems and accompanied by literary analysis. Composing the book was a journey of discovery for me, as well as offering me a platform to assert long-held convictions about the need to hold onto the great tradition of hymnody in the face of a seemingly irresistible trend to displace them with something inferior.

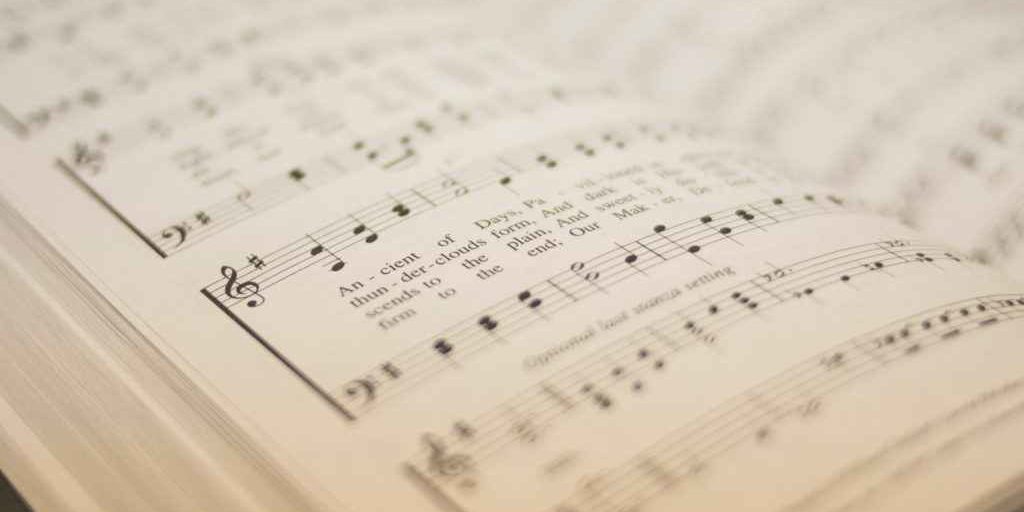

At the very time I was composing my book, I discovered that the practice of printing and reading hymns as poems long preceded our familiar practice of limiting hymns songbooks used mainly in church. That discovery came when I reviewed a University Press book entitled The Hymnal: A Reading History, by Christopher N. Phillips. The author establishes in detail that until the 1870s, hymn books were small, portable, five-by-three inch anthologies of hymn texts (poems) without accompanying music. These books were used daily and carried from home to offices, schools, fields, and markets.

My contact with Phillips’ book came after I had completed my own book, but it was a welcome confirmation that I was on the right track in promoting hymns as devotional poems. Starting in my graduate school days, I have moved into a world of literary scholarship where hymns are acknowledged as a branch of English literature, but the acknowledgment is no more than lip service. Even if hymns appear in anthologies of English literature, they do not make their way onto course syllabi. This is a completely inexcusable slight. Every hymn begins as a poem. Once it exists as a poem, it can go in quest of accompanying music. If the quest is successful, the poem becomes a hymn in addition to a poem. Every hymn begins as a poem. Once it exists as a poem, it can go in quest of accompanying music. If the quest is successful, the poem becomes a hymn in addition to a poem. Click To Tweet

I was confirmed in this belief by the account that Timothy Dudley-Smith gives of his first hymn, which is also his signature hymn. Dudley-Smith shares in his book Lift Every Heart that “Tell Out My Soul” was “not written as a hymn” but as a poem. It became a hymn when it was solicited as a hymn by the editors of the Anglican Hymn Book.

What happens when we read and ponder and analyze hymn texts as poems? My composition of an anthology of hymns with accompanying explications gradually answered that question for me. The most important answer that emerged was that hymnic poems behave just like other poems, and especially like devotional poems authored by poets such as Donne, Herbert, and Milton. As I look back over my career, I can see that the “lip service” syndrome in my own discipline of literary studies has done hymns a great disservice. It creates a false illusion of having done justice to a branch of English poetry, thereby preventing scholars from actually delving into it.

My reclamation project uncovered how revolutionary it is to deal with hymns printed in sequence as poems, with each stanza following its predecessor. In the format of our hymnbooks, each stanza begins at the same point, under the preceding stanza(s). A circular model inevitably dominates, with each stanza being in some sense a rerun of the previous one. When we see the text printed in linear fashion, one of the most important qualities of a poem immediately takes shape in our awareness, namely, the organic progression of thought and feeling that comprises every good poem.

Along with this progression of one unit leading to the next in a coherent and growing way, the principle of theme and variation becomes apparent. That framework describes how every carefully constructed poem has a unifying center from which everything else radiates, with individual stanzas (usually) become separate variations on the central theme.

Other common features of poetry also appear in hymnic poems. Verbal beauty is one of the most prominent of these features. Very few of the authors of our classic hymns were viewed by themselves and others as poets. Many of them were busy clergymen. Others were obscure people. The biographies of hymn writers reveal that many of our great hymns came out of experiences of great suffering and loss. Where, then, does the unfailing eloquence and aphoristic phrasing and beautiful wording and imagery of great hymns come from? My own conclusion is that these things fell as a benediction from God on poets of the common people. We should not relinquish the honored term poets for these people, because they were poets in full command of their craft.

In addition to the overriding quality of verbal beauty, we can also see other common elements of poetic texture (the literary term) in hymnic poems. The most prevalent by far is allusion, and specifically, allusions to the Bible. Hymnic poems are saturated with biblical allusions. Hymnic poems draw upon the great archetypes of life and literature—master images and motifs like the river and the city and the penitent and suppliant. Nature imagery figures prominently. In all of these techniques, hymnic poems lend themselves to exactly the same type of explications that I conduct with English poetry in my classroom.

The only qualification I would make is that hymnic poems represent poetry under vows of renunciation (a formula bequeathed by a towering hymnist of an earlier era named Eric Routley). What this means is that writers of hymnic poems avoid the complex techniques and subtle effects that characterize the poems that customarily get taught in college literature courses. Hymnic poems are truly poetic, capable of eliciting my best efforts as a professional literary scholar, but they represent poetry for the common person.

A natural question remains to be answered: Where does this leave us in regard to the future of hymns in our individual and church lives? One answer is that we need to open a treasure chest that has been locked for a very long time. A vast repository of devotional poetry is just waiting to be tapped. Everyone can become a reader of devotional poetry in the form of hymns considered as poems.

But we need to do more than read the classic hymns as devotional poems. We must also sing them. Literary analysis shows what treasures they are. It should be unthinkable that the church in our day would allow this treasure to sink into oblivion. Those who are no longer familiar with the hymns of the past can be taught to sing and love them, just as they rise to the occasion when learning a newly-minted contemporary song. It is not asking too much of ministers and worship leaders that every contemporary song in a worship service is balanced by a hymn from the past.