The Gospel-Centeredness of Robert Moffat’s Mission

“[The missionary] knows full well that, if he wishes to save souls, he must preach Christ, the power of God and the wisdom of God, without which all of his efforts to save souls must be like the sounding brass and tinkling cymbal” (Robert Moffat).

In both Christian and secular circles, David Livingstone is the most notorious missionary to ever step foot in Africa, so it’s rather common for Livingstone’s shadow to be cast over a man who served there long before him – his father-in-law, Robert Moffat. Moreover, when it comes to each of their missions, Moffat’s was much more prioritist in nature than Livingstone’s holistic– or dare one say, liberationist– mission.[1] Toward the end of his life, Livingstone’s primary motivation became the liberation of the oppressed slave. While this was a noble cause, some say that Livingstone unfortunately moved away from regular, intentional, evangelistic practices. Jay Milbrandt writes:

Missionaries passionately claimed him. But was he a missionary? Despite unapologetically resigning his missionary post, Livingstone was imagined by the world as proselytizing Africans by the thousands. Yet, his converts to Christianity numbered only one – and now even this singular believer had relapsed into animism.[2]

Milbrandt believes that if Livingstone “pursued one purpose, it was the abolishment of the African slave trade.”[3] This observation is not noted to downplay the significance of Livingstone’s life and work, but it does bring up a relevant question: what makes one a missionary? Quite contrary to his son-in-law, Robert Moffat consistently saw his primary goal as the proclamation of the gospel. All other work took a backseat to this.

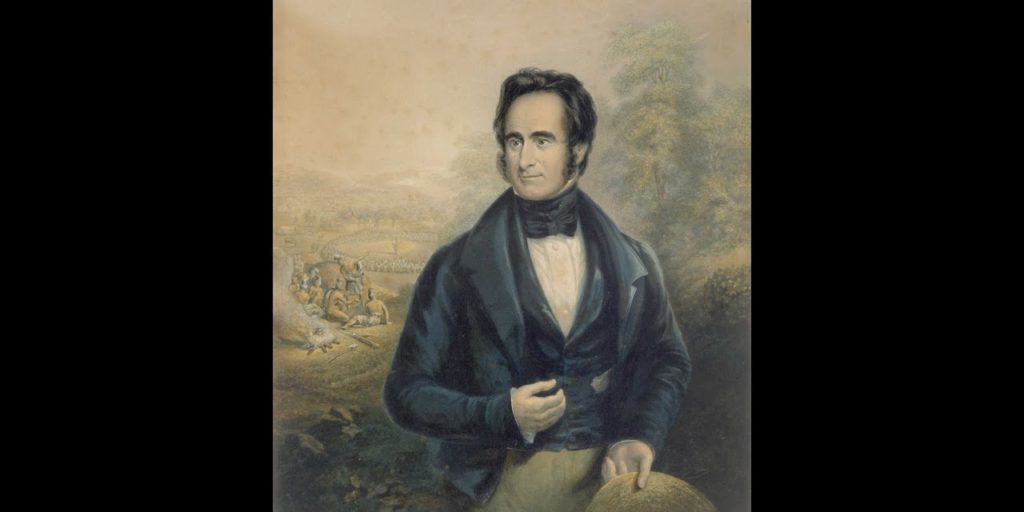

So, who was Robert Moffat? He is a man “sometimes regarded as the patriarch of South African missions.”[4] Moffat was to Africa what William Carey was to India and Robert Morrison to China. Before leaving to serve with the London Missionary Society, Moffat worked for James Smith, a Scottish merchant in Manchester, England. At some point, he experienced the missionary call. In 1817 – when David Livingstone was just a toddler – Moffat set sail for Africa, the continent to which he would give his life. Though Moffat was nomadic early on, he and his wife, Mary, eventually settled at Kuruman, Africa. In 1840, Moffat published a translation of the New Testament in Tswana and the whole Bible in 1857. Outside of his translation work, Moffat’s most significant work was a book simply entitled Missionary Labours; it is to this book we now turn.[5]

Moffat published this book during a furlough back to England in 1840. It made him one of the most well-known missionaries in all of Britain, though – as already noted – his son-in-law would later surpass him in notoriety. Moffat proved himself to be a pioneer of the gospel-centered movement, for he was gospel-centered before it was even a “thing.” In this book, one can undeniably see the gospel-centeredness of Moffat’s mission in four distinct ways.

1. Moffat’s resolve to make gospel preaching his primary work.

Robert Moffat believed that preaching the gospel was the main work of a missionary. In essence, it’s what makes a missionary, a missionary. The preaching of the gospel could lead to the embrace of the gospel, which would result in the salvation of lost souls. Moffat wrote, “[The missionary] knows full well that, if he wishes to save souls, he must preach Christ, the power of God and the wisdom of God, without which all of his efforts to save souls must be like the sounding brass and tinkling cymbal” (79).[6] Moffat noted that it was the “simple gospel” that was able to “[melt]… flinty hearts” (129). Therefore, he “embraced every opportunity of telling [Africans] the simple truths of the gospel, and labored to impress on their minds the blessings of peace” (133). When not able to preach the gospel, Moffat was most grieved, for he wanted Africans to know “about [Christ] who came to redeem the poor and needy” (42). If Africa was to “survive [kinds of] devastations,” then it was going to be by the “diffusion of the gospel” (160). In like fashion, missionaries should depend on the gospel as the means God has determined for the salvation of all who believe (Romans 1:16).

2. Moffat’s belief that no change could take place apart from the gospel’s power.

Moffat believed that no true civilization of the African people could take place apart from an embrace of the gospel.[7] He believed that gospel belief would lead to gospel change, thus civilizing, to some extent, the people of Africa. Moffat noted the changes in one formerly, war-hungry man, Africaner. Though he used to go about the land waging war with various tribes, Africaner came to believe in the gospel and became a vital partner of Moffat’s. He “so fully [came to] understand and appreciate the principles of the gospel of peace, that nothing could grieve him more than to hear of individuals or villages contending with one another” (30). The man who once consistently shed blood eventually “proposed to return [home] rather than run the risk of shedding blood” (34). Before his death, Africaner said, “We are not what we were, savages, but men professing to be taught according to the gospel. Let us then do accordingly. Live peaceably with all men, if possible” (49). Many wanted to civilize the Africans, and Moffat would have agreed with this. But, he understood his mission to primarily be evangelization, for by it, the by-product of civilization could come. He wrote:

[It] was no more in our power to change their hearts, and we were convinced that evangelization must precede civilization… The gospel teaches that all things should be done decently and in order; and the gospel alone can lead the savage to appreciate the arts of civilized life as well as the blessings of redemption (130, emphasis mine).

Likewise, there are many beneficial by-products to one’s mission work today, but above all else, the missionary’s resolve should be to preach the simple gospel. There are many beneficial by-products to one’s mission work today, but above all else, the missionary’s resolve should be to preach the simple gospel. Click To Tweet

3. Moffat’s understanding of African wickedness, which could only be remedied by the gospel.

Moffat understood and saw the wickedness of these people, and thus, their dire need for the gospel in order to be changed. Moffat saw Africa as “a land of darkness and the shadow of death,” for it was “spiritually buried, and without knowledge, life, or light” (69). In Africa, one could see the “dreadful effects of sin” (97). To add to the list already given, Moffat wrote:

[Idols] and idol temples are resorted to by millions of devotees; [the African’s] ears are never stunned by their orgies; his eyes are not offended by human and other sacrifices, nor is he the spectator of the unhappy widow immolated on the funeral pile of her husband; the infant screams of Moloch’s victims to propitiate the anger of imaginary deities (64).

While the greatest benefit of the gospel is eternal salvation, an added benefit is that it makes this temporary life much more joyous. Not only could the gospel lead men to an eternal heaven, but Moffat also believed it could lead them out of an earthly kind of hell.

4. Moffat’s perseverance to preach the gospel in the midst of fruitless labor.

Moffat was perseverant to proclaim the gospel even in the midst of fruitless labor. For ten years, Moffat worked in Africa “without any fruit” (124). However, he and others “continued [their] labours… fruitless as the past had been” (125). He says of their work: “We preach, we converse, we catechise [sic], we pray, but without the least apparent success.” (75) Therefore, he believed the “missionary requires incessant patience and perseverance” (78). Once he finally had a convert, he writes of his immediate surprise: “We had so long been accustomed to indifference, that we felt unprepared to look on a scene which perfectly overwhelmed our minds” (129). Surely, this moment and others like it were worth the years of fruitless labor. Furthermore, Moffat had an understanding of God’s sovereignty that allowed him to relax and trust God with the planting of the gospel seed, for he knew God would cause whatever growth He wanted. Moffat’s faith was “in the unchangeable purposes of Jehovah” (76). God knew what He was doing with their labor, both fruitless and fruitful.

Robert Moffat should not be removed to the missiological dustbin. Rather, he is a man to be remembered and admired for his full adherence to the gospel, shown in these four ways. Missionaries, today, should emulate his understanding of the Christian mission. My encouragement is to read of Moffat’s adventurous life in Missionary Labours and Scenes in South Africa. In it, you will discover that while much good can be done, no good can be done like that of preaching the gospel for both earthly and eternal change in those who do not know the Lord.

Endnotes

[1] For more on the holist-prioritist-liberationist debate, see David Hesselgrave, “Holism and Prioritism: For Whom is the Gospel Good News?” in Paradigms in Conflict: Ten Key Questions in Christian Missions Today, 117-139 (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2010). A new edition of this book will be released next month and is now available for pre-order. See also Jason Sexton, ed., Four Views on the Church’s Mission, Counterpoints (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2017).

[2] Jay Milbrandt, The Daring Heart of David Livingstone: Exile, African Slavery, and the Publicity Stunt that Saved Millions (Nashville, TN: Nelson Books, 2014), 226.

[4] Ruth Tucker, From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya, Second Edition (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2004), 149.

[5] For this biographical information and more on Robert Moffat, see Andrew C. Ross, “Moffat, Robert,” in Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, ed. Gerald Anderson, 464-465 (New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 1998) and the aforementioned chapter from Ruth Tucker’s book, From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya, 148-155.

[6] The citations from Missionary Labours noted in this article come from the following edition of the book: Robert Moffat, Missionary Labours and Scenes in Southern Africa (London: John Snow, Paternoster Row, 1846).

[7] By “civilization,” I do not mean the colonization or the westernization of the people of Africa in regards to their ways, customs, and culture. Rather, Moffat understood that only the gospel could morally changea culture knee-deep in sinful practices.