Hudson Taylor: The Poverty Gospel and Divine Providence

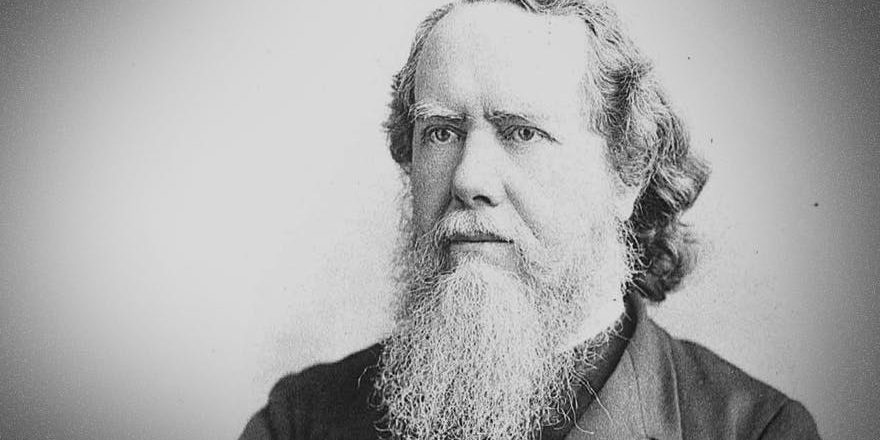

Hudson Taylor (1832-1905) is easily one of the most notorious missionaries of the modern missions era. His missionary call led him away from the medical field of England to the unengaged plains of China, where he first served with the Chinese Evangelization Society (CES). After a few years, Taylor had a short furlough in England and—partially due to missiological differences with the CES—went back to China in 1865 to officially established the China Inland Mission (CIM) with twenty-four other workers. The CIM’s main purpose was—and still is—to go into the pioneer parts of China to preach Christ to the “overwhelming multitude,” that was “altogether beyond the sound of the gospel.”[1] The CIM is still in existence today, though it is now known as the Overseas Missionary Fellowship International.[2] For his work on the mission field, especially with the latter agency he founded, Taylor—again—is venerated as one of the greatest missionaries of the past two millennia. Not only did he give most of his life to reaching lost souls with the gospel, but he also called for more of England’s believers to give their own lives to those same lost souls, especially in his convicting and convincing work, China’s Spiritual Need and Claims.[3]

A Prominent Theological Motif in Taylor’s Autobiography

In a fashion similar to the great George Muller, Taylor—throughout his life—showed a consistent dependence on God.[4] Yet, he differs from Muller in that he ministered in a hostile country. Taylor’s life of dependence is especially noted in his autobiography, originally published under the title, To China With Love. As one might expect, there is not much of an overarching purpose in his Autobiography.[5] For the most part, Taylor simply recounts his early life, his call to ministry, and his work in China, which eventually led to the establishment of the CIM. However, one theme of his life and work is more apparent than others: Hudson Taylor radically depended on God for the duration of his ministry, both in and outside of China. He was a staunch defender of God’s providence.

From an early age, Taylor was prone to depend on God in an extreme way, to say the least. Primary evidence for this lies in his prayer life. Taylor wrote, “[From] the beginning of my Christian life I was led to feel that the promises [of God] were very real, and that prayer was a sober matter-of-fact transacting business with God, whether on one’s own behalf or on behalf of those for whom one sought His blessing” (13). He believed God in this way because he saw the sincere prayer lives of his mother and father; his mother prayed for his salvation, while his father prayed that their son might give himself to China. Both of their yearnings to God were answered, and Taylor truly believed that both took place because his parents diligently sought the Lord. Later in life, in the midst of many difficult circumstances in England, Taylor often described his days this way: “I gave nearly the whole Thursday and Friday—all the time not occupied in my necessary employment—to the earnest wrestling with God in prayer” (29). When Taylor arrived in China, he was resolved to do much of the same. He wrote, “God encouraged me, ere landing on China’s shores, to bring every variety of need to Him in prayer, and to expect that He would honor the name of the Lord Jesus, and given help which each emergency required” (58). Undoubtedly, Taylor was a man of prayer.

This utter dependence on God—primarily exhibited in prayer—directly impacted Taylor’s beliefs and practices concerning evangelism and God’s sovereignty over salvation. Taylor was diligent to evangelize everywhere he went in China but knew that he needed “the power from on high to convince and convert” (78). Taylor writes, “[No] conversion ever takes place save by the almighty power of the Holy Ghost” (47). This belief helped Taylor in the midst of fruitless labor and other, common missionary difficulties. Others looked at Taylor’s life and were astonished to see God’s “remarkable provision” over him (137). The unknown editor of his Autobiography summarizes Taylor’s life well: “Few missionaries have seen their prayers so vividly answered and their heart’s desires so largely fulfilled” (155). Taylor is an example that the Lord provides for his people, and so, God’s people should depend on Him for all things.

What’s more, while Taylor’s prayer life was admirable and his theology of evangelism exemplary, it is not the only evidence of his dependence on God. He sought to prove his dependence on God in other ways. This leads us to examine a motif most prominent in Taylor’s theology of providence: a kind of poverty gospel. He thought the blessings and promises of God would only come to pass if he gave himself, intentionally, to a life of little—indeed, almost nothing; moreover, he thought he could only become fit for mission in China if he gave himself to this. In preparation to live in China, Taylor decided to rid himself of life’s comforts, “in order to prepare [himself] for rougher lines of life” (17). So, he eventually left “the comfortable quarters and happy circle in which [he] was… residing” (18). Taylor came to find that he could “live upon very much less than [he had] previously thought possible” (21). Instead of depending on the means of God, Taylor concluded that he must depend on God, himself. It was the “living God alone” that Taylor would “depend upon… for protection, supplies, and help of every kind” (21). Yet, there was a misstep. While Taylor trusted in God’s providence, he often neglected to accept the means God intends to use to provide for His people. Click To Tweet

At times, Taylor took his dependence on God too far (if one even considers that a possibility). While Taylor trusted in God’s providence, he often neglected to accept the means God intends to use to provide for His people. While in England, Taylor’s boss once told him to regularly remind him of his payday, but Taylor decided he would never do so. He wanted God to remind his boss instead. At one point, because of this, Taylor writes, “I found myself possessed of only a single coin—one half-crown piece” (22). In the midst of this, Taylor owed his landlord rent, but he did not (and could not) pay it because he would not remind his boss of the money due him. In some sense, Taylor was proving himself, to himself. He once asked, “Can I go to China? Or will my want of faith and power with God prove to be so serious an obstacle as to preclude my entering upon this much-prized service” (28)? On one occasion, Taylor thought of going back on his decision to not remind his boss, but he didn’t, for “to do so would be, to myself at any rate, the admission that I was not fitted to undertake a missionary enterprise” (29, emphasis mine). Before he set sail for China, two separate individuals offered Taylor funds for his trip, but he rejected their money and said he was “simply in the hand of God” (33). To prove himself even more, Taylor later decided to live “almost exclusively on brown bread and water” alone, which almost led to his death in a time of sheer sickness (34). Taylor’s beliefs and actions concerning God’s providence leads us to a simple question:

Can God not bless His people through means, particularly by using His own people?

The answer is yes: He can and He does.

Taylor’s Move to a More Biblical Theology of Providence

Thankfully, he wasn’t done formulating his theology, which would go on to impact his missiological practices. Taylor changed his mind. On the way to China, he refused to wear a swimming belt.[6] He felt that in “[his] own soul… [he] could not simply trust in God while [he] had this swimming belt; and [his] heart had no rest until on that night, after all hope of being saved was gone, [he] had given it away” (55). However, he later corrected himself. He made a turn to believing that God does use means to help His people, and those means often come through His people blessing one another in particular ways. Taylor concluded, “The use of means ought not to lessen our faith in God; and our faith in God ought not to hinder our using whatever means He has given us for the accomplishment of His own purposes” (55). He continued, “[To] me it would appear as presumptuous and wrong to neglect the use of those measures which [God] Himself has put within our reach, as to neglect to take daily food, and suppose that life and health might be maintained by prayer alone” (56).

The implications of believing Taylor’s earlier “poverty gospel” are many and dangerous. As noted, Taylor often lived unnecessarily under his means, refused needed medical treatment, neglected to pay those he owed money, risked his life on at least two separate occasions, denied others the blessing that is being a blessing, and failed to acknowledge God’s power to use human means in order to accomplish His divine end. Theologians and missionaries alike—or may I say missiological theologians and theological missionaries—must take this to heart. Paul, as an ultimate example for us, trusted in God’s providence in both good and bad circumstances, for his contentment was in a God who would never forsake him, whether he faced plenty or little (Phil 4:10-13). Though we should not desire to the riches of this world, it is fine and well to desire the basic necessities of life: “food and clothing” (1 Tim 6:8-9). Our call is to be faithful with what God stewards to us—not to seek poverty in hopes that God might bless us or make us more fit for His work (1 Cor 4:2). And if blessed by God in ways others are not—that is, if we are given prosperity—this is not an evil thing; rather, it is a greater opportunity to “share with anyone in need” (Eph 4:28).

In His providence, God “richly provides us with everything to enjoy” (1 Tim 6:17). We are able to find enjoyment even in the “toils” of this life, for all comes “from the hand of God” (Eccl 2:24). All in all, we should admire Taylor’s dependence on God, mimic his prayer life, and practice his model of evangelism; however, we should also be wary of his earlier beliefs and make sure that in our fleeing a prosperity gospel, we do not find ourselves embracing a poverty gospel.

Endnotes

[1] Hudson Taylor, China’s Spiritual Need and Claims (Seattle, WA: Amazon Digital Services LLC, 2012), Kindle Location 766.

[2] Their ministry is still “to the people of East Asia, expressed through many evangelistic and mobilization strategies… [and] focuses on seeing individual lives and whole communities redeemed by the gospel.” For more, see: https://omf.org/us/about/.

[3] Two helpful biographies on Hudson Taylor can be found at the following websites: https://www.christianitytoday.com/history/people/missionaries/hudson-taylor.html and https://omf.org/us/about/our-story/james-hudson-taylor/.

[4] Taylor and Muller were actually good friends, and Muller heavily supported Taylor’s ministry. Their correspondence is noted in Vance Christie’s book, Hudson Taylor: Gospel Pioneer to China (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2011), 172ff.

[5]Going forward, I will refer to this book as Autobiography. Any citations will come from the following edition: J. Hudson Taylor, Hudson Taylor: The Autobiography of a Man Who Brought the Gospel to China (Minneapolis, MN: Bethany House Publishers, 1987).

[6] By “swimming belt,” Taylor could have meant the device used to help one learn how to swim or the device used to help one float in case he was thrown overboard, much like a life vest.