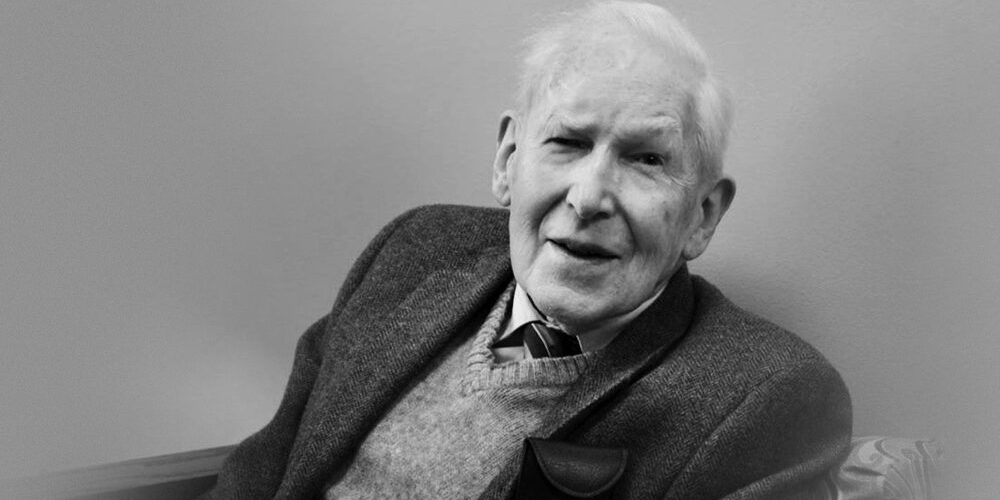

Theology for Worship: A Gift from James Innell Packer (1926-2020)

Theology teaches us how to apply revealed truth for the leading of our lives; thus theology guides our steps, grants us vision, and fuels our worship, while at the same time disinfecting our minds from the inadequate, distorted and corrupt ideas of God and godliness that come naturally to our fallen intellect.[1]

In my first interaction with J.I. Packer he disappointed me greatly, while in the second he granted me an unparalleled gift. Our common story encompasses one international religious movement, two diverse denominations, and three theological institutions. Packer was a committed Anglican and conservative evangelical who entrusted his Oxford institutional legacy to this Southern Baptist for several years at the end of the twentieth century. As a student and pastor, I first gravitated toward Packer’s view of inerrancy. Later, I grew in my appreciation for Packer’s theological legacy, especially his thorough integration of theology with worship. Because worship and theology may not be sundered, he warned against human images made by hand or by mind.

Oxford and Latimer House

The first time we interacted was when I telephoned his home in Vancouver in order to invite him to deliver a lecture series at The Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas. Fulfilling my duty as the student-elected Theological Chairman of the Theological Fellowship, this was my first time to engage a world-renowned theologian. I still remember that personal trepidation in 1990—words could barely be formed. When he was offered our school’s lectureship, with the proposed subject of Biblical Inerrancy, he thought for a moment then turned it down flatly. He was apologetic to me personally but expressed dissatisfaction with comments from a prominent Southern Baptist a few years beforehand. I was devastated.[2]

The second time we interacted was seven years later, when Packer was the most influential member of an Oxford institute’s governing council. That council, to my surprise, first nominated then elected me to receive the important office Packer himself once held. Alister McGrath said Latimer House was “the leading evangelical research think-tank and resource centre for evangelicals within the church of England.”[3] My appointment was a surprise, primarily because I had not sought the office. It was also a great gift, because it gave me unhindered access to numerous rare resources that Packer had gathered and that I needed in order to write my doctoral dissertation at the University of Oxford.[4]

Oxford was important in the religious life of Packer. There are three substantial evangelical Church of England congregations in the ancient city. Packer was converted to Christ in the first, St. Aldates, in 1944.[5] His family worshiped regularly at the second, St. Andrews, as later did mine.[6] It was at the third, St. Ebbes, that the first meeting of the Oxford Evangelical Research Trust was held in 1958. This trust, chaired by John R.W. Stott, purchased a large house at 131 Banbury Road, naming it “Latimer House.” The new Oxford institute was conceived as a sister to Tyndale House in Cambridge, with the former fostering historical and theological studies while the latter fortified biblical studies. The stated purposes of Latimer House were threefold—to support select researchers, to foster collaboration among Anglican scholars, and to “strengthen the evangelical witness in Oxford.”[7] It was during his decade at Latimer House (1961-1970) when Packer began to grow in fame.

So, why did a little-known Baptist succeed J.I. Packer as Librarian of an Oxford institute committed to the study of Anglicanism? Later, I learned the reasons my name was unanimously approved: A close friend, Nigel Atkinson, was the previous Warden; our host, John Reynolds, was one of the council’s founding members; and the most influential member of the council was the theologian who once turned down my heartfelt invitation to speak on a doctrine we together cherished. From an apologetic perspective, since a leading evangelical Anglican, Timothy Bradshaw, was the Vice Principal at the Baptist college affiliated with the University of Oxford, it seemed equitable to invite an evangelical Baptist to lead an Anglican institute. After all, one of Latimer House’s purposes was to “strengthen the evangelical witness in Oxford,” and I was a known evangelical.[8]

Theology and Imagery

Returning to Fort Worth in 2000, Packer as a systematic theologian accompanied me into the classroom, in written rather than personal form. The first text the students read was Knowing God, a million-copy bestseller whose contents were penned during Packer’s tenure at Latimer House. One of the most difficult parts of that volume for the students was chapter four, “The Only True God.” Packer argued stringently against idolatry, including the creation of images. Questions arose due to the presence of two striking life-size statues of Jesus on our seminary’s campus, posing as a fisherman and washing the feet of Peter. “How,” they asked, “can our seminary have images on campus while our professor assigns Packer’s text, which equates images with idolatry?”[9]

Packer identified images as an impediment to worship and thus verboten after the Bishop of Woolwich, John A.T. Robinson, penned a newspaper opinion piece in 1963 entitled, “Our image of God must go.”[10] Soon, Robinson’s controversial book, Honest to God, appeared and sold over 350,000 copies in seven months. Sensing the need for an immediate response, Packer penned at his desk in Latimer House “by far the best evangelical critique of Robinson.”[11] Keep Yourselves From Idols dismantled Robinson’s theology. His tone was justly learned and justly scathing.[12] The problem was not Robinson’s laudable goal to reach modern men and women. Rather, his “teaching makes true worship impossible.” The mental image Robinson created was of a god who is “not a person” and “has done nothing to be praised for.” And the new Jesus Robinson manufactured “was not God in any personal sense.” The only worship we can pursue is, finally, “self-worship.”[13]

Packer’s disdain for icons was thus aroused by the huge threat posed by the “mental image” created by a respected religious authority who forsook his call to preach the Word. In Knowing God, Packer reflects theologically on the second commandment, which states, “You shall not make for yourselves an idol.” He leaves some room for images but not much. The second commandment’s “categorical statement rules out” the “use of pictures and statues” whether of creatures or “of Jesus himself.” Packer admits the prohibition applies primarily to their use “in worship,” but he doubts they can be used “for purposes of teaching and instruction.”[14]

Why does Packer object? “The heart of the objection to pictures and images is that they inevitably conceal most, if not all, of the truth about the personal nature and character of the divine Being whom they represent.” He is not opposed to religious art “from a cultural perspective” but to its inappropriate usage.[15] God is “jealous” for our worship, and imagery “perverts our thoughts of him and plants in our minds errors of all sorts about his character and will.” This problem arises equally with the “molten images” conveyed in pictures or statues and with “mental images” conveyed in speculative theology.[16] Human constructions bypass the way God intends us to perceive Him, which is through God’s inspired Word. Worshipers of golden calves and crucifixes want to “see” God, but God wants us to “hear” Him through Scripture.[17]

Packer’s conviction to help others rightly worship God through biblical proclamation was reinforced by his studies of the Reformers and the Puritans. The Reformers uniformly agreed that Scripture was authoritative. They also taught that salvation came by grace to those who heard the Word of God proclaimed.[18] However, one of the unsolved problems of the Reformation tradition concerned exactly what we may incorporate from beyond Scripture in worship.

In order to preserve the true worship of the true God, should we only worship in ways expressly commanded by Scripture, according to the regulative principle? Or may we incorporate orderly practices not prohibited by Scripture, according to the indifference principle? The answers divided the Puritans. Packer tried to be generous toward those who took either approach.[19] Our answers should not separate evangelicals in different denominations from seeking fellowship with one another.[20] What brings us together is the truth that the Spirit uses the Word of God to regenerate believers so that we worship the triune God.[21]What brings us together is the truth that the Spirit uses the Word of God to regenerate believers so that we worship the triune God. Click To Tweet

In the numerous Puritan Papers he edited at Latimer House, Packer worked closely with scholars like Martyn Lloyd-Jones and Iain Murray on issues of theology and worship.[22] However, the English Evangelical movement soon fractured, because Lloyd-Jones began to promote a pure church ideal with a more regulative principle. In one controversial incident, Lloyd-Jones issued a call which was summarized in the headline, “Evangelicals—Leave Your Denominations.”[23] John Stott, breaching protocol, immediately opposed Lloyd-Jones from the same platform. Packer quietly sided with Stott, believing evangelicals may work together while staying in their denominations, even those wherein there are doctrinal disagreements.

Conclusion

James Packer was perhaps the most sophisticated and most eloquent Anglican theologian of the twentieth century. He simultaneously remained a committed evangelical, a committed Anglican, and a committed ecumenist to the end of his days. His numerous accomplishments are both important and helpful. He was a founding member of the International Council of Biblical Inerrancy, providing the current generation with a sophisticated and defensible doctrine of Scripture against the challenges of liberalism. However, as seen in his famous book, “Fundamentalism” and the Word of God, he would not allow fundamentalism to define evangelicalism either.[24] Packer was also committed to theological excellence, identifying personally with the Reformed tradition, at the same time that he was committed to effective evangelism.[25]

The Latimer House Council’s unexpected gift blessed my scholarship profoundly. The library was large and filled with rare works from the English Reformation. Most of the books—in English, Latin, and German—were brought into the collection during Packer’s tenure. His mark was on nearly every flyleaf I opened. His large desk—our desk—was adorned with a sixteenth-century Geneva Bible, among other priceless and useful treasures. For several years, it was a joy to use Packer’s desk and follow Packer’s lead in reading—nay consuming—the works of Reformers and Puritans. From a scholarly perspective, the young man who had been refused one gift was granted something far greater.[26] From a spiritual perspective, deep exposure to Packer’s Anglicanism led me to appreciate the integration of theology and worship.

The integration of true theology with worship led Packer to hold the line against image-making. That same desire led him to ensure that the drawing of theological lines was both biblical and loving, rather than a matter of interpretative disagreement and censorious spirit. Thank you, J.I. Packer for giving this Baptist the opportunity to serve a significant Anglican institution which you built.[27] Thank you, moreover, for teaching evangelicals that every construction is subject to idolatry if it is not granted by the Spirit through the Word for communion with the triune God.

Footnotes

[1] James I. Packer, “The Preacher as Theologian: Preaching and Systematic Theology,” in Honouring the Written Word of God, The Collected Shorter Writings of J.I. Packer 3 (Carlisle, Cumbria: Paternoster Press, 1999), 306.

[2] After consulting with my theological mentor, James Leo Garrett Jr., I instead invited David S. Dockery, the newly elected Dean of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Dockery delivered the Spring 1991 lecture on “Contemporary Options in Understanding Biblical Inspiration.” A deep friendship developed with that great theologian and current colleague at Southwestern.

[3] Alister McGrath, J.I. Packer: A Biography (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1997), 116.

[4] The Librarian position likely shaved a year off my research. The dissertation, whose central chapters were devoted to Thomas Cranmer’s theology of priesthood and worship, was approved in 2000 by Rowan Williams and Diarmaid MacCulloch and subsequently published as Royal Priesthood in the English Reformation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[5] McGrath, J.I. Packer, 17.

[6] McGrath, J.I. Packer, 135.

[7] McGrath, J.I. Packer, 103-5.

[8] There was another reason, for which my gentle yet forthright personality was ideally suited, but I shall leave that matter for the former members of the council to divulge at their discretion.

[9] I once led two seminary presidents past the Jesus statues and stooped to point them out. R. Albert Mohler Jr. raised his eyebrows; the other vowed to place what donors funded.

[10] Alister McGrath, The J.I. Packer Collection (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1999), 57.

[11] McGrath, The Packer Collection, 57.

[12] “Indeed, for one of such an original mind as Dr Robinson, its ideas are surprisingly secondhand; it is just a plateful of mashed-up Tillich fried in Bultmann and garnished with Bonhoeffer. It bears the marks of unfinished thinking page after page.” The Packer Collection, 61. His conclusion from a scholastic perspective was that Robinson made “sweeping generalizations” suggesting a “superficiality of study.” Honest to God “betokens more of sentiment than of thought.” The Packer Collection, 71.

[13] The Packer Collection, 66.

[14] J.I. Packer, Knowing God: 20th-Anniversary Edition (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993), 45.

[15] Packer, Knowing God, 46.

[16] Packer, Knowing God, 47-48.

[17] Packer, Knowing God, 49. The image which God creates for us through Scripture is of Jesus Christ at Calvary. Those were Packer’s thoughts in 1963. In 1993, he answered three objections to his earlier diatribe against images with three subtle answers. Packer, Knowing God, 50-51.

[18] Packer, “The Puritan Approach to Worship,” in Puritan Papers: Volume Three, 1963-1964, ed. J.I. Packer (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2001), 5.

[19] Packer, “The Puritan Approach to Worship,” 7-11.

[20] Packer deemed the regulative principle a “Puritan innovation.” Packer, “The Puritan Approach to Worship,” 6.

[21] Packer, “The Puritan Approach to Worship,” 12, 18.

[22] Iain Murray, “Scripture and ‘Things Indifferent,’” in Puritan Papers: Volume Three, 21-50; Martyn Lloyd-Jones, “John Owen on Schism,” in Puritan Papers: Volume Three, 83-116.

[23] McGrath, J.I. Packer, 125.

[24] J.I. Packer, “Fundamentalism” and the Word: Some Evangelical Principles (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1958), 21-40.

[25] J.I. Packer, Evangelism and the Sovereignty of God (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1961).

[26] There were light administrative duties affiliated with the office, but they were certainly not burdensome. Indeed, I tried to refuse the salary they offered, for I felt as if they had given me something that sped my research.

[27] Perhaps because of our common theological commitments, the Latimer House theologians, alongside two bishops, long tried to convert me to Anglicanism. For all my appreciation of Packer as a theologian, infant baptism and episcopacy remain significant problems.