Retrieving an Ancient Sacramental Ecology: Series Recap

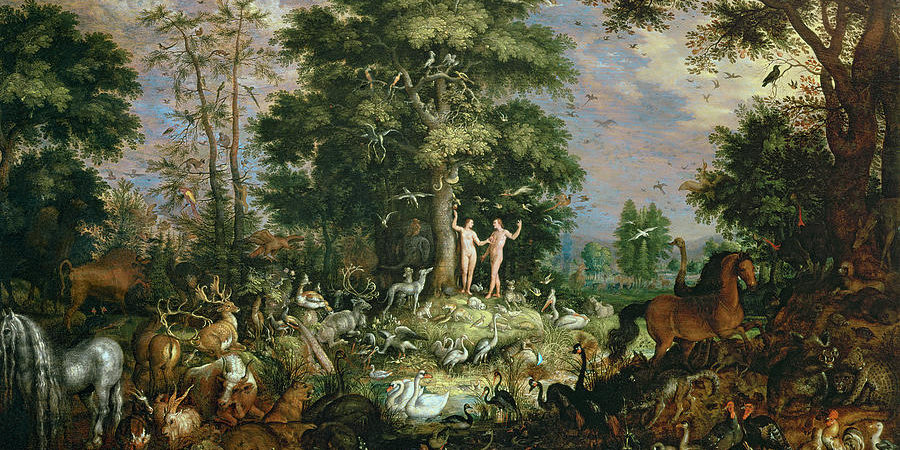

Recently, Credo featured a blog series written by James C. Ungureanu about the need to recover an ancient sacramental ecology. In these essays, Ungureanu recounts the history of sacred ecology, from the enchanted view of the ancients to the naturalistic and frankly unenchanted conception of nature that arose in the post-Enlightenment world. As he traces this history, he offers a corrective to some common misconceptions that many Christians hold concerning the role of the natural world, and thus their care for it. Additionally, Ungureanu points readers to Scripture and to the voices of Lewis, Tolkien, and Shaefer as he seeks to cultivate in them a truly Christian, sacramental ecology.

Retrieving an Ancient Sacramental Ecology, Part 1

Humanity, therefore, is commissioned to rule nature as a benevolent king. And in this sense, humanity’s dominion should resemble God’s dominion. The Byzantine monk John of Damascus (675-749), for example, says that God furnishes man with counsel, glory, eyes, conscience, and knowledge in order to exercise his rule properly. The Cappadocian bishop Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335-395) similarly argued that God has appointed us as “lords” (kurios) over the earth, to fill the earth with “reason” (logos). For St. Augustine, humanity should not be an “exploiter” of God’s gifts of nature, but rather an “explorer” who conforms to God’s will. Indeed, St. Augustine vigorously affirmed the inherent goodness of the world against the Manichean attempt to denigrate it, and frequently invoked the beauty of nature as evidence for its God’s goodness. Man, therefore, must rule over creation as God rules over man. As master of creation, God calls man to be a good ruler, not by exploiting nature for his own purposes, but caring for it. Thus while the early church fathers did say that earth has been made for the benefit of man, they never suggested that the earth should be exploited for our benefit.

Part 2: The Cultural Mandate

The early church did, to be sure, enjoin its followers to beware of entanglement with the “world,” but world here means not the visible world, the created order, the cosmos in our current sense, but rather its opposite: “worldliness” as in society and its preoccupations, the artificial network of vanities and ambitions that humans have everywhere fabricated—the world of human contrivance rather than that of divine creation. In short, authentic Christian faith includes care for the earth and its many creatures. Such stewardship of nature is integral to Christian discipleship. It is embedded in what we sing (doxology) and pray (Lord’s prayer) and confess (Apostles Creed). Such a theology is biblical and sacramental, from the very first to the last chapters, for Scripture begins and ends with rivers and trees, and a God who creates and sustains and will bring to perfection all things with heaven on earth.

Part 3: “On the Dignity of Man” and the New World

It seems that far from the Christian tradition being seriously culpable in the generation of environmental crisis, our current ecological problems stem from ideas founded among more worldly thinkers with more worldly goals. Although the advent of modern science and industrialization have contributed to human flourishing, the ecological problems arising from this activity cannot be overlooked. Those engaged in scientific pursuits must therefore exercise caution. In the pre-modern Christian view, humanity was given dominion over creation as a divine representative. This injunction, bound up with our being made in God’s image, indicates that dominion is an essential part of our human identity. Thus our destiny and the destiny of the Creation are intertwined.

Part 4: The Inklings

Both Tolkien and Lewis thus believed that the cosmos in general and the earth, in particular, were created by a good, caring, and loving Creator and were themselves proclaimed by that Creator to be good. The call to care for that good Creation is central to the created purpose of humans. Having personally witnessed the awful prodigy of modern industry and technology, Tolkien and Lewis enlisted Creation itself as a protagonist in their epic stories of good versus evil. Like many in the early church, they understood the Imago Dei not as imparting to us the right to exploit but rather the responsibility to serve. As bearers of God’s image, they believed Christians had a profound ecological responsibility. In the Christian imagination of Lewis and Tolkien, the assault upon nature carried spiritual significance.

Part 5: How Should We Then Live?

Schaefer, Tolkien, and Lewis all advocated a “spiritual transformation,” a return to an ancient sacramental ecology, as the only way forward. The accusation that Christian theology has led to our current ecological crisis is based on selective readings. For the Christian, there is an obligation to care for nature. Indeed, environmental stewardship is not crisis management but a way of life. God’s call to serve and keep the garden is our calling whether it is our vegetable garden or the whole of creation. We need not have all the data, but we must be dedicated to imitating God’s love for the world in our lives and landscapes.

The human calling to have “dominion over the earth” is that of a royal priest, not a sovereign despot. God did not place everything under humanity’s feet to be trampled on. Rather, the purpose is to further God’s glory by intelligent, respectful, obedient governance that reflects God’s own love and care for the earth. God created the world, holds everything together, and reconciles all things through Christ. Since the days of the early church, followers of Jesus have known this remarkable teaching. Since “the earth is the Lord’s,” humanity’s responsibility to “serve and keep” Creation has been part of the belief and practices of God’s people for millennia. As Christians, we must recognize that our environmental problems are more spiritual than technological. People everywhere are looking for the way, the truth, and the life. The time is ripe for retrieving the ancient sacramental ecology of the early church.