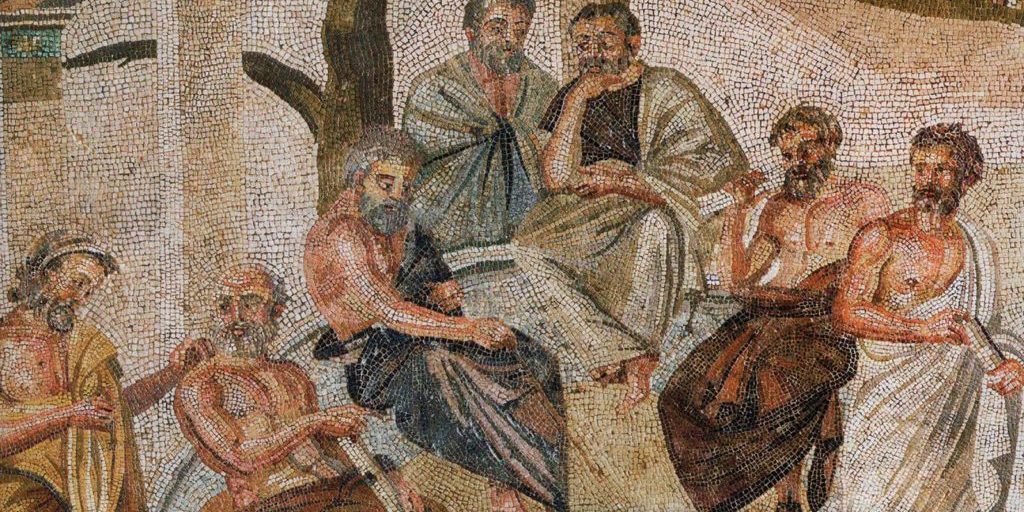

What does Jerusalem have to do with Athens? This was the famous statement made by Tertullian when he challenged the supposed connections between theology and philosophy, the naturally obtained wisdom of humans. From one vantage point, Tertullian echoes the teaching of Scripture. Recall the words of the Apostle Paul: “The natural person does not accept the things of the Spirit of God, for they are folly to him, and he is not able to understand them because they are spiritually discerned” (1 Cor. 2:14). Philosophical knowledge can never serve as a ladder to heaven. For all of their learning, philosophers have never been able to glean the message of the gospel through the power of their own thought or from reflecting on the creation. The saving knowledge of Christ and his gospel is solely the provenance of special revelation and the sovereign regenerative work of the Holy Spirit. To the natural person, the gospel is a stumbling block and folly (1 Cor. 1:23).

The Queen and the Handmaid

But does the antithesis between earthly philosophy and the heavenly knowledge of salvation completely define the relationship between the two disciplines? Is there no function whatsoever for philosophy in theology? While some may latch on to Tertullian’s statement and try to excise all philosophy from theology, historically, the church has admitted a carefully defined role for philosophy in relation to theology. Protestant theologians have acknowledged that theology is the queen of the sciences. That is, theology has a regulative function among the various disciplines of knowledge because of its supernatural source. This is not to say that theology speaks exhaustively to every single conceivable discipline but that it nevertheless serves as a referee to ensure that other disciplines do not cross divinely given moral and ethical boundaries. The Westminster Confession (1647) captures the magisterial role of theology when it states: “The supreme judge by which all controversies of religion are to be determined . . . can be no other but the Holy Spirit speaking in Scripture” (I.x). Good theology has its roots in the rich soil of Scripture and thus serves as the queen of the sciences. But theology’s magisterial role does not therefore preclude the responsible use of philosophy. Protestant theologians recognize that theology is queen of the disciplines and that philosophy is a handmaiden, an ancillary tool that the church may use in the task of doing theology. Or in other words, there is a role for a scripturally subordinated use of natural revelation in concert with special revelation. In the words of the Belgic Confession (art. II), we can use God’s two books, the books of Scripture and nature as we formulate our biblical doctrines.

How have theologians used philosophy in theology? Two examples illustrate the role of philosophy in theology. Despite the fact that Tertullian wanted to distance Jerusalem from Athens, he nevertheless employed philosophical categories such as substance to distinguish the three persons of the godhead from their commonly shared essence. There were some early church theologians who objected to the use of philosophical terms in doctrine because they believed that theology only needed to employ scriptural language to defend and explain the doctrine of the trinity. The problem was, however, that everyone, orthodox and heretic alike, employed scriptural language but did so with different meanings and to disparate ends. Some maintained that the Son of God is only of like substance with God the Father (hence he is only homoiousias), whereas others rightly argued that the Son is of the same substance with the Father (therefore he is homoousias). The terms ousias (essence or substance) does not appear in Scripture, but orthodox theologians debated and used this philosophical term to protect the scriptural teaching that the Son of God is fully divine and equally God. The church’s mature thought on the matter now appears in confessions of faith: “In the unity of the Godhead there be three persons, of one substance, power, and eternity: God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost: the Father is of none, neither begotten, nor proceeding; the Son is eternally begotten of the Father; the Holy Ghost eternally proceeding from the Father and the Son” (WCF II.iii). In the godhead there are three distinct persons that share one substance. The church employs philosophical terms to delineate the boundary between orthodoxy and heresy.

A second example of philosophy in theology comes with the Aristotelian categories of primary and secondary causality to distinguish between divine and human agency: “Although, in relation to the foreknowledge and decree of God, the first Cause, all things come to pass immutably, and infallibly; yet, by the same providence, he ordereth them to fall out, according to the nature of second causes, either necessarily, freely, or contingently” (WCF V.i, emphasis added). This philosophical distinction is vital to demonstrating that God can foreordain and decree whatsoever comes to pass but in no way does violence to the will of creatures or is the author of sin (WCF III.i).

Proper Function

Philosophy can be a useful heuristic device for theologians. But the church must be vigilant lest her theology devolve into philosophy, or that God’s supernatural revelation morphs into merely natural knowledge. As Paul writes: “See to it that no one takes you captive by philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the world, and not according to Christ” (Col. 2:8). A well-known instance of the devolution of theology to philosophy is medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas’s erroneous doctrine of transubstantiation—the mistaken view that the bread and wine of the Lord’s Supper physically transform into the actual body and blood of Christ. Aquinas used Aristotelian categories of substance and accidents to prop up his doctrine in contradiction to the clear teaching of Scripture. In this case, the handmaid usurped the queen’s throne. But here we must remember that the abuse of philosophy should not disqualify its proper use.

The apostle Paul warns against allowing philosophy to take Christians captive but at the same time he quoted pagan philosophy when he presented the gospel to the philosophers at Mars Hill: “For as I passed along and observed the objects of your worship, I found also an altar with this inscription: ‘To the unknown god.’ What therefore you worship as unknown, this I proclaim to you. . . . ‘In him we live and move and have our being’; as even some of your own poets have said, ‘For we are indeed his offspring’” (Acts 17:23-28). Paul refers to Cretica by Epimenides when he says, “In him we live and move and have our being,” and he quotes Aratus when he told his audience that “For we are indeed his offspring.” Paul never allowed these philosophical sentiments to overtake his theological claims, but he nevertheless employed them in subordination to his theological goal of presenting the gospel of Christ. Rather than begin with the Scriptures, as he often did in Jewish synagogues because of their knowledge and familiarity with the Old Testament (Acts 17:2), Paul instead began with philosophical claims familiar to his pagan audience.

For those who believe that we should excise all philosophy from theology do not realize that all of us use philosophical concepts and terms whether we realize it or not. He who believes he is free from philosophy is the likely unwitting adherent to the philosophical teaching of a defunct philosopher or theologian. Rather than run from natural knowledge, or philosophy, we should seek God’s wisdom wherever we find it. Subject to the magisterial authority of Scripture, true philosophy never conflicts with sacred theology.