Faithful Orthodoxy Requires Reading Widely

Recently, one of my students asked me how long I’ve been teaching theology. “Ten years,” I said. And as I walked back to my office and sat down at my desk, a question hovered in my head: What have I left my students with after a decade?

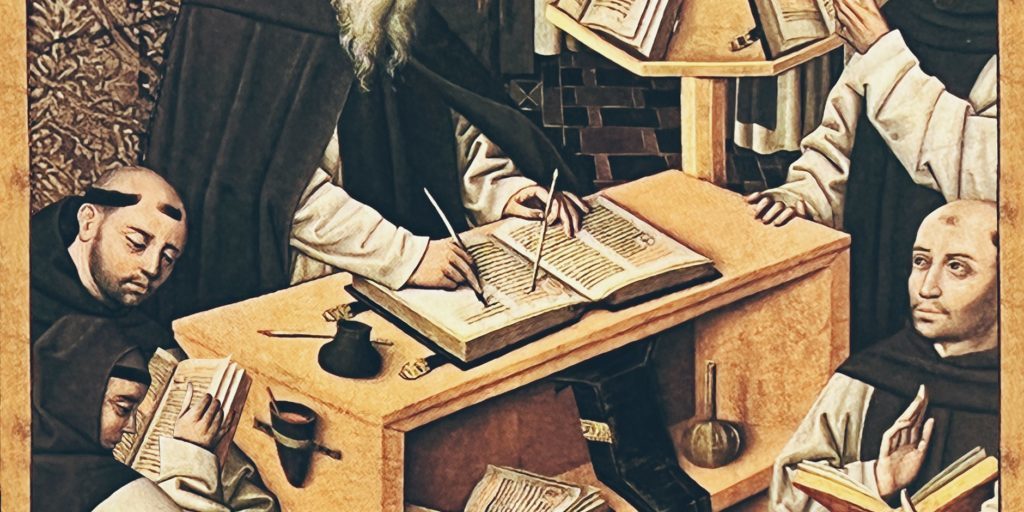

In my self-centeredness, I had assumed I was the one bestowing the gift of knowledge to my students. But in truth, one of the best things I have done is send my students into modern ministry’s stormy seas with time-tested wisdom from an experienced crew from church history.

The longer I teach, the more I resonate with C. S. Lewis’s admonition, “The task of the modern educator is not to cut down jungles but to irrigate deserts.” And yet there remains notable deserts in the world of seminary education, particularly when it comes to incorporating large swaths of Christianity’s Great Tradition.

Years ago, as a PhD theology student at a Protestant seminary, I was handed a list of required reading. Out of 128 books, only three of them (!) were by premodern authors (written from the first century to the 15th century).

Even when I crossed into history with my degree, seminars skipped from the church fathers to the Reformers, only to progress into American history. And since half—yes, half—of church history lies in the Middle Ages, this gap in my education felt like a Grand Canyon. So, I petitioned the school to invent my own independent study of medieval theology and history.

Has anything changed today?

Christopher Cleveland chronicles how evangelical seminaries sought to replace liberal with conservative theologians, and in the process—due to either neglect or avoidance—“a generation of evangelical scholars arose who had no serious acquaintance with the classical categories of theology developed in Patristic, Medieval, and Reformed orthodox thought.”

As Protestants, many of us were taught that everything started off grand in the early church but then the church entered the “Dark” Ages. Thankfully, the Reformers turned the lights back on and established the true church that had been lost since the days of the apostles.

We mistakenly believe the Reformers pursued a total, radical break with the past—a rebellion that started a new church—rather than seeking to renew the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church.Most Protestants today have no idea what occurred in the church for nearly a thousand years. Click To Tweet

The practical implications of this mindset are serious: Most Protestants today have no idea what occurred in the church for nearly a thousand years. Yet they are confident of one thing: Whatever did occur during the premodern era is not worth our time and can only corrupt Christianity.

This is the mindset of many everyday churchgoers, which ultimately trickles down from the preaching in the pulpit. And since most pastors are trained in seminaries, the source of the problem is often in the outlook of Protestant academic institutions.

Those outside the evangelical vortex looking in often ask how this could happen. Many of them attended secular institutions where such a chasm is unthinkable. I wish I could say the oversight is merely administrative, but it is not. Ideas, after all, have consequences.

So, how do we change course? The answer has everything to do with humility.

We all know C. S. Lewis from his famous book Mere Christianity, which emphasized his staunch commitment to orthodoxy—that is, classical Christianity—as non-negotiable.

Yet many forget that in the middle of this classic apologetic, Lewis spends two whole chapters retrieving the intricacies of the Nicene Creed and its doctrine of eternal generation. He also wrote a preface to one of the great works of Christian history, On the Incarnation by the eastern church father Athanasius.

Lewis advised—no, pleaded—with moderns in his generation to read more old books. He did so not because these premodern authors were without foibles. Every generation has its blind spots. But their blind spots are not always our blind spots.Under the threat of modernism’s disenchanted cosmos, Lewis had no patience for the chronological snobbery of his day. Click To Tweet

“None of us can fully escape this blindness, but we shall certainly increase it, and weaken our guard against it, if we read only modern books,” said Lewis. “The only palliative is to keep the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds, and this can be done only by reading old books.”

For instance, Lewis often ruminated on the God-centered vision of medieval theology, which he considered an antidote to the disenchanted cosmos of skeptical modernism so prevalent in his day. As Jason Baxter points out in his recent book, Lewis believed it was “his duty to save not this or that ancient author, but the general wisdom of the Long Middle Ages, and then vernacularize it for his world.”

Under the threat of modernism’s disenchanted cosmos, Lewis had no patience for the chronological snobbery of his day. Fearful such a skepticism could undo Christian orthodoxy itself, Lewis considered such pretentiousness not only ignorant but ungodly.

And so should we. …