The Reformation and Participation

Editor’s note: Matthew Barrett is writing a Systematic Theology and is providing monthly updates on his adventures in research. You can read each update by subscribing to Anselm House.

This past month has been a fruitful month for writing my Systematic Theology (Baker Academic). I have started writing the first chapter which I have tentatively titled “Theology for Seeing God: Theological Theology.” I have especially benefitted from Franciscus Junius’s A Treatise on True Theology, which outlines 39 theses on theological method. Did you know that the Junius Institute has made this treatise available online with the corresponding text in Latin?

Junius offers so much by way of these theses. For example, he did not hesitate to utilize Aristotle’s four causes and even elaborates on a fifth cause to describe theology. I have given some of these causes my own wording for pedagogical use:

Formal cause of theology Divine Truth

Material cause of theology Divine Matters

Efficient cause of theology Divinity (Holy Trinity)

Instrumental cause of theology Divine Discourse

Final cause of theology Divine glory and good of elect

I am adapting Junius and his chain of causation to answer that most important question, What is the goal of theology? By bringing into focus the secondary component of that goal (the good/salvation of the elect) I am giving an answer most unmodern: contemplating God in the beatific vision. (By the way, the next issue of Credo Magazine will be devoted to the Beatific Vision!)

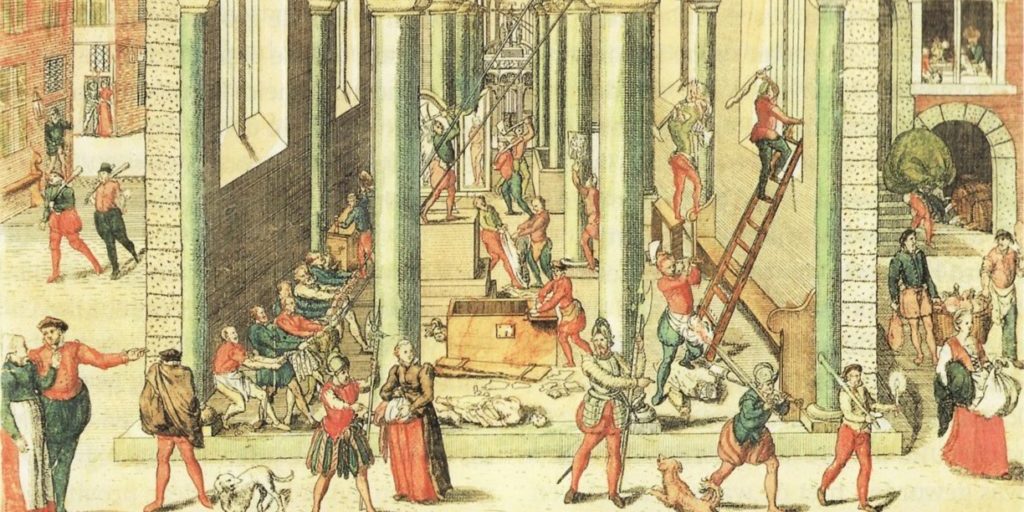

Not unrelated, I have received back from Zondervan Academic my manuscript: The Reformation as Renewal: Retrieving the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church. When I originally started on this voyage, I had no idea my research would pay such dividends for a systematic theology. I could mention many benefits, but one that has and will come across in the first chapter of my systematic is the concept of participation. In The Reformation as Renewal, I give a brief tour beginning with Platonic participation only to move into the ways the East (Athanasius, Cappadocians) and West (Augustine, Aquinas) critically appropriate participation. Everything changes, however, with the rise of Nominalism in the late medieval period (e.g, Ockham, Biel) which I argue possesses the seeds that eventually sever the sacramental tapestry of classical realism (to borrow Boersma’s language). However, I buck against the trend today to blame the Reformers as if they were main carriers of the nominalist disease, like a bridge into modernity and a gateway into secularism. I make a point to highlight how reformers like Calvin did possess a participation theology (much thanks to Todd Billings here), nor can we forget that many of the Reformed Scholastics in the centuries to come chose to align themselves with the realism of via Antiqua rather than the nominalism of the via Moderna.

Speaking of participation, I cannot say enough to praise Jason Baxter’s new book, The Medieval Mind of C. S. Lewis. I had the opportunity to sit down with Baxter on the Credo Podcast—in my opinion, truly one of the best conversations of the year (although, the next episode on partitive exegesis was also a long overdue thrill). The conversation with Baxter explains why we love C.S. Lewis so much—he was resurrecting the participation metaphysic of medieval theology to give an apologetic against the modern (naturalistic) metaphysic of his day and, as it turns out, our own as well (Lewis was prophetic like that).

Since I last wrote I published an essay for Christianity Today. And the title is long enough to tell you what to expect: “Faithful Orthodoxy Requires Reading Widely: Evangelicals should humbly learn from all Christian tradition—yet many are ignorant or suspicious of pre-Protestant theology.” Here’s how I start,

Recently, one of my students asked me how long I’ve been teaching theology. “Ten years,” I said. And as I walked back to my office and sat down at my desk, a question hovered in my head: What have I left my students with after a decade? In my self-centeredness, I had assumed I was the one bestowing the gift of knowledge to my students. But in truth, one of the best things I have done is send my students into modern ministry’s stormy seas with time-tested wisdom from an experienced crew from church history. The longer I teach, the more I resonate with C. S. Lewis’s admonition, “The task of the modern educator is not to cut down jungles but to irrigate deserts.” And yet there remains notable deserts in the world of seminary education, particularly when it comes to incorporating large swaths of Christianity’s Great Tradition.

The rest of the essay gives an apologetic for retrieval in the spirit of C.S. Lewis, though not to forget G.K. Chesterton who said, “Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about.”

In that essay I also share some great news: Crossway plans to publish a multivolume set called Thomas Aquinas for Protestants—edited by me and my friend Craig Carter, with individual volumes by J.V. Fesko, David Sytsma, and Carl Trueman as well. As I say, “we’re not looking to enshrine Aquinas or any other thinker. Rather, we will listen critically but with humility as Aquinas unveils timeless, transcendental insights that serve to recover the eternal goodness, truth, and beauty of God in our disenchanted world.” We will be following in the footsteps of those Reformed Scholastics before us, from Peter Martyr Vermigli to Francis Turretin to John Owen.

As I think about the ways my Systematic Theology will embody classical theology, the beauty of classical theology has weighed heavy on my mind. In light of our participation in the Creator, classical theology is like a tapestry weaving many threads into one, including

classical theism

classical biblical interpretation

classical philosophy

classical apologetics

classical spirituality

I don’t think I will be able to give a full account of each in my systematic, but I do want to model how classical theology weaves each thread into the fabric of the Christian faith as a whole.

By way of update, some of you know that I not only teach theology at MBTS but I’m a pastor at Emmaus Church in KC. Last Sunday I preached on Acts 17—Paul in Athens on Mars Hill. This sermon gave me the opportunity to weave some of those threads mentioned above. I especially enjoyed the way Paul critically appropriates Greek Philosophy to reveal their participation in the true and living God, the Creator to whom they are accountable, the one in whom we live and move and have our being. At the end I laid out several strategies for our mission as a church on the Mars Hills of our day. Next week I preach in chapel at MBTS, and I will be spending this week in preparation. Question is, what text and doctrine to preach on? I decided on 1 Samuel 15 and that perplexing statement, “God was sorry he had made Saul king.” I took this opportunity to define divine impassibility and explain why impassibility springs from the text and is so essential to the classical doctrine of God and even our confidence in the gospel of Jesus Christ.