Choosing Bavinck

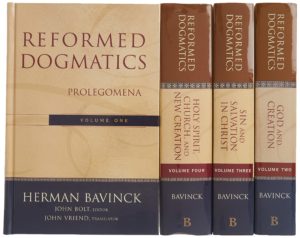

In my first semester teaching at my new academic post, I’ve had the great privilege of teaching Theology 1, which covers an introduction to theology, revelation and Scripture, the existence and attributes of God, and trinitarian theology. Countless evangelical institutions around the world typically work with Wayne Grudem’s seminal work, Systematic Theology. But my first order of business as the Theology Professor here is to make Herman Bavinck’s R eformed Dogmatics our primary textbook.

eformed Dogmatics our primary textbook.

And yes, before anyone asks, a huge reason for this resource-swap comes from my strong disapproval of Grudem’s view of the Trinity, with his Eternal Functional Subordinationism (EFS), but it is so much more than that. My reason for going with Bavinck as opposed to either Grudem or Grudem’s contemporaries (who may or may not espouse EFS) has everything to do with theological method. While my appreciation for, and personal indebtedness to, Grudem runs deep,[1] I simply cannot commend his way of theologizing to my students. What I want to avoid handing down to my students is not just EFS, but more specifically, the theological and hermeneutical habits that produce positions like EFS. But first, a word about some initial considerations for choosing a textbook.

Initial Considerations

I agonized about what to use for a textbook in this class. My difficulty was not owing to indecision about whether to move the typical status quo away from Grudem or not; I knew that I would. Nor was my difficulty owing to the fact that there is a dearth of books to choose from, or because I could not think of anyone who covered the topics I wanted in the manner I wanted (the exact opposite might be the case; if anything, narrowing a massive list of sound theologians down to a reasonable number is always an issue!). Rather, what made the decision difficult had everything to do with the context of my seminary.What kind of Christianity do we want to outsource to the nations? This is the question I perpetually have on my mind. Click To Tweet

You see, ours is the first evangelical seminary to ever exist in the Arabian Peninsula. The Gulf Theological Seminary is located in the heart of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which is one of the most international regions on the planet. Our student body is about as diverse as this region is: we have Indians and Pakistanis and Lebanese and Ethiopians and Kenyans and Colombians and Egyptians and Filipinos and Koreans and more in our student body. Some of our students have been raised in faithful believing households, and some of them are first-generation Christians. Some of our students are here working for wealthy companies with salaries that would make your jaw drop and some live paycheck to paycheck and barely make enough to get by (i.e., their salaries would make your jaw drop for a very different reason). All of our students speak English but almost all of them speak English as a second or third or fourth language. Many of them have been out of school for years, and some of them have never had any schooling in English.

While this rich diversity brings some difficulty for communication, it nevertheless makes the prospect of global church planting very exciting. We have the opportunity to really impact this region (and indeed, the world) with annual crops of graduates who are prepared to take years of ministerial training and apply it to a plethora of contexts. Around here, we like to dream of the UAE being a “Geneva of the Middle East,” from where we can send out pastors to take the flame of reformation-zeal they caught here back to their own (often difficult to reach) homelands, not unlike how Calvin trained up pastors who would turn Europe upside down with the gospel in his own day. So, in a very real way, when I’m thinking about the kind of theology I want to instruct my students with, I am thinking not merely about my present interests, or these individual students, but rather about the churches they will, Lord willing, plant around the globe in due time (as well as the churches those churches will plant, etc.). What kind of Christianity do we want to outsource to the nations? This is the question I perpetually have on my mind.

So, not only did I need to pick a textbook that could be accessed by a wide variety of students, it had to include the kind of timeless theology that would ideally spread wide and far. Bavinck fit the bill. Here are a handful of brief reasons why.

Bavinck was both Modern and Not

Herman Bavinck lived 1854-1921, which makes him, technically, a “modern theologian.” This is true not only in the sense that he fits within the post-enlightenment era, chronologically speaking, but also in the sense that he engages in modern ideas—the very same ideas that have, over the past couple centuries, shaped not only the Western world, but the world as a whole.[2]Bavinck’s modernity means that his language in Reformed Dogmatics, even with its being a translation, does not feel overly archaic and distant. His technical terminology is, roughly, the same as ours today, and the major theological ideas that were new for his day are still consequential for ours.

And yet, for all his modernity, he was also a theologian of the “one, holy catholic, and apostolic Church,” and was deeply situated in historical work. He had a clear grasp on where he was in the story God is providentially telling with the history of the Church, and he self-consciously stood in continuity with the people whom Lewis’s Screwtape describes (with a shudder) as “spread out through all time and space and rooted in eternity, terrible as an army with banners.”[3] This means that there are relatively no novelties in Bavinck. He is a small “c” catholic, Protestant and Reformed theologian, who hands his readers a hearty helping of orthodox theology. Further, Bavinck’s situatedness within the Great Tradition of Christianity means that his historical insights are significant and thorough. As a consequence, Bavinck functions as a “gateway” of sorts to many periods of church history that preceded him. When you get Bavinck, you get so much of Christianity down through the ages thrown in!Bavinck’s situatedness within the Great Tradition of Christianity means that his historical insights are significant and thorough. Click To Tweet

In other words, Bavinck is good for us because he is close enough to our age that he is contextually readable, and far enough away from our age that he is not bogged down with the awful and unfair burden of 20th century western theology—which is perhaps the very worst century for theology our world has ever known.[4] (I have decided to mercifully spare my students from that unfortunate period since there is relatively little to offer them that is worth repeating—we will essentially “skip” the 20th century.) Further, Bavinck is just far enough that he is a little bit difficult for all of us to read; he doesn’t include colloquial illustrations from contemporary American pop-culture or deploy idioms and figures of speech that are common to one culture and not another. In that sense, there’s a bit of a learning curve for all of us who read Bavinck, regardless of whether you are from Kansas City or Addis Ababa.

Bavinck Kept Theology Theological

Bavinck, like Owen and Turriten and Calvin and Aquinas and Anselm and Augustine and Athanasius before him, knew that theology was the study of God, primarily, and all things in relation to God, consequentially. This means that Bavinck did not fall prey to the tendency all-to-common among many theologians in the modern era (exemplified most intentionally and starkly in a figure like Tillich), which is to take our contemplative cues from the world around us and then project those concerns back up onto God. What happens when you develop a complete allergy to the metaphysics of classical thought—with its embrace of divine transcendence and a thorough-going grasp on the Creator-creature distinction? The Creator’s being and the creature’s being are flattened. God is domesticated, no longer being thought of as the transcendent Creator and sovereign Lord of history. In the tradition-despising metaphysic of the modern imagination, God is another character within history.Bavinck is good for us because he is close enough to our age that he is contextually readable, and far enough away from our age that he is not bogged down with the awful and unfair burden of 20th century western theology. Click To Tweet

The consequence of this way of conceptualizing theology is that theology becomes a procrustean bed; God must meet the needs we impose on him. Creedal formulations, within that ecosystem, are mangled. The language of orthodox Christianity is retained, but it is stripped entirely from its historical and metaphysical context. This is how it was possible for theologians across the board—conservative and progressive, fundamentalist and neo-orthodox, independent churches and mainline denominations—to project modern conceptions of “personhood” back up onto God, and to consequently conceptualize the Trinity’s unity as a unity of wills (skirting dangerously close to tritheism). This is how it was possible for Social Trinitarianism to dominate the theological landscape for nearly a century (whether such a “divine society” was deployed in service of hierarchy or socialism, complementarianism or egalitarianism, in the name of fundamentalist hatred for philosophy or in the name of post-enlightenment rationalism). This is how it was possible for theologians across the board to unilaterally dispense with crucial doctrines like divine simplicity, immutability, and impassibility. And Bavinck will have none of it.

Bavinck recognizes the metaphysical centrality of God’s nature. He recognizes that theology, so long as it is to keep its bearing, must keep itself about God, with God’s creation always in relation to him. The reason I prefer to give my students Bavinck instead of Grudem, in other words, is not merely because Bavinck would not project household roles of authority and submission back up onto God, but rather because he fundamentally resists the theological method that is hospitable to projecting anything back up onto God. Not only does he give us orthodox, Nicene Trinitarianism instead of EFS, he gives us the theological method that eventuates in the former and would never eventuate in the latter.

Bavinck was Richly Biblical

It’s important to emphasize what I mean. When I say “richly biblical” I want to contrast it both with a reductionistic or crude Biblicism on the one hand (more on that in just a moment) and a detached fanciful speculation on the other. Regarding the latter error, I want for my students to walk away from my class with an unabashed and unyielding love for the Scriptures. I don’t want them to use the Scriptures, but rather to live in them. To the degree that Bavinck will influence them, this kind of love for God’s word will inevitably be the fruit. Again, I am concerned not merely for what goes on in my classroom, but what will have staying power past my classroom—what will sustain years of faithful transmission of Christianity from one generation to another? Certainly not ideas that originate between my two ears! No, only the Word of God is sufficient to do that cross-generational work. Therefore, I want my students to have the impulse to lay deep roots in the Scriptures: roots that will continue to grow and receive renewed nourishment from the text over their lifetime. I want them to fully embrace the Reformation conviction of Sola Scriptura. Bavinck is as good a teacher and practitioner of that conviction as any.Because of his deep inhabitation within biblical reasoning, Bavinck did not merely describe or explore ideas—he confessed them. Click To Tweet

However, one of the reasons that Bavinck is such an able teacher and practitioner of Sola Scriptura is that he does so in a thorough and rich way, and not a reductionistic way. He is not “biblical” in the sense that he treats the Scriptures in a piecemeal fashion, excavating proof-texts and accumulating them into mounds that are summarized as doctrines willy-nilly. Rather, Bavinck shows us how to inhabit the Scriptures. Like how Lewis emphasizes in his brilliant essay, “Meditation in a Toolshed,” Bavinck demonstrates the crucial importance of not merely looking at (which is the reductionistic and Biblicist impulse to demand a chapter and verse for every doctrine), but also of looking along.[5] There is a difference between looking at a shaft of light as it shines through a hole in a toolshed’s roof and standing within the shaft of light and looking along its beam back up to its source. So too, there is a difference between looking at what a text says on the surface and looking along its reasoning to what it implies and necessitates about God and the world (its “good and necessary consequence,” as the Westminster Confession of Faith puts it). It is in that sense that doctrines like the Trinity, divine simplicity, Christ’s two natures, and membership are richly biblical. They are not “biblical” in the sense that they materialize in a chapter and verse, but rather in the sense that chapters and verses hang on them. Bavinck understood this.

Christian Dogmatics is Christian theology faithfully declared with proclamation force. Click To TweetThis richly biblical method is what lies behind the dogmatic mood of his writing. Because of his deep inhabitation within biblical reasoning, Bavinck did not merely describe or explore ideas—he confessed them. Christian Dogmatics is Christian theology faithfully declared with proclamation force. It is not merely a proposition of truth, but a proposition of truth that lays covenantal demands on both the speaker and the listener. The dogmatician concerns himself, most basically, with man’s chief end: the topic itself precludes cold indifference. Dogmatics, therefore, is not a mere intellectual exercise or academic play, it is rather worship (and to the degree that it isn’t, it falls short of being itself). This is why Bavinck’s dogmatics are not merely his recorded thoughts, they are his recorded praises. For all these reasons and more, I am looking forward to initiating my students into Bavinck’s Reformed Dogmatics, and I pray (and invite you to pray with me) it yields outsized fruit in the years to come.

Endnotes

[1] For example, a very important step towards my acceptance of the doctrines of grace came when I discovered Grudem’s Systematic Theology. In his section on divine Providence, he proceeded to lay out all of my Calvinist-rejecting reasons for denying God’s utter and exhaustive sovereignty over salvation, and then proceeded to graciously dismantle every single one of them. I will never be able to repay him for that timely theological beat-down. It saved my life.

[2] See Cory C. Brock’s work, Orthodox yet Modern: Herman Bavinck’s Use of Friedrich Schleiermacher(Lexham Press, 2020).

[3] C.S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters, letter 2.

[4] See Stanley J. Grenz and Roger E. Olson, 20th-Century Theology: God and the World in a Transitional Age (IVP Academic, 1992) for a retelling of the sad story of theology in this century.

[5] C.S. Lewis, “Meditation in a Toolshed,” in God in the Dock.