The Incorruptible Son has Clothed us with Incorruptibility

The passion of our Lord is nearly upon us, which has galvanized me to return to the incarnation and ask that ancient question, why did God become man? As you can imagine, this question is at the core of the Systematic Theology I am writing for Baker Academic. As I’ve chewed on this question, I have noticed that more often than not our default answer is a legal one. That is as it should be. In the vein of Romans 5, in Adam we face condemnation. What would original sin be if we emptied the doctrine of guilt? Singing in the forensic key summons Christ whom Paul says is not only the wisdom of God but the righteousness of God. Why did God become man? Surely for the sake of a great, most happy exchange. In Adam, we failed to obey God’s good law, but the second Adam is spotless, tempted yet without sin, fulfilling the law not in part but in whole, all so that his righteousness can be imputed to you and me upon faith. However, our Lord is not only spotless but the spotless lamb. Behold, the lamb of God, said John the baptizer. In Adam, we have broken God’s law, becoming transgressors. But the lamb has been sacrificed, bearing the full weight of divine judgment for the forgiveness of our sin. We sing with Isaiah that our suffering servant was “pierced for our transgressions” and “crushed for our iniquities”—the lamb has become the guilt offering to “make many to be accounted righteous.”To end there is to cut short the mystery of the incarnation. Click To Tweet

I am tempted at this point to shout out a hearty, Amen! But that would be premature. To end there is to cut short the mystery of the incarnation. As I said, the forensic tends to be our forte, but the full mystery must account for our fallen nature as well. If our doctrine of original sin is well-rounded, then we not only have received Adam’s guilt, but we are the inheritors of his corrupt nature as well. It is odd that we forget the devastating status of our Adamic nature during passion week when our everyday existence bears its marks, from the inner disposition of our nature towards wickedness to the unrelenting mortality of our body. Creation groans and our nature with it.

Have we forgotten that Genesis 3 was a fall? The Fall was a descent. For Adam disrupted his participation in the likeness of his Creator who is goodness without measure. Our first father soon discovered that his failure to participate—deceived as he was by the dazzling allure of autonomy—was evil and, if that which is “good is being,” then that which is “evil is non-being.” That language is not my own but belongs to Athanasius. In fact, this language launches his classic, On the Incarnation. “For the human being is by nature mortal, having come into being from nothing. But because of his likeness to the One who Is, which, if he had guarded through his comprehension of him, would have blunted his natural corruption, he would have remained incorruptible,” says Athanasius. You can almost hear the sigh in Athanasius’s voice. If only. If only Adam had steadied his gaze on God, the image of God he bore would not have been corrupted. But Adam traded being for non-being, participation for exile, life with God for a tomb.But Adam traded being for non-being, participation for exile, life with God for a tomb. Click To Tweet

Therefore, God became man “to bring the corruptible to incorruptibility.” And who else to return us to being but the Word “who in the beginning made the universe from non-being?” Anticipating Maximus the Confessor, Athanasius introduces us to the cosmic mystery of Christ’s incarnation: “Being the Word of the Father and above all, he alone consequently was both able to recreate the universe and was worthy to suffer on behalf of all and to intercede for all before the Father.” And, anticipating John Calvin, Athanasius can introduce the incarnation as a condescension: “condescending to our corruption…he takes for himself a body and that not foreign to our own.” Born of a woman, the body of Christ becomes instrumental (Athanasius’s word) to this end. In one of his most potent paragraphs, Athanasius says,

Although being himself powerful and the creator of the universe, he prepared for himself in the Virgin the body as a temple, and made it his own, as an instrument, making himself known and dwelling in it. And thus, taking from ours that which is like, since all were liable to the corruption of death, delivering it over to death on behalf of all, he offered it to the Father, doing this in his love for human beings, so that, on the one hand, with all dying in him the law concerning corruption in human beings might be undone (its power being fully expended in the lordly body and no longer having any ground against similar beings), and, on the other hand, that as human beings had turned towards corruption he might turn them again to incorruptibility and give them life from death, by making the body his own and by the grace of the resurrection banishing death from them as straw from fire.

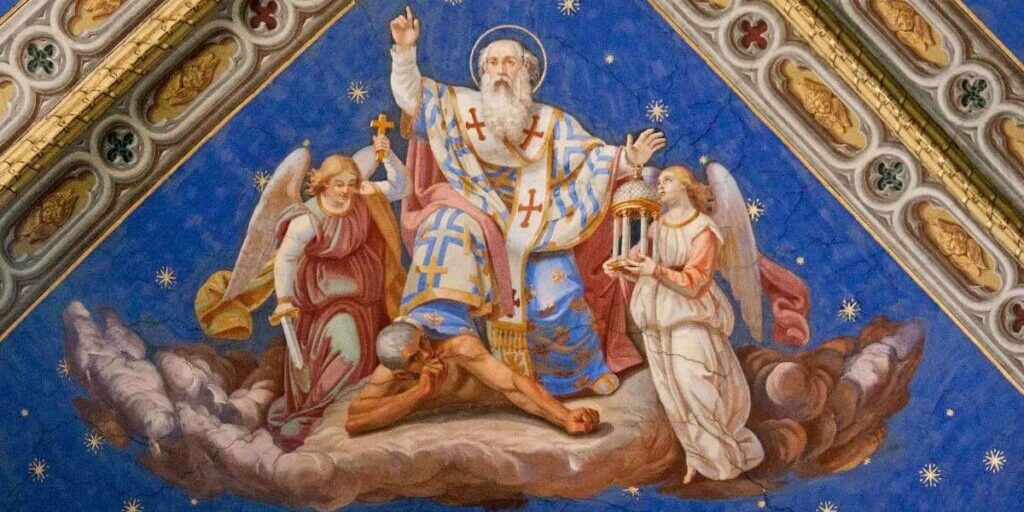

I rarely hear the incarnation described this way today, which makes me wonder if we have short-circuited the gospel by failing to mention that the Incorruptible One himself has borne our flesh to heal our nature. The “incorruptible Son of God consequently clothed all with incorruptibility”—this is how Athanasius describes the gospel.We need not sever the legal from the transformative. Click To Tweet

If Athanasius is right—and Hebrews 2:9-10 tells me he is—then we need not sever the legal from the transformative. For Christ has come not only to remedy our guilt but our corruption. By means of his passion and resurrection we share—participate—in the incorruptibility of the Incorruptible Son. I think Athanasius would have loved the title of John Owen’s treatise: the death of death in the death of Christ. Or as Athanasius says, we would have “been utterly dissolved” if the Son himself had not “come for the completion of death.” But he has come so that by his wounds we might be healed (Isa. 53:55). In Adam the image of God was corrupted; in Christ the image of God has been renewed. For this reason, God became man: “So he rightly took a mortal body, that in it death might henceforth be destroyed utterly and human beings be renewed again according to the Image. For this purpose, then, there was need of none other than the Image of the Father.”

Well, as you can tell I have been immersed in Athanasius and the author of Hebrews and I am struggling to get out. But when I have escaped their company, here are others I have been talking with:

I taught the Philosophical Theology PhD seminar this semester and I know I say this each time but with every passing year this seminar becomes one of the richest dialogues I have with students. Why is this? There may be many reasons, but I think one of them is this: students are starving for a robust, realist metaphysic that can substantiate their classical theology.

God should be contemplated in community—hence, the communion of the saints. The Credo Alliance met twice and this time in person. We usually put these conversations up on the Credo podcast, but this time we also captured video. The first conversation is about the procession of the Holy Spirit and in the second conversation we share our first encounters with Thomas Aquinas. Fred Sanders, Scott Swain, JV Fesko, and I share our stories. Watch both videos here.

In other news, very soon we will open registration for the Center for Classical Theology lecture this November in San Diego. Michael Horton will be delivering this annual lecture, and he has told me to title his lecture, “If Reformed, then catholic: Sola scriptura revisited.” What a time of fellowship with like-minded brothers and sisters this will be. Check CCT to register soon.

Last, after this spring semester I go on sabbatical. Pray for me as I will be devoting this next year to writing this Systematic Theology.

This post is originally from Matthew Barrett’s regular newsletter. Subscribe here and receive updates on his research for his Systematic Theology.

Image by Lawrence OP