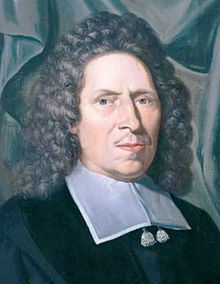

Petrus van Mastricht lived from 1630-1706. He was both a pastor and a professor in the Netherlands. Living after the Synod of Dort, Mastricht retrieved the tools of medieval scholasticism for the purpose of codifying the Reformed faith. His great achievement is his Theoretical-Practical Theology, now available at Reformation Heritage Books.

The following except is brief but nonetheless a fine example of Mastricht’s use of scholastic vocabulary and methods to advance his Reformed articulation of God’s decree, exhibiting even in a short amount of space his engagement with both classical philosophy, the church fathers, and the medieval scholastics. Of special import is Mastricht’s use of classical theism as articulated by the fathers and scholastics to refute Arminianism and Socinianism. Furthermore, the format (quaestio) is itself a scholastic technique that Mastricht utilizes and the rest of his treatment (not provided here) also exhibits the scholastic method as Mastricht answers objections.

At the end of this except we also provide an interview with Ryan McGraw where he explains why pastors should engage Mastricht.

Petrus van Mastricht: On God’s decree and divine simplicity

The Elenctic Part

It is asked: 1. Is the decree of God his very essence? The difference of opinions

XXVIII. It is asked, first, whether the decree of God is his very essence. Among the Greeks the question was once raised whether the essence and will of God were the same thing, with some denying and affirming, as is apparent in Justin Martyr, or whoever is the author of the book Questions for the Greeks. Concerning this question subsequent fathers, especially Augustine in his book On the Essence of God, and likewise the Scholastics, John of Damascus, Lombard, Aquinas, and others, responded in the affirmative. The Remonstrant Apologists, so that they may have the Sicilians more favorable to them, and so that they may more strongly impugn the simplicity of God and more easily obtain the mutability of the divine decrees, deny it. The Sicilians more openly deny it and refer to accidents in God, to the end that they may overturn the simplicity of God, and his immutability. The Reformed acknowledge that the things decreed differ essentially from the divine essence, and likewise that the tendency of the decree indefinitely toward some object is not indeed the very essence of God, but yet is for the constitution of the decree entirely required, because otherwise there would be a decree that decreed nothing. However, with respect to the act of decreeing, they acknowledge that the decree is the same as the essence, except that considered absolutely and in itself the essence does not connote the tendency toward this or that object which the decree formally considered implies. From this there are not lacking among the Reformed those who distinguish between the essence and the decree, yet in this way, that thereby they do not allow any composition in God, because that tendency is nothing except a relation, which properly speaking has no entity whereby it could make him composite.

The reasons

The reasons of the Reformed, whereby the decree is the same thing as the essence of God, are sought: (1) from the divine simplicity, through which he rejects all accidents, just as we demonstrated in its own place in the chapter on the simplicity of God; (2) from his infinity, which does not allow a difference of things, or parts, or any composition, as we showed in its own place; (3) from the fact that the decree in God is nothing except his intellect and will, which without a doubt coincide with his essence; (4) because accidents, which by their nature imply imperfection, do not square with the most perfect one.

Why should pastors should engage Mastricht?

Ryan McGraw

I have been warmly commending, Peter van Mastricht’s Theoretico-Practica Theologia for a decade. However, students have wondered whether my promises that someone was translating it into English were empty. Now that these promises are finally coming to fruition with the publication of this first volume, as one pastor asked me, “Why should I buy and read another systematic theology?”

One answer is to appeal to the glowing endorsement of the book from Jonathan Edwards, which is included on the back cover. Comparing Mastricht with Turretin, he noted, “they are both excellent.” Yet he added that Turretin was fuller on controversial points while Mastricht was better on the whole as a “universal system of divinity.” This led him to say that, as a whole, this book “is much better than Turretin or any other book in the world, excepting only the Bible.”

While a commendation from such a great luminary like Edwards will be enough to sell the set to many, others need more incentive. Below are four reasons why pastors should both buy Mastricht and not let him collect dust on their shelves. I will conclude with some suggestions on how to use this work in the ministry.

1. Mastricht’s theology is for preachers.

While modern pastors and students likely will not (and should not) adopt Mastricht’s exact method of preaching, they should learn from his goals. Today, it is common for men either to be academic theologians or to labor for the church without seeing any relevance of academic theology to the ministry of the local church. In the period known as Reformed orthodoxy, many ministers wedded a precise academic theology with the devotional needs of local congregations. The skill of translating content back and forth between these realms has become rare. Mastricht wrote his theology with scholastic precision without losing sight of the ministry and piety. This process should be a vital component of training pastors in every age.Mastricht wrote his theology with scholastic precision without losing sight of the ministry and piety. This process should be a vital component of training pastors in every age. Click To Tweet

2. Mastricht’s system is comprehensive.

Mastricht wove exegesis, systematic theology, elenctic theology, and practical theology into a single system. He had something approaching the precision of Turretin and the devotion of Brakel. However, he neither reached the same level of precision as Turretin nor the same depth of devotion as Brakel. Yet few authors do everything that Mastricht does in a single volume. Turretin’s elenctic theology is fuller than Mastricht’s, but Mastricht includes it. Brakel’s pastor counsel is more robust than Mastricht’s, but he does not neglect it. At the same time, Mastricht’s exegetical and positive treatments of theology outstrip both of these other authors. While many classic Reformed authors included aspects of each of Mastricht’s four divisions in their theological systems, he is the only one that this author knows of that divided each chapter of his theology into these categories. This makes his work more comprehensive than most.

3. Mastricht’s theology is exegetical.

Some readers enjoy the devotion of Brakel’s Christian’s Reasonable Service only to be disappointed with the quality of his biblical exegesis at points. Every author has strengths and weaknesses. While Mastricht’s devotional sections are not as searching or extensive as Brakel’s, his engagement with Scripture is often more satisfying. A good example is his treatment of the covenant of grace from Genesis 3:15. He drew out the idea that in the text there is a singular Seed of the woman and a corporate seed of the woman, both of which stand in opposition to the Serpent (singular) and his seed (plural). He thus established the union between Christ and his people in the application of the covenant of grace and showed the contrast and conflict between the church and the world. The basic ideas of his treatment of the covenant of grace as a whole were embedded in his exposition of this text. This pattern is true in virtually every chapter of his work. This feature not only makes modern readers grapple with and remember key passages of Scripture related to each doctrine. It gives us a window into understanding early-modern approaches to interpreting Scripture more fully. This is important because it represents a model of biblical interpretation that was unafraid of drawing theological conclusions and applications from Scripture, which can provide a refreshing challenge and compliment to modern biblical interpretation.

4. Mastricht’s theological system promotes devotion to the triune God.

People do not frequently associate scholasticism with piety. Yet Reformed scholastic theological, such as this one, wove communion with God directly into their definitions and practice of theology. While earlier authors such as Junius, Polanus, and Wollebius addressed the godly character of the theologian in tandem with the nature of true theology, theologians of the Dutch Second Reformation often developed the practical implications of theology more fully. This is most obvious in one of Mastricht’s teachers, Johannes Hoornbeeck, who wrote a theological system dedicated exclusively to bringing out the practical implications of each doctrine. Mastricht falls solidly into this tradition. He frequently organized his praxis sections around the four uses of Scripture listed in 2 Timothy 3:16-17. He defined theology as the doctrine of living to God through Christ (per Christum). This makes it clear that the aim of theology was to know the right God in the right way, which is through Christ as the only Mediator between God and man. The Spirit makes this possible by using divinely ordained means to bring us to Christ and to make us like him.

The trinitarian devotion implied in his definition of theology carries through the entire work. Mastricht devoted a distinct chapter to each divine person as well as one to the doctrine of the Trinity more broadly. He also self-consciously wove the glory of the triune God into every locus of theology. While such trinitarian reflection and devotion was rare in English literature during the seventeenth-century, the Dutch concern over the Arminianism marginalization of the Trinity, who denied that the Trinity was a fundamental article of the faith, promoted a more robust use of the doctrine. Although academic theologians are giving increasing attention to the Trinity, these reflections rarely reach the average pastor, let alone Christians more broadly. This makes Mastricht’s way of doing theology is both timely and refreshing.

Read Mastricht and grow in your affection for the Triune God and his Word

Most Latin Reformed theology will never be translated into English, but Peter van Mastricht’s Theoretical-Practical Theology certainly deserves to be. After buying Mastricht, how do you prevent it from collecting dust on your shelves? The best way is to plan how you will use it and when. This could involve breaking the work into segments that you can read one week at a time until you finish it. Some have done this with works, such as Bavinck, and have included friends to make it more profitable. You can also read sections based on what you are doing. For example, pastors the sacraments regularly. Pick up Mastricht on this subject next time you prepare for a baptism or the Lord’s Supper (once this volume is translated). Or, read Mastricht on the Trinity while you are preaching through John’s gospel, or on the attributes of God while preaching through the OT. Doing so prayerfully and regularly can only enrich and deepen your ministry. However you choose to read Mastricht, read him to grow in your affection for the Triune God and his Word. Let us show our gratitude to God who is providentially making this great work available to us in English by taking advantage of it in our studies.