The theological world is currently abuzz with debates concerning the legitimacy, method, and limits of theological retrieval. Although theological retrieval may be a broad topic referring to a multiplicity of movements, the basic premise acknowledges that Christians are reaching back into history for pre-modern sources to help them navigate modern and postmodern theological dilemmas.[1] In many ways, this is nothing new, as learning from great thinkers of the past is one way that the Church has always attempted to “contend earnestly for the faith that was once for all time handed down to the saints” (Jude 1:3). Church history, however, is broad and includes an eclectic (to say the least) cast of characters, many of which seem unfamiliar or even strange to contemporary protestants. So, the question must be asked – whose theology should we intend to retrieve? Or, as one guest at a recent panel discussion on the matter phrased it, “Who’s in? Who’s out? Who makes the cut?”

Why did Protestants since the Reformation retrieve Aquinas?

There may be perhaps no greater controversial figure within the evangelical protestant movement of theological retrieval than Thomas Aquinas. My first systematic theology professor made his stance very clear: Thomas was a heretic who should only be read with the utmost caution and the highest degree of skepticism. If you found yourself agreeing with Thomas, then you simply had not read enough of Martin Luther!

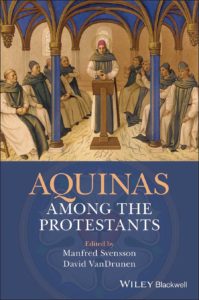

While this is a common refrain echoed by many evangelicals, others have taken a more amicable, yet critical, approach to the “happy doctor.” According to the authors of A quinas Among the Protestants, the latter approach is not only recommended but exemplified throughout Protestantism since the Reformation. The contributors of AAP examine a few test cases highlighting when protestants have historically accepted, modified, or rejected aspects of Thomas’s theological conclusions while providing a helpful framework for contemporary Protestants to engage in critical dialogue with Thomas in the future.

quinas Among the Protestants, the latter approach is not only recommended but exemplified throughout Protestantism since the Reformation. The contributors of AAP examine a few test cases highlighting when protestants have historically accepted, modified, or rejected aspects of Thomas’s theological conclusions while providing a helpful framework for contemporary Protestants to engage in critical dialogue with Thomas in the future.

To that end, the work is separated into two sections, the first of which focuses on historical examples of Protestants positively engaging with Thomas’s work. Readers are here introduced to a wide array of figures such as Protestant reformers like Peter Martyr Vermigli and Jerome Zanchi, Anglicans Richard Hooker and William Whitaker, Dutch Reformed theologian Herman Bavinck, and even German theologians such as Wolfhart Pannenberg and Eberhard Jüngel. Although each contributor focuses on a different aspect of Thomas’s theology, a consensus begins to emerge. Once a historical investigation of reformational thought moves beyond an analysis of Martin Luther to a wider variety of reformed thinkers, an eclectic appropriation of Thomas Aquinas begins to appear.[2]Protestants have positively engaged with Thomas Aquinas, including reformers like Peter Martyr Vermigli and Jerome Zanchi, Anglicans like Richard Hooker and William Whitaker, and Dutch Reformed theologian Herman Bavinck. Share on X

Within this first section, the chapter I most strongly recommend is David Sytsma’s “Thomas Aquinas and Reformed Biblical Interpretation: The Contribution of William Whitaker” (49-74). Thomas’s bibliology is a consistent source of both critique and caricature within the critical stream of evangelicalism. Anyone familiar with Sytsma’s other academic works will not be surprised to read that he masterfully demonstrates Thomas’s reliance on exegesis and concludes that there exists a greater continuity between Thomas’s hermeneutic and later reformed hermeneutics than is often appreciated. If inroads are to be made between contemporary Protestants and the thought of Thomas Aquinas, then conclusions of the two camps regarding biblical exegesis, hermeneutics, and scriptural authority must be compatible. Sytsma shows that this is indeed the case, thus opening the door for further dialogue.

Positive Engagement with Thomas Aquinas

The second section of AAP focuses on a sampling of Thomistic concepts which offer hope for positive evangelical engagement. As such, the second part of the book will benefit those readers who may be more conceptually minded than historically minded. It is one thing, after all, to demonstrate that Protestant thinkers in the past have benefitted from Thomas, but it is another matter entirely to prove that they should have done so.[3]

Topics within this section reflect a helpful variety including metaphysics, the relationship between nature and grace (in which John Calvin makes a surprising appearance), ethics, and even a chapter on justification which may surprise or even alarm some readers.[4] Again, if I could only recommend one chapter within this section I must point them to Scott Swain’s, “On Divine Naming” (207-228). Readers who are familiar with Thomas’s work, specifically the Summa Theologiae, will know that the question on divine names is where Thomas introduces the concept of analogical language, a topic ripe for metaphysical investigation and a source of consistent critique against Thomas. Swain guides his readers through difficult but enriching concepts such as prepositional metaphysics, archetypal and ectypal theology, and natural theology to demonstrate that “metaphysical and personal modes of divine naming belong together in the Christian doctrine of God” (223). In so doing, I believe Swain paves the way to address much of the popular criticisms brought against Thomas by such influential Protestant thinkers as Cornelius Van Til, Gordon Clark, or Carl F.H. Henry, albeit without naming any of them.

More engagement

Much within the theological works of Thomas and the teachings of early Protestants which he influenced are all worthy of theological retrieval. Share on XThe biggest potential weakness of the book is the limited inclusion of explicit critique against Thomas. It is true that criticism from thinkers such as Martin Luther and the “Calvin against the Calvinists” movement are addressed throughout the book, but Protestant hostilities towards Thomas are not limited to those thinkers. Indeed, some of the more vocal critics against Thomas today are self-proclaimed Van Tillians, but neither Van Til nor his objections against Thomas make an appearance in the book, despite there being an entire chapter dedicated to Dutch Reformed thought (129-148).[5]

Now, as I stated earlier, many of the concepts addressed in the book highlight these provocative topics, which will prove useful to readers who are already aware of controversies, but these connections may be overlooked by readers with limited knowledge of prior debates. Further still, readers can hardly expect for every topic, debate, or personal theologian-of-choice to make an appearance in a book designed to provide a bird’s eye view of an expansive topic, so readers should be aware that, as far as weaknesses go, this is a mild critique.

The strengths of this work, however, are legion. It is, of course, a collection of essays so accessibility will vary from chapter to chapter, but overall, the contributors have successfully introduced readers to difficult concepts in understandable prose. This is unsurprising, of course, when one looks at the pedigree of the contributors including not only thinkers previously mentioned such as David Sytsma and Scott Swain but also influential theologians and historians such as J. V. Fesko, John Bolt, Michael Allen, Paul Helm, and editors Manfred Svensson and David VanDrunen.

In short, readers unfamiliar with Thomas and his influence on reformational thought may pick up AAP and find numerous qualified and trustworthy guides to lead them through an unknown land. In so doing, we will find that much within the theological works of Thomas and the teachings of early Protestants which he influenced are all worthy of theological retrieval.

Endnotes

[1] For a brief overview of various movements attempting theological retrieval across the denominational spectrum see Michael Allen and Scott R. Swain, Reformed Catholicity: The Promise of Retrieval for Theology and Biblical Interpretation (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2015), 1-15.

[2] This is not to suggest that it is entirely accurate to portray Luther’s relationship with Thomas as completely negative. Indeed, Luther described Thomas’s works positively throughout his writing career, yet, in true Luther fashion, lambasted Thomas when he felt it appropriate. For an overview of Luther’s relationship with Thomas Aquinas see Christoph Schwöbel, “Reformed Traditions,” in The Cambridge Companion to the Summa Theologiae, edited by Philip McCosker and Denys Turner (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 319-342.

[3] For instance, a popular movement known as “Calvin Against the Calvinists” has suggested that the Thomistic influence within protestant scholasticism was a departure from the pure biblical reasoning of John Calvin. The thinkers involved with this movement would acknowledge but lament a Thomistic influence within Protestantism. It should be noted, however, that the historical merit of this movement has been questioned in recent analysis and shown to be untenable. For more info see Jordan J. Ballor, “Deformation and Reformation: Thomas Aquinas and the Rise of Protestant Scholasticism,” in AAP, 28-38.

[4] J.V. Fesko’s chapter on justification provides opportunity to direct readers to another helpful source on the same topic. For more information concerning how protestants may adapt Thomas’s understanding of justification for evangelical theology see Christopher Cleveland, Thomism in John Owen (New York: Routledge, 2016), 69-120.

[5] Harrison Perkins makes a similar critique in his review of AAP. See Harrison Perkins, “Review of ‘Aquinas Among the Protestants,” in Scottish Bulletin of Evangelical Theology 36.2 (Autumn 2018): 183-185.