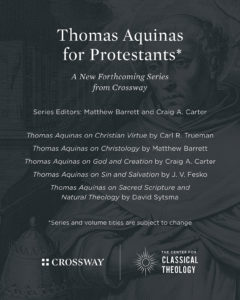

If we listen to the noisy din of some self-professed Protestants, medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas should be left to the dustbin of history because his doctrine stands at odds with the teaching of scripture and the solas of the Reformation. On a host of issues ranging from faith and reason, to salvation, to last things, Aquinas is best forgotten. Even though some make these claims, when we dig into the assessments of various early modern Protestant theologians, a very different picture emerges. Rather than cancel culture theology, early modern theologians were nuanced in their twofold appropriation of Aquinas. On the one hand, they rejected teachings that contradicted scripture. On the other hand, they positively employed insightful teachings.

To illustrate and confirm this claim, this brief essay examines John Owen’s (1616-83), the Westminster Assembly’s, and the Synod of Dort’s continuities with Aquinas on the doctrine of salvation. These theologians and assemblies excised the problematic teachings of infused righteousness as it relates to justification but retained Thomas’s teaching on infused habits for the doctrine of sanctification. This essay first proceeds to examine Aquinas’s doctrine, then explores how Reformed theologians like John Owen utilized his categories in a nuanced way, and finally assesses the benefits of such a careful retrieval of Aquinas.

Aquinas on Justification

I n his Summa Theologicae Aquinas proposes that there are four parts to the doctrine of justification: (1) the infusion of grace, (2) movement of freewill towards God by faith, (3) movement of freewill against sin, and (4) the remission of sin.

n his Summa Theologicae Aquinas proposes that there are four parts to the doctrine of justification: (1) the infusion of grace, (2) movement of freewill towards God by faith, (3) movement of freewill against sin, and (4) the remission of sin.

The infusion of grace is the cause of everything else that follows in justification.[1] According to Aquinas the infusion of grace is the implantation of a divinely given habit, or disposition.[2] Aquinas distinguished between an acquired habit, which is something that Aristotle argued was the result of training. In other words, you obtain the acquired habit (or disposition) of bowling well the more that you practice the sport. Medieval theologians like Aquinas, however, distinguished between an acquired versus infused habit. An acquired habit comes from within humans whereas an infused habit comes from without, from God. By God’s grace the Spirit infuses a habit of justifying faith in a person so that he is positively disposed towards righteousness. The righteousness of faith can either increase or decrease, according to Aquinas.[3]

People receive this infused habit of faith at baptism, increase and grow in righteousness, until they are actually righteous and are thus finally justified by God. In short, unlike later Protestants Aquinas does not distinguish between justification (the legal forensic act) and sanctification (the work of God’s grace whereby he conforms us to the image of Christ).

John Owen’s Retrieval of Aquinas

Despite Aquinas’s conflation of justification and sanctification, Protestant theologians like John Owen took a nuanced approach to Aquinas’s doctrine of justification. Owen rejected the idea of infused righteousness for justification. He, like other Protestant theologians, believed that Scripture teaches that God justifies sinners by the imputed righteousness of Christ rather than infused righteousness. But just because he rejected infused righteousness in justification did not mean that he totally rejected the category. Owen writes:Rather than cancel culture theology, early modern Reformed theologians were nuanced in their twofold appropriation of Aquinas. Click To Tweet

That there is an habitual infused habit of Grace which is the formal cause of our personal inherent Righteousness they grant. But they all deny that God pardons our sins, and justifies our persons with respect unto this Righteousness as the formal cause thereof. Nay they deny that in the Justification of a sinner there either is, or can be any inherent formal cause of it. And what they mean by a formal cause in our Justification is only that which gives the denomination unto the subject, as the Imputation of the Righteousness of Christ doth to a person that he is justified.[4]

Owen readily grants that Reformed theologians affirm the reality of an infused habit of grace and that this infused righteousness is the formal cause of a person’s inherent righteousness. He stipulates, however, that this inherent righteousness is not the legal ground of a believer’s justification. Rather, the perfect imputed righteousness of Christ is the legal ground and formal cause of a person’s justification. How does Owen hold the concepts of imputed and infused righteousness together? How does he blend this Thomist category of the infused habit of righteousness together with the Reformation teaching of justification by the imputed righteousness of Christ?

The Reformed confessional tradition sheds greater light upon the compatibility between imputed versus infused habits of righteousness. The Westminster Confession’s explanation of justification rejects the concept of infused righteousness (11.1).[5] The Confession then explains, “Faith, thus receiving and resting on Christ and his righteousness, is the alone instrument of justification; yet is it not alone in the person justified, but is ever accompanied with all other saving graces, and is not dead faith, but worketh by love” (11.2). The Confession acknowledges that the “principal acts of saving faith are accepting, receiving, and resting upon Christ alone for justification, sanctification, and eternal life” (14.2).

But at the same time faith “worketh by love” (11.2). In other words, in justification faith is passive as it receives the imputed righteousness of Christ, but in sanctification it is active and works by love (Gal. 5:6). The Westminster Larger Catechism explains the difference between justification and sanctification when it asks how they differ: “Although sanctification be inseparably joined with justification, yet they differ, in that God in justification imputeth the righteousness of Christ; in sanctification his Spirit infuseth grace, and enableth to the exercise thereof” (q. 77).

In the Larger Catechism’s definition of sanctification, the divines continue to employ the language of infused habits when they write: “Having the seeds of repentance unto life, and all other saving graces, put into their hearts, and those graces so stirred up, increased, and strengthened, as that they more and more die unto sin, and rise unto newness of life” (q. 75). This sounds a lot like Aquinas’s doctrine of justification as the believer increases in righteousness, but the difference here is that this growth does not factor in justification, which rests entirely upon Christ’s imputed righteousness. In justification the infused habit of faith is passive but in sanctification it is active. What Aquinas conflates Owen and the Westminster divines distinguish. Even though they distinguish justification and sanctification, they nevertheless maintain they are inseparably joined together.In justification the infused habit of faith is passive but in sanctification it is active. Click To Tweet

The Westminster divines were not alone in affirming these concepts, as the Synod of Dort (1618-19) also commends them. In their rejection of errors under the doctrinal head that treats human corruption, the Synod rejected those

Who teach that in the true conversion of men and women new qualities, dispositions, or gifts cannot be infused or poured into their will by God, and indeed that the faith [or believing] by which we first come to conversion and from which we receive the name “believers” is not a quality or gift infused by God, but only a human act, and that it cannot be called a gift except in respect to the power of attaining faith.

For these views contradict the Holy Scriptures, which testify that God does infuse or pour into our hearts the new qualities of faith, obedience, and the experiencing of his love: “I will put my law in their minds, and write it on their hearts” (Jer. 31:33); “I will pour water on the thirsty land, and streams on the dry ground; I will pour out my Spirit on your offspring” (Isa. 44:3); “The love of God has been poured out in our hearts by the Holy Spirit, who has been given to us” (Rom. 5:5). They also conflict with the continuous practice of the Church, which prays with the prophet: “Convert me, Lord, and I shall be converted” (Jer. 31:18) (Canons of Dort, III/IV, rej. of errors VI).

The Benefits of Nuanced Retrieval

The Reformed retained the idea of an infused habit of righteousness for sanctification but rejected it for justification. Click To Tweet John Owen, the Synod of Dort, and the Westminster divines plied Aquinas’s insights but did not simply repristinate them. They distinguished justification and sanctification and thus retained the idea of an infused habit of righteousness for sanctification but rejected it for justification.

But of what benefit is the concept of an infused habit? Owen points out two important benefits that employing the concept of infused habits in sanctification brings to the doctrine of salvation.

First, infused habits help us distinguish between natural human ability from those abilities given by the grace of God in salvation. Remember, acquired habits accrue in a person by repetition or conversely decrease by the cessation of the practice of the habit, whereas an infused habit comes from God by the work of the Holy Spirit. Participation in the divine nature by union with Christ is the source of all true holiness, according to Owen.[6] Thus, by acknowledging that a capacity for holiness and righteousness is infused is another way of saying that it is the gift of God.

Second, the infused habit of faith establishes a conceptual context for a theology of virtue. What is virtue? The chief theological virtues are faith, hope, and love. Owen observes that some people might perform virtuous acts and duties of obedience from their own natural habits rather than the infused habit of God’s grace. Someone might give alms to the poor, but if the action comes from their own naturally acquired habit, then their motivation might be self, merit, reputation, praise, compensation, or a host of other reasons except for the proper motive, which is the glory of God in Christ.

Virtue, therefore, must arise from the indwelling power and work of the Spirit (the infused habit), not a person’s natural abilities. But an infused habit can be preserved, increased, strengthened, and renewed.[7] In other words, echoing biblical concepts articulated by Aquinas, the Westminster Confession contends that saints can “grow in grace, perfecting holiness in the fear of God” (13.3).[8]

One of the greatest benefits of recovering infused habits lies in retrieving the concept of virtue. Click To Tweet One of the greatest benefits of recovering infused habits lies in retrieving the concept of virtue, a once common staple in Reformed treatments of sanctification and ethics. With the more recent modern rejection of infused habits by the likes of Karl Barth (1886-1968), virtue ethics fell to the wayside. Greater attention fell upon command ethics and expositions of the law of God. We must, of course, exposit and understand the law of God, but not at the expense of understanding how we can practice and grow in virtue. God not only made a covenant with Abraham and swore a self-maledictory oath to bear the curses on his behalf and thus save him (Gen. 15), but he also told Abraham, “Walk before me, and be blameless” (Gen. 17:1).

No cancel-culture theology

In the present day there are many within the church who have been swept up in the all-or-nothing approach of the world. Either you get everything right down to the smallest jot and tittle, or everything you say is suspect and wrong. We see this in cancel culture, but we cannot embrace this type of approach in theology. No one person is one hundred percent accurate in their theology. Even as redeemed sinners on our best days we still misunderstand or unintentionally misrepresent the teaching of scripture. Thus, Reformed theologians of the past exercised a principled eclecticism where they embraced a theological position insofar as it conformed to scripture and then excised the bits that did not fit.The Reformed tradition did not repristinate Aquinas’s doctrine of salvation but retained the elements they believed accurately traced the teaching of scripture. Click To Tweet

They did not, therefore, repristinate Aquinas’s doctrine of salvation but retained the elements they believed accurately traced the teaching of scripture. In this case, they rejected infused habits for justification but retained them for sanctification and even incorporated them into their confessional tradition. This means that we have much to learn from theologians of the past, and like our Reformed forebears, we need to be willing to come to theologians of the past, humbly listen, and learn from them. This does not mean surrendering our commitments to sola Scriptura, as the “Holy Spirit speaking in the Scripture” is the “supreme judge by which all controversies of religion are to be determined, and all decrees of councils, opinions of ancient writers, doctrines of men, and private spirits, are to be examined” (WCF 1.10). But at the same time, we can take learned insights from theologians like Aquinas’s infused habits and ply them to great benefit so long as we norm these insights by Scripture as theologians like Owen and the divines at Dort and Westminster did.

Endnotes

*This essay is a simplified version of “Aquinas’s Doctrine of Justification and Infused Habits in Reformed Soteriology,” in Aquinas Among the Protestants, ed. David VanDrunen and Manfred Svensson (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2018), 249-66.

[1] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica (Allen, TX: Christian Classics, 1948), IaIIae 133.8.

[2] Aquinas, Summa Theologica, IIaIIae 4.1.

[3] Aquinas, Summa Theologica, IaIIae, 52.1; 53.2.

[4] John Owen, The Doctrine of Justification fy Faith Through the Imputation of the Rightouesness of Christ (London: R. Boulter, 1677), 82.

[5] All confessional quotations come from Jaroslav Pelikan and Valerie Hotchkiss, eds., 3 vols. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003).

[6] John Owen, Pneumatologia (London: Nathaniel Ponder, 1674), 416.

[7] Owen, Pneumatologia, 417.

[8] Cf. Aquinas, Summa Theologica, IaIIae 54.4.