Before Paradise Lost became the supreme literary book of my life during my first year in graduate school at the University of Oregon, I was a totally unlikely candidate for it to happen. For reasons unknown, during my sophomore year in high school my English teacher challenged me to read Paradise Lost during Christmas vacation. I did so out of respect for my teacher. Being a farm boy from an unsophisticated immigrant subculture, I lacked the antennae by which to receive what the poem offered.

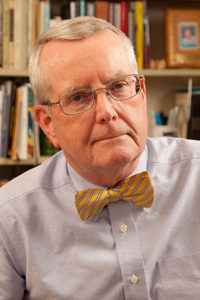

A Farm Boy Becomes a Miltonist

For additional unknown reasons, I did not read Milton during my

college years as an English major. Knowing that the chair of the English Department at the University of Oregon was one of the foremost Milton scholars in the world, I read the poem in a scholarly edition during the summer preceding my enrollment in graduate school. When I arrived on campus with a month to spend in self-directed study, the providential unfolding of events led me to purchase a copy of C. S. Lewis’ book A Preface to Paradise Lost in the campus bookstore. By the time I took my first Milton course that fall, I was primed to become what in my profession is called a Miltonist. I share this background to my life with Paradise Lost because it illustrates an important fact of many people’s literary experience, namely, that their encounter with literature is deeply influenced by their formal education. It is a work that possesses what C. S. Lewis taught me to call line by line deliciousness. Share on X

The Converting Power of Paradise Lost

I wrote my dissertation on Paradise Lost, and I have published books and articles on it. Out of the mass of commentary that I have absorbed on Milton’s masterpiece, my very favorite sentence is the following: “I was led to the Lord by John Milton.” That was part of the written testimony of someone joining Tenth Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, and the author of it went on to explain that Paradise Lost was the work by Milton that was decisive in his conversion.

Is such a claim really possible? Yes: I have a small file of comparable testimonial statements about breakthrough spiritual experiences that my students attribute to reading and studying Paradise Lost. Several of them highlight the passage in Book 3 in which the Son offers to become human in order to redeem fallen humanity.

Poetry as a Means of Grace

Writing this article has provided the occasion for me to take stock of how Paradise Lost has been an important presence in my life for fifty-five years. Let me say immediately that my long-term contact with this book has been possible by virtue of my teaching it two or three times a year in my college literature courses. Would Paradise Lost have been such a continuous presence in my life if I did not teach it regularly? I do not know the answer to that question but thinking about the matter alerts me to how grateful I am to have been able to teach great literature as part of my working life.

As I turn now to the effect that this work has exerted in my life, I will note that the categories that I will name apply to most of the other literature that I teach as part of my vocation and that I read as a leisure time pursuit. The two overriding categories are edification and pleasure. We should not drive a wedge between the imaginative wonder of a literary masterwork and its spiritual impact. Share on X

As a framework for sharing my reflections on the major literary work of my life, I want to adduce a piece of advice offered in a 1941 book written by a Princeton University professor named Charles Osgood. The book bears the wonderful title Poetry as a Means of Grace, and it was written to encourage preachers to read imaginative literature. A piece of advice that the author offered in his introduction immediately struck me as an excellent idea. It was that even though we should cast our literary nets widely, there is much to be gained by adopting one author as our lifelong specialty, getting to know that author’s life and corpus as thoroughly as time allows. Among the advantages of claiming such expertise is that it makes one a member of a community of likeminded enthusiasts. Choosing a major author who has written a lot and about whom a lot has been written yields higher dividends than a less prominent author does.

One more “preliminary” that I want to place on the table is that what I say about the influence of Paradise Lost in my life is offered in the spirit that the principles I assert can be as true for another author and work as they are for John Milton and Paradise Lost.

Why Paradise Lost? Deliciousness.

If I could reconstruct why I chose this work as the subject of my dissertation and first book, I would have an answer, but that moment of decision is lost in the oblivion of the past. Doubtless Christian affinity played a crucial role. A former colleague once observed to me that many evangelical literary scholars find a way to explore their Christian interests incognito or by stealth operation, simply by their choice of subject. Examples include choosing a Christian author, or exploring the Bible as a literary influence on a given author, or placing a work into the Christian milieu in which it was produced.

What most immediately absorbed my analytic powers in regard to Paradise Lost, and what to this day I most obviously like about Paradise Lost, is the greatness of its literary form and technique. For sheer density of literary skill and effect, it is impossible to surpass Paradise Lost. It is a work that possesses what C. S. Lewis taught me to call line by line deliciousness.

Any great work is inexhaustible, but some works are more so than others. The quantity and diversity of literary criticism elicited by Paradise Lost means that there is always something new being discovered and offered to the public. The topics pursued at book length are staggering in themselves. That has been a huge part of the appeal to me in being not just a Miltonist but an expert on Paradise Lost specifically. There is so much to do with a masterwork like Paradise Lost.

I do not feel guilty in the least that there has been much to rivet me to Paradise Lost beyond its religious content. God is a God of beauty and artistry. We know that literary form matters to God because he gave us a literary Bible. My highest commendation of Paradise Lost is perfectly expressed in Samuel Johnson’s verdict regarding Milton that “whatever be his subject, he never fails to fill the imagination.”

We should not drive a wedge between the imaginative wonder of a literary masterwork and its spiritual impact. A literary critic said regarding Milton’s elegy Lycidas that “the beauty of the poem actually consoles, in a spiritual as well as aesthetic way,” and this exactly coincides with my own experience of the poem. In a similar vein, Francis Schaeffer claimed that “art may heighten the impact of the world view [expressed in a work of art], in fact we can count on this.”

So, too, in my life with Paradise Lost: the spiritual impact is tied up with the literary fullness that I have found. The same subject matter handled in a thinner artistic manner would not have won as strong an allegiance from me as Paradise Lost has.

Why Paradise Lost? Epic.

But Paradise Lost has also offered me a plenitude of spiritual nurture and encouragement in the faith. What form has it taken? Paradise Lost is an epic, and an epic is at some level what literary scholar Northrop Frye called “the story of all things.” This epic scope occurs on several levels. One is the level of human experiences portrayed, which a Christian author presents from a Christian perspective. It is a truism that the subject of literature is human experience, rendered concretely. Epic is the genre that covers more of human experience than other forms do. In an epic like Paradise Lost experience is embodied in the form of myth rather than everyday realism, so we need to translate the details of the remote mythical world into familiar forms. Once we have done that translation, we can see that a work like Paradise Lost “touches upon life powerfully at many points” (the famous touchstone for great literature offered by Victorian apologist for literature Matthew Arnold).

This superior scope exists at the level of ideas as well as human experience. In great literature, the ideas are fully incarnated in literary form, so the reading experience is not the same as perusing a systematic theology or reading a religious book. Nonetheless, the ideas enshrined in Paradise Lost are there for the taking if we apply our intellectual and theological powers. The whole vast fabric of Christian theology is laid out in Milton’s epic, and this has been a leading prompt for me to stay attuned to the great ideas of the Christian faith and apply them to my life. In great literature, the ideas are fully incarnated in literary form, so the reading experience is not the same as perusing a systematic theology or reading a religious book. Share on X

I have long told my students that virtually everything that Milton wrote can be read devotionally. The images that Milton places before us in Paradise Lost fall into the same categories as we find in the Bible—examples of moral and spiritual evil to avoid and images of good to emulate. The effect in my life has been devotional, redemptive, and often doxological, as I am led to praise God for the goodness of his ways, and to be thankful that I have been moved by the Christian influences in my life (including John Milton) to choose the narrow way that leads to life.

The Power of Forming, Sustaining, and Delighting

How has Paradise Lost been a presence in my life? It has fed my imagination, stimulated my intellect, and nurtured my soul. Milton’s masterwork has given me contact with greatness on multiple levels—imaginative, artistic, intellectual, and spiritual. Matthew Arnold claimed that great works of literature “will be found to have a power of forming, sustaining, and delighting us.” That is what Paradise Lost has done for me.