No Plato, No Augustine: The humility to quote their poets and philosophers

The latest issue of C redo Magazine focuses on Christian Platonism. The following is one of the issue’s featured columns by Matthew Barrett, executive editor of Credo Magazine.

redo Magazine focuses on Christian Platonism. The following is one of the issue’s featured columns by Matthew Barrett, executive editor of Credo Magazine.

Evangelical Christians today have a habit of objecting with great vehemence to anything “Greek”—Plato in particular—persuaded Christianity can only be corrupted by close acquaintance. As this common objection rattles through the air, irony oozes out like blood from a fresh gunshot wound. Future historians will one day have a great laugh in retrospect. For that same objection was behind Protestant Liberalism’s rejection of Christian orthodoxy. Adolf von Harnack said as much, convinced Nicene trinitarianism and Chalcedonian Christology are evidence that our fathers sullied Christianity with Greek concepts. Liberalism became Christianity’s savior, pushing aside classical metaphysics to redeem the true God and the real Jesus of the Gospels. As it turns out, Liberalism operated with a metaphysic of its own, one inherited from the fathers of modernity with their suspicion towards an unmoved mover, an eternal and immutable Creator who is a se, independent from a world otherwise entirely dependent on him. The ghost of Hegel hovered over their hermeneutic as they pretended they could interpret the scriptures without a metaphysic in place.

Biblical indeed

The objection to anything “Greek” by evangelical Christians is truly odd for another reason: evangelicals suspicious towards anything Greek express no little commitment to the scriptures and place no uncertain emphasis on its biblical background. The objection may reveal that we are not so familiar with the Bible as we think. For God’s providence is not random, nor is it blind; the Son of God was “made flesh” in the first century for a reason. The incarnation of Christ occurred within a Greco-Roman world, one that not only spoke and wrote in the Greek tongue but was encased within Greek concepts committed to notions like absolute truth, virtue, and reason. Hence the genius of Jesus’ beloved disciple John who opens his Gospel by calling Christ the Logos. Nor can we forget that the biblical authors themselves wrote their Gospels and Epistles in Greek, fully conscious that whenever truth is embodied within a language that same truth is communicated within its vocabulary, yes, but also within an entire conceptual paradigm.

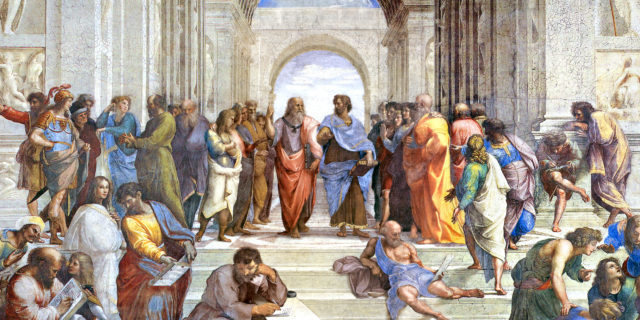

The apostle Paul—the missionary to the Gentiles—understood as much, which influenced his apologetic when he entered Athens and quoted their own poets and philosophers. In what had to be an awkward moment, Paul took the Athenians back to their own history to remind them that their own fathers believed we exist only by participating in the One who alone depends on no one for his own existence. What’s so telling about Acts 17 is this: Paul waits, holding off on introducing the gospel of Jesus Christ until the end, because he first must establish the type of God who creates and sustains the world. Yet to do so, Paul counters the Epicureans and Stoics by exposing the ways they have drifted from the Platonic tradition original to Athens, one that believed in a divinity who was the first cause, the unmoved mover, infinite and eternal, immutable and independent of the world.

Beyond false dichotomies

Examples are more numerous still, but by now the silliness of objecting to anything “Greek” should be apparent to anyone who reads the Bible within its original context. The real question, then, is not, “Greek or Christian?” That false dichotomy betrays not only divine providence, but truth as truth regardless of its cultural manifestation. A better question is this: in God’s providence what philosophy aligns most with his revelation of himself in the book of nature and can best serve his revelation of himself in the book of scripture? If general revelation means anything in the end, where exactly do we see its dividends?

From the church fathers to the Protestant Scholastics, the answer by pre-moderns was unanimous: Platonism. They were not naïve; they understood Platonism as Platonism alone contained grievous errors and was insufficient at best. Yet they also understood that pure Platonism’s grasp of reality was the superior philosophy by far. Over against other philosophies, Platonism drew on God’s general revelation most of all, from metaphysics to epistemology to ethics and eschatology. Platonism, however flawed in its explanation of the soul’s origin, for example, believed in transcendentals. Out of all philosophies, Platonism was fixated on God’s invisible attributes, his eternal power and divine nature as displayed in the world. Furthermore, Platonism was committed to a spiritual existence, persuaded that materialism cannot explain all that is real. We live and move and have our being in divinity because we are designed to ascend to divinity until we at last see God and find our greatest happiness in the beatific vision. To lose ourselves in the shadows when reality awaits us outside the cave is not merely unwise but ungodly; hence Plato developed an entire program for a just society based on the virtuous life and the happiness that awaits anyone who searches for God.Perceiving the philosophical truth within Platonism, the Great Tradition believed Platonism’s metaphysical commitments could serve Christianity. Click To Tweet

Take a page from Augustine

Perceiving the philosophical truth within Platonism, the Great Tradition believed Platonism’s metaphysical commitments could serve Christianity. Consider Augustine, for example, whose conversion to Christianity may have been an impossibility apart from Platonism. In his Confessions, Augustine explains why the Platonist books he read suddenly corrected his humanizing of divinity, giving him the metaphysical categories necessary to understand the transcendent God of Christianity, which he previously balked at whenever he encountered the scriptures. Augustine goes so far to say the Platonist books established the credibility of the Logos as well, so that when the young Augustine read about the Logos in John 1 he did not slip into a Christological heresy like Apollinarianism.

Thirteen years after Augustine wrote Confessions, he revisited the significance of Platonism for the Christian faith when he wrote The City of God. Augustine was a practitioner of natural theology based on Paul’s opening chapter to the Romans. God has manifested his invisible attributes in his creation, and he has granted those made in his image the cognitive faculties—e.g., reasonable observation—to perceive his eternal power and divine nature in the theater of his glory (Rom. 1:20). Therefore, Augustine is confident the book of nature can be the source for a natural theology, which motivates Augustine to discern who, among the philosophers, has most clearly perceived the Creator. Throughout his survey of ancient philosophy, Augustine puts forward a decisive answer: Platonism, out of all philosophies, contains a superior concept of the one God. In his own words, “there are philosophers who have conceived of God, the supreme and true God, as the author of all created things, the light of knowledge, the Final Good of all activity, and who have recognized him as being for us the origin of existence, the truth of doctrine and the blessedness of life. They may be called, most suitably, Platonists …we rank such thinkers above all others and acknowledge them as representing the closest approximation to our Christian position.” In short, “There are none who come nearer to us than the Platonists.”

The reasons for Platonism’s superiority to other philosophies are summarized by Augustine’s list of defining marks. The Platonists conceive of God as:

- the supreme and true deity

- the author of all created things (origin of existence)

- the light of knowledge

- the Final Good of all activity

- the truth of all doctrine

- the blessedness of life

Augustine's conversion to Christianity may have been an impossibility apart from Platonism. Click To TweetAugustine disqualifies other philosophies besides Platonism because they look for an explanation of the cosmos in the cosmos itself, that is, among life which is mutable and composite. From Epicureanism to Stoicism, they maintain that “the cause and origin of the universe is to be found in material bodies, simple or compound, inanimate or animate, but still material bodies.” The Platonists shine in contrast because they understand that only an immutable, immaterial, and supreme being can be the explanation of all change in this world. The Platonists “have been raised above the rest by a glorious reputation they so thoroughly deserve” because “they recognized that no material object can be God.” Passing by all material deities in the religions surrounding them, the Platonists “raised their eyes above all material objects in their search for God.” They comprehended that an immutable deity was a superior deity.

“They realized that nothing changeable can be the supreme God; and therefore in their search for the supreme God, they raised their eyes above all mutable souls and spirits. They saw also that in every mutable being the form which determines its being, its mode of being and its nature, can only come from him who truly is, because he exists immutably.”

To explain a material and mutable universe, they contended, requires a being “who simply is.” The Platonists, in other words, not only established the necessity of immutability but simplicity for divinity. “For him existence is not something different from life, as if he could exist without living; nor is life something other than intelligence, as if he could live without understanding; nor understanding something other than happiness, as if he could understand without being happy. For him, to exist is the same as to live, to understand, to be happy.”

If deity is immaterial, immutable, and simple, so must God be a se to explain a world derived and dependent. “It is because of this immutability and this simplicity that the Platonists realized that God is the creator from whom all other beings derive, while he is himself uncreated and underivative.” To use the language of the Platonists, “both body and mind might be more or less endowed with form (or ‘idea’), and if they could be deprived of form altogether they would be utterly non-existent. And so they saw that there must be some being in which the original form resides, unchangeable, and therefore incomparable. And they rightly believed that it is there that the origin of all things is to be found, in the uncreated, which is the source of all creation.”

In view of these Platonic principles, Augustine draws a decisive conclusion that sets the trajectory of the entire Western project on which medieval and reformed metaphysics has depended ever since: “This is why we rate the Platonists above the rest of the philosophers. The others have employed their talents and concentrated their interests on the investigation of the causes of things, of the method of acquiring knowledge, and the rules of the moral life, while the Platonists, coming to a knowledge of God, have found the cause of the organized universe, the light by which truth is perceived, and the spring which offers the drink of felicity.”

Augustine knew that Platonism on its own, left to itself, was insufficient. Platonism provided Augustine with sight of the homeland from the mountaintop, but the gospel of Jesus Christ then followed as his guide, his illuminating light, showing Augustine the path to reach that happy land of the beatific vision itself.