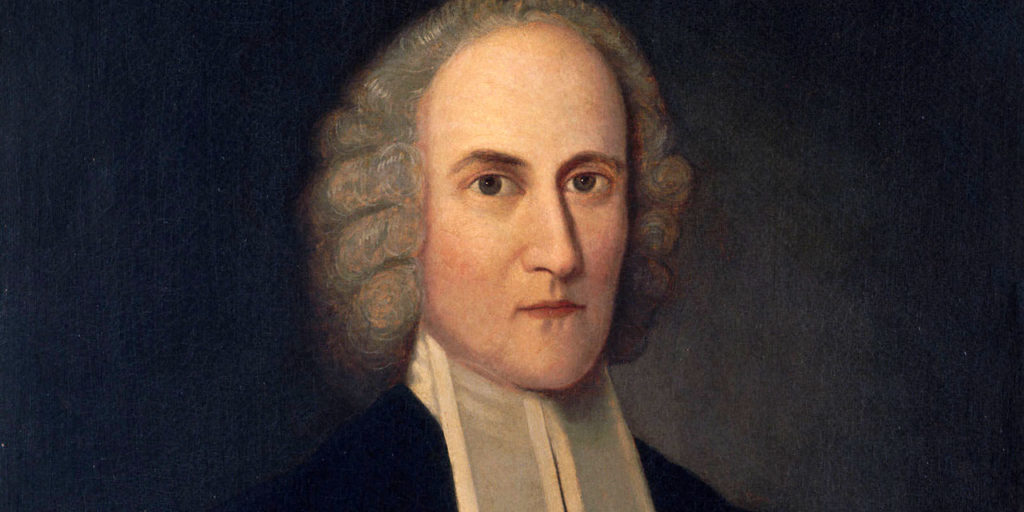

What is saving faith really? Jonathan Edwards’ departure from Reformed theology, Part 2

Historian of American history, Gary Steward, once again turns – ad fontes – to the writings of Jonathan Edwards in this second article. In Part 1 Steward argued that Edwards broke with the Reformed tradition over sola fide by moving beyond notitia, assensus, and fiducia to inject into justifying faith other virtues like love. In Part 2, Steward now turns to the many instances in Edwards’s writings where obedience and perseverance are incorporated into justification as well, much in contrast to others like Calvin and Turretin.

The Role of Obedience in Justification

Edwards’s variance with his tradition on the issue of sola fide is seen even more clearly when we face the role of obedience in justification. In Part 1 of this series, I quoted Miscellany #218, entitled “Faith, Justifying,” where Edwards states the following:

‘Tis the same agreeing or consenting disposition that according to the divers [sic] objects, different states or manner of exertion, is called by different names. When ‘tis exerted towards a Savior, [it is called] faith or trust…when toward unseen good things promised, faith and also hope; when towards a gospel or good news, faith; when towards persons excellent, love; when towards commands, obedience; when towards God with respect to changes, ‘tis properly called resignation; when with respect to calamities, submission.

Edwards sees no difficulty blurring the distinction between faith and obedience. The Reformed tradition, on the other hand, held that faith alone, apart from obedience, apprehends Christ for justification in him. While faith alone justifies, faith is “not alone in the person justified, but is ever accompanied with all other saving graces.”[1] Turretin states the Reformed position in this way:

The question is not whether solitary faith (i.e., separated from the other virtues) justifies (which we grant could not easily be the case, since it is not even true and living faith); but whether it ‘alone’ (sola) concurs to the act of justification (which we assert)… The coexistence of love in him who is justified is not denied; but its coefficiency or cooperation in justification is denied… The question is not whether the faith ‘which justifies’ (quae justificat) works by love (for otherwise it would not be living but dead); rather the question is whether faith ‘by which it justifies’ (qua justificat) or in the act itself of justification, is to be considered under such a relation (schesei) (which we deny).[2]

For every part of evangelical obedience is an implicit reception of Christ and an act of justifying faith. -Edwards Click To Tweet Although faith “works by love” and is accompanied by other saving graces, these acts are of no consideration in faith’s power to effect justification. Turretin goes on to state:

“It is one thing for love and works to be required in the person who is justified (which we grant); another [to be required] in the act itself or causality of justification (which we deny). If works are required as concomitants of faith, they are not on that account determined to be causes of justification with faith or to do the very thing which faith does in this matter.”[3]

Turretin continues: “…our works of whatever kind cannot merit life, nor have they the relation of an instrument for apprehending it.”[4] Calvin similarly defends sola fide and states that just as ceremonial works are excluded from that which brings about justification, “moral works are also excluded from the power of justifying.”[5] Faith alone in the Reformed tradition “causes” justification; that is, faith alone is the sole “instrument” by which Christ and his purchased benefits are received.

For Edwards, evangelical obedience (obedience which is done in connection with gospel faith) is not excluded from the “natural fitness” which forms the foundation of our legal union with Christ. While the Reformed tradition was careful to exclude Christian obedience from what connects us to Christ, Edwards’s only concern is to exclude the merit or “moral fitness” of obedience from consideration. Once “moral fitness” is categorically excluded, Edwards sees no problem joining faith and obedience together in what makes it “naturally fitting” that we should be looked upon by God the Judge as one with Christ. So long as God is not conceived of as granting union with Christ as a “reward” for faith and obedience, Edwards is comfortable making obedience part of the soul’s justifying reception of Christ. Edwards is comfortable making obedience part of the soul’s justifying reception of Christ. Click To Tweet

This was the trajectory forged out by Edwards in his Master’s thesis on justification. Edwards states:

When it is asserted that a sinner is justified by this faith alone, we mean, of course, that God receives the sinner into his grace and friendship for this reason alone, that his entire soul receives Christ in such a way that righteousness and eternal life are offered in an absolutely gratuitous fashion and are provided only because of his reception of Christ. We are not even asking whether or not we are justified by this evangelical obedience, but whether we are justified by this evangelical obedience because of its intrinsic goodness, or merely because it is only by evangelical obedience that Christ is received. For every part of evangelical obedience is an implicit reception of Christ and an act of justifying faith.[6]

Edwards is very clear: every part of evangelical obedience is an implicit reception of Christ and an act of justifying faith.

Once the gracious nature of justification is established, Edwards has no difficulty fusing “evangelical obedience” with faith in the soul’s justifying reception of Christ. This position is repeated even more clearly in Edwards’s Justification by Faith Alone:

Faith unites to Christ, and so gives a congruity to justification, not merely as remaining a dormant principle in the heart, but as being, and appearing in its active expressions. The obedience of a Christian, so far as it is truly evangelical, and performed with the spirit of the Son sent forth into the heart, has all relation to Christ the Mediator, and is but an expression of the soul’s believing unition to Christ: all evangelical works are works of that faith that worketh by love; and every such act of obedience, wherein it is inward, and the act of the soul, is only a new effective act of reception of Christ… So that as was before said of faith, so may it be said of a child-like, believing obedience, it has no concern in justification by any virtue, or excellency in it; but only as there is a reception of Christ in it.[7]

So faith, for Edwards, unites to Christ as it exists in “active expressions” of evangelical obedience. As “every such act of obedience” contains “a reception of Christ in it,” it is not to be excluded from that which unites us to Christ and effects justification. Edwards says elsewhere, “…the acts of the Christian life can’t be concerned in this affair [i.e. justification] any otherwise, than as they imply, and are the expressions of faith, and may be looked upon as so many acts of reception of Christ the Savior.”[8]

In handling the apparent contradiction between James and Paul on justification by faith alone, Edwards argues that Paul and James are using the word “justify” differently—a common position common in the Reformed tradition.[9] Realizing that this answer might not satisfy everyone, Edwards reiterates his stated position on faith and obedience once again:

If notwithstanding, any choose to take justification in St. James’s, precisely as we do in Paul’s epistles, for God’s acceptance or approbation itself, and not any expression of that approbation, what has been already said concerning the manner in which acts of evangelical obedience are concerned in the affair of our justification, affords a very easy, clear, and full answer: for if we take works as acts or expressions of faith, they are not excluded; so a man is not justified by faith only, but also by works; i.e. he is not justified only be faith as a principle in the heart, or in its first and more immanent acts, but also by the effective acts of it in life, which are the expressions of the life of faith.[10]

With this statement, one can see how clearly Edwards’s position differs from the Reformed position of sola fide. God’s acceptance and approbation of a sinner in justification is accomplished not only by faith “in the heart” but also by the fruits of faith done throughout the whole life of a believer (i.e. “works”).

Defenders of Edwards on this regard have failed to give due consideration to how Edwards blends faith and obedience together to form the soul’s composite action of justifying unition with Christ. Click To Tweet Defenders of Edwards on this regard have failed to give due consideration to how Edwards blends faith and obedience together to form the soul’s composite action of justifying union with Christ. Samuel Logan, for example, defends Edwards by trying to make obedience in Edwards only a sine qua non of justification. Says Logan: “…Edwards proclaims that there are other conditions as well [besides faith]. …Justification is conditioned upon obedience in the sense that with genuine evangelical obedience justification shall be and without genuine evangelical obedience justification shall not be. Thus, justification and sanctification are inseparable…”[11] While Logan’s assessment of Edwards is true as far as it goes, Edwards’s statements on the place of obedience in justification go far beyond what Logan expresses. For Edwards, justification depends upon evangelical obedience, even as if it were the very meritorious ground of justification. Edwards states his position in this very way:

The Scripture doctrine of justification by faith alone…does in no wise diminish, either the necessity, or benefit of a sincere evangelical universal obedience: in that man’s salvation is not only indissolubly connected with it, and damnation with the want of it, in those that have opportunity for it, but that it depends upon it in many respects; …even in accepting of us as entitled to life in our justification, God has respect to this, as that on which the fitness of such an act of justification depends: so that our salvation does truly depend upon it, as if we were justified for the moral excellency of it.[12]

Edwards states that justification depends upon evangelical obedience. Click To Tweet For Edwards, there is not only an indissoluble connection between evangelical obedience and justification; rather, Edwards goes far beyond Logan and states that justification depends upon evangelical obedience. It does so because it unites to Christ and forms a part of the non-meritorious foundation of the “fitness” by which we are viewed as in Christ. George Hunsinger has stated in this regard: “Edwards here crosses a fine line laid down by the Reformation. He moves from affirming that faith is not without works to the very different insistence that works, as the external expression of faith, play a role in justification… Works [in Edwards] are not just external evidences that faith exists. They are necessary to the efficacy of faith.”[13] This is a significant divergence from the Reformation, then, regarding sola fide.

The Role of Perseverance in Justification

In arguing for sola fide, the Reformed tradition reasoned that all works of obedience must be excluded from both the ground and instrument of justification, for such obedience only begins to be viewed by God as good and praiseworthy once a believer is in a justified state.[14] The Reformed tradition also argued that good works performed after justification (evangelical obedience) must also be excluded for, as Calvin says, “…it is absurd that an effect precedes its cause.”[15] Justification takes place at a single point in time; works of evangelical obedience and perseverance follow as consequent. Justification in the tradition of the Reformation (properly speaking) is not a repeatable event but a transferal of status in the eyes of God.

Our salvation does truly depend upon it (obedience), as if we were justified for the moral excellency of it. -Edwards Click To Tweet Turretin represents the Reformed tradition in viewing justification as a once-for-all transferal of an individual out of a state of condemnation into a state of acceptance when he says: “…justification take[s] place in this life in the moment of effectual calling, by which the sinner is transferred from a state of sin to a state of grace and is united to Christ, his head, by faith. For hence it is that the righteousness of Christ is imputed to him by God, by whose merit apprehended by faith he is absolved from his sins and obtains a right to life.”[16] Future acts of perseverance flow out of this newly obtained status and are not viewed as conditions of it.

Once again, Edwards deviates from the Reformed traditional significantly in this regard. For Edwards, justification does not depend only upon the first instance of genuine faith. Continual perseverance in faith and obedience is necessary in order to provide a perpetual “fitness” for God to keep viewing an individual as one with Christ. Justification, for Edwards, continually depends upon the qualification of faith and obedience being continually present in the life of the believer. As Edwards says,

Justification is by the first act of faith, in some respects, in a peculiar manner, because a sinner is actually and finally justified as soon as he has performed one act of faith; and faith in its first act does, virtually at least, depend upon God for perseverance, and entitles to this among other benefits. But yet the perseverance of faith is not excluded in this affair; it is not only certainly connected with justification, but it is not be excluded from that on which the justification of a sinner has dependence, or that by which he is justified.[17]

Edwards crosses a fine line laid down by the Reformation. Works are not just external evidences that faith exists. They are necessary to the efficacy of faith. -George Hunsinger Click To Tweet For Edwards, legal union with Christ and justification are continually dependent upon the “natural fitness” of the soul’s real unition with Christ. Therefore, each moment’s real union with Christ forms the basis for each moment of justification. Future acts of faith, for Edwards, have the same function in justification as the first act of faith. He continues: “And there is the same reason why faith, the uniting qualification, should remain, in order to the union’s remaining, as why it should once be, in order to the union’s once being.”[18] Each moment of a sinner’s justification depends, then, upon each moment of faith: “Perseverance of faith is necessary, even to the congruity of justification… Perseverance in faith is thus necessary to salvation, not merely as a sine qua non, or as an universal concomitant of it, but by reason of such an influence and dependence.”[19] Edwards distinguishes his position from the Roman Catholic position by saying that a believer possesses complete justification upon the first act of faith:

Although the sinner is actually, and finally justified on the first act of faith, yet the perseverance of faith, even then, comes into consideration, as one thing on which the fitness of acceptance to life depends. God in the act of justification…has respect to perseverance, as being virtually contained in that first act of faith… God has respect to the believer’s continuance in faith…as though it already were, because by divine establishment it shall follow.[20]

Because God views perseverance as a property of genuine faith, he can consider the condition of future instances of faith as virtually accomplished. For this reason, he continues, “justification is not suspended; but were it not for this it would be needful that it should be suspended, till the sinner had actually persevered in faith.”

Whereas the first instance of genuine faith was uniquely significant for Calvin and Turretin in effecting a transferal of status, Edwards sees the significance as only incidental: “…all the difference whereby the first act of faith has a concern in this affair that is peculiar, seems to be as it were only an accidental difference, arising from the circumstance of time, or its being first in order of time; and not from any peculiar respect that God has to it, or any influence it has of a peculiar nature, in the affair of our salvation.”[21] Edwards significantly downplays the abiding status that is gained in the first act of justifying faith, making a believer’s future acts of faith, just as significant and consequential as an unbeliever’s first act of saving faith.

By making a believer’s future acts of faith and obedience conditions of justification, Edwards has radically altered the place of obedience within the Christian life. Whereas in the Reformed tradition, future acts of faith and evangelical obedience were to follow justification necessarily as the fruit and evidence of a believer’s spiritual state and legal standing before God, Edwards says that believers are to persevere in faith and obedience in order to be justified. Christians, in other words, are to continually seek after justification by trusting and obeying. Edwards makes this point when he reasons: “If no other act of faith could be concerned in justification but the first act, it will then follow that Christians ought never to seek justification by any other act of faith. For if justification is not to be obtained by after-acts of faith, then surely it is not a duty to seek it by such acts…”[22]

But on the contrary, Edwards thinks it is the duty of Christians to seek justification by the “after-acts of faith.” Arguing from multiple passages of Scripture, Edwards thinks it is clear that justified believers are to keep seeking after justification. David’s repentance in Psalm 32, Paul’s pursuit of righteousness in Philippians 3:8-11, Abraham’s justification in Genesis 15:6 instead of Genesis 12, and the petition in the Lord’s prayer to “forgive us our sins” are all used by Edwards to show how a believer is to continually seek after justification through faith, repentance, obedience, and prayer.[23] Given the breadth of activity Edwards subsumes under “the after-acts of faith,” sola fide once again seems significantly compromised.

To summarize this point, Edwards steps away from the Reformed tradition once again by downplaying the significance of the change in status that occurs on the first act of faith and by holding that the “after-acts of faith are concerned in the business of justification” and “it is proper…to seek after justification by such acts.”[24] One can only speculate if more is going on in Edwards’s mind behind the scenes the meets the eye. Perhaps it is Edwards’s understanding of the continuous, moment-by-moment re-creation of the soul ex nihilo that caused him to downplay the once-for-all conferral of a justified status to the sincere believer as the foundation for the Christian’s perseverance.[25] This might help explain Edwards’s desire to posit the need for a continuously-laid foundation for justification in the soul for each successive moment of life.

Why did Edwards fold the whole of the Christian life into justifying faith?

I have suggested that while the main outlines of Edwards’s writing on justification by faith alone support the Reformed notion of sola fide, particular details in Edwards’s understanding undermine many of the key distinctions that defined sola fide for the Reformed tradition, including the essence of faith, the relationship between faith and love, the relationship of faith and obedience, and the role of perseverance in justification. Edwards compromises the key Reformation distinctive of sola fide by blending faith and its fruits and by making the justifying effect of faith depend upon faith’s fruits and continuance. Where the Reformed tradition labored to distinguish between faith and the fruits of faith, Edwards’s key distinction is instead between faith and its fruits as providing a “natural fitness” for union with Christ and faith and its fruits as providing merit for the “reward” of Christ’s righteousness. When he critiques the Arminian notion that righteousness can be merited, Edwards is in-line with his tradition, but when he folds effectively the whole of the Christian life into justifying faith, he steps away from the Reformed tradition significantly, and sola fide is virtually destroyed. When Edwards folds effectively the whole of the Christian life into justifying faith, he steps away from the Reformed tradition significantly, and sola fide is virtually destroyed. Click To Tweet

What motivated Edwards to depart from the Reformed tradition in this regard? Edwards seems compelled to step away from sola fide because of the threat posed by Antinomianism. Edwards did not think it sufficient to make evangelical obedience and perseverance only the necessary fruits and evidences of justifying faith or a sine qua non of justification as the Reformed tradition had done. Instead, for Edwards, justification must “truly depend upon it, as if we were justified for the moral excellency of it.”[26] All acts of faith, love, repentance, and obedience in the Christian’s life form an individual’s real union with Christ, and on that basis establish a natural fitness for being viewed as one with Christ before the bar of God’s justice. As we have seen, this significantly changes the role of obedience in the Christian life. For Edwards, Christians are to obey, love, repent, and persevere in order to be justified in continuance. This seems to be exactly what the Reformed notion of sola fide was intended to avoid. As Turretin says: “It is one thing for the love of the sinner to be the cause of the remission of sins a priori; another to be the effect and proof a posteriori.[27]

While conventional wisdom has viewed Edwards as occupying a place squarely in the Reformed tradition, other scholars have rightly critiqued Edwards on these same points as well. Thomas Schafer noted in 1951, “the reader cannot help feeling that the conception of ‘faith alone’ has been considerably enlarged—and hence practically eliminated. …one may fairly ask whether Edwards has retained a unique act of the soul called faith which becomes the condition of justification separately from all other acts of the soul.”[28]

Robert Godfrey more recently echoed this analysis when he stated: “The unique character of faith is further distorted by the elements that Edwards seemed to see as definitive of or inherent in of [sic] faith. He repeatedly stated that various elements—including repentance, obedience, and perseverance—were either ‘virtually’ present in faith or were to be identified with faith.”[29]

Defenders of Edwards in this regard have wrongly read Edwards as if he were saying nothing more than that “evangelical obedience is an absolute necessity”[30] or a sine qua non of justification. Edwards says something much different than this. Although Edwards held to the imputation of Christ’s righteousness as the sole formal basis for our justification, and although he sought to exclude all personal merit from justification, the Reformed understanding of sola fide is so re-worked in Edwards that it becomes virtually unrecognizable.[31] Though adopting the Reformation slogan and using it in his macro-structure, the details of Edwards’s position at this particular point significantly undermine the Reformed position he sought to defend.

Old Princeton proved much less innovative and much more successful in defending Protestant orthodoxy than the innovative tradition of Edwards. Click To Tweet Edwards’s innovations in this and other areas of his thought (e.g., continuous creation) introduced great instability in the school of thought his followers developed and that dominated New England in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. While often panned as being corrupted by Enlightenment rationalism, the theological tradition that developed at Old Princeton proved much less innovative and much more successful in defending Protestant orthodoxy than the innovative tradition of Edwards.

In tomorrow’s post, I will recommend treatments of justification in the Reformed tradition that proved more consistent than Edwards.

*An academic version of these articles was presented in 2017 at ETS.

Endnotes

[1]Westminster Confession of Faith, XI.2.

[2] Turretin, 2:677.

[3] Turretin, 2:680.

[4] Turretin, 2:681.

[5] Calvin, 1:749.

[6] WJE, 14:61 (emphasis mine).

[7] WJE, 19:207 (emphasis mine).

[8] WJE, 19:201.

[9] WJE, 19:230-236.

[10] WJE, 19:236 (emphasis mine).

[11] Logan, 41.

[12] WJE, 19:236 (emphasis mine).

[13] Hunsinger, 117.

[14] Calvin, 1:770, 775-776.

[15] Calvin, 1:816.

[16] Turretin, 2:684.

[17] WJE, 19:201-202 (emphasis mine).

[18] WJE, 19:202-203.

[19] WJE, 19:206.

[20] WJE, 19:203.

[21] WJE, 19:207.

[22] WJE, 19:204.

[23] WJE, 19:203-206.

[24] WJE, 19:204-205. Edwards makes his disagreement with the Reformed tradition explicit when he states in Miscellany #729: “Though perseverance is acknowledged by Calvinian divines to be necessary to salvation, yet it seems to me that the manner in which it is necessary has not been sufficiently set forth. ’Tis owned to be necessary as a sine qua non… But we are really saved by perseverance, so that salvation has a dependence on perseverance… …not only the first act of faith, but after-acts of faith, and perseverance in faith, do justify the sinner…” (The Works of Jonathan Edwards: Vol. 18, The “Miscellanies,” 501-832 [ed. Ava Chamberlain; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000], 353-355).

[25] See Jonathan Edwards, The Works of Jonathan Edwards, Volume 3: Original Sin (ed. Clyde A. Holbrook; New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970), 398-401.

[26] WJE, 19:236. See also Godfrey, 39-40.

[27] Turretin, 2:680.

[28] Schafer, 59-60.

[29] Godfrey, 37.

[30] Logan, 43. See also Logan, 41.

[31]“While Edwards thought of himself as a faithful teacher of the [Reformed] tradition, he was not afraid to revise and develop it” (Michael J. McClymond and Gerald R. McDermott, The Theology of Jonathan Edwards [New York: Oxford University Press, 2011], 667).