The nature, role, means, possibility, purpose, renderings, and use of Natural Theology have been discussed by Christian theologians and philosophers, since, at very least, Augustine and his The City of God.[1] For Augustine, Natural Theology was that knowledge—those truths—about God which the philosophers, such as Plato, had obtained through reasoned observations of the sensible cosmos.[2] This became the traditional understanding of Natural Theology.

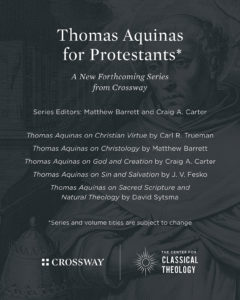

Thomas Aquinas, without using the term “Natural Theology,” discusses this natural knowledge of God in many of his works, including the Summa Theologiae, Summa Contra Gentiles, his Commentary on Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, his commentary on Boethius’s De Trinitate, and so on. If discussing Aquinas’s approach to Natural Theology was as simple as explaining what he says about it in these works, it could be done in a single paper. It is not so simple, if only because, from the time of Aquinas to the present moment, there has been an ongoing discussion between friends and enemies of Aquinas as to just what Aquinas actually thinks about this natural knowledge of God, and whether he is right. In the last 150 years alone, there has been such a great wealth of material published on the subject, that even Thomas Joseph White’s excellent contribution to the Thomistic doctrine of Natural Theology[3]—in which he not only interacts with important nay-sayers such as Heidegger, Kierkegaard, and Barth, but also interacts with 3 different Thomistic articulations of Aquinas (namely Maritain, Rahner, and Gilson)—does not quite say all that needs to be said.

My goal, in what follows, is to provide a clear introductory articulation of Aquinas’s understanding of Natural Theology, in conversation with some contemporary interpreters of Aquinas.

The Preambles, Theology, and Christian Belief

I n his commentary on Boethius’ De Trinitate, Aquinas say that philosophy can be used in Sacred theology in three ways. The first of those ways is “in order to demonstrate the preambles of faith, which we must necessarily know in [the act of] faith. Such are the truths about God that are proved by natural reason, for example, that God exists, that he is one, and other truths of this sort about God or creatures proved in philosophy and presupposed by faith.”[4]

n his commentary on Boethius’ De Trinitate, Aquinas say that philosophy can be used in Sacred theology in three ways. The first of those ways is “in order to demonstrate the preambles of faith, which we must necessarily know in [the act of] faith. Such are the truths about God that are proved by natural reason, for example, that God exists, that he is one, and other truths of this sort about God or creatures proved in philosophy and presupposed by faith.”[4]

In chapter 3 of the Summa Contra Gentiles, Aquinas says, “Some truths about God exceed all the ability of the human reason. Such is the truth that God is triune. But there are some truths which the natural reason also is able to reach. Such are that God exists, that He is one, and the like. In fact, such truths about God have been proved demonstratively by the philosophers, guided by the light of the natural reason.”[5]

For Thomas, there are a certain number of truths which can be known via natural reason, and which are implicit in the act of faith.[6] In the above quotes, he gives a non-comprehensive list of some of those truth claims which have traditionally fallen under the domain of Natural Theology. For Thomas, note, Natural Theology is a knowledge that man can have, through “natural” or philosophical means,[7] of the divine nature, without appeal to special revelation. These preambles are properly proved, for Aquinas, in philosophy, and are accepted as true by the theologian.

It is important to note that, for Aquinas, actual “knowledge” of the preambles is not necessary for salvation, and knowledge of the preambles is not sufficient for salvation. On the contrary, as he clearly explains in the Summa Theologiae I, q. 1, a. 1,[8] special revelation in Christian Scriptures was necessary for three reasons.[9] First of all, this natural, philosophical, knowledge of God was obtained only by a small (“a paucis”) amount of people.[10] He is not, here, talking about that vague, pre-philosophical, and very general knowledge of God which is in all men,[11] but demonstrative knowledge that God is. This philosophical knowledge is, in principle, obtainable by all men (as all men are rational beings), but, as so few actually attain it, says Thomas, it was necessary that God reveal himself through Holy Writ.

Secondly, that philosophical knowledge of God which Aquinas includes as a preamble of faith also took a long time (per longum tempus) to obtain. Aquinas is saying nothing more complicated here than that, historically speaking, it took humanity quite a while to arrive at clear demonstrations which prove that God is.[12]

Thirdly, even that which was known by the philosophers[13] was a mixture of truth and error (admixtione multorum errorum).[14] The philosophers, despite their brilliance, only arrived at the knowledge they had acquired about God after a long time, and what they did know was intermingled with many erroneous opinions about God.[15]

The necessity of Christian Scriptures, for the salvation of man, reveals that Aquinas does not in any way think that most Christians need to “know” the truths of the preambles in order to be Christian.[16] Rather, the preambles may be as much an object of belief for many people as any truths which is revealed in Christian scriptures and encoded in the Apostle’s Creed. It is as rational and intellectually virtuous for humans to accept the truth of the preambles on the basis of the trustworthiness of a recognized authority,[17] as it is for humans to seek to understand and demonstrate the preambles.For Aquinas, it is impossible for Natural Theology to lead to a salvific knowledge of God. Share on X

However, we must not therefore forget that, for Aquinas, each of the preambles is demonstrated in philosophy, and, therefore, can be known as true. Truths arrived at through philosophical means, such as “God is,” “God is good, perfect, immutable, impassible, eternal, and so on,” cannot contradict the scriptures, properly interpreted; and serve Sacred Theology as keys to the proper interpretation of the scriptures.[18] Though the Christian layman is in no way obligated to know the preambles prior to belief, it is incumbent on the Christian theologian to study that which philosophy teaches us truly about God.

Demonstrating that God Is

Thomas clearly includes amongst the preambles of faith—those truths which are known by human reason without appeal to Christian scriptures, and which are properly studied by philosophers—the truth that “God is”.[19] In the Summa Theologiae I, question 2, articles 1 and 2, Aquinas asks whether the proposition “God is” is self-evident (a. 1) and whether the proposition “God is” is demonstrable (a. 2).[20] To the first question, Thomas says, “yes and no”. To the second, he gives a resounding “yes”. To understand his answers, we need to dive into the important distinctions that he makes.

Is “God is” Self-Evident?

In relation to this first question (q. 2, a. 1), Thomas explains that there are two ways in which a proposition can be said to be self-evident: (1) in itself and to the human intellect, and (2) in itself, but not to the human intellect. A predicative proposition (such as “S is P”) is self-evident when the predicate (praedicatum) is included in (is properly included in, or is essential to) the definition or concept (ratione) of the subject (subjecti). For example, the predicative statement, “Man is animal (homo est animal)” is self-evident, because the predicate “animal” is properly included in the definition of “man.” This statement is an example of a predicative statement which is self-evident in the first way.

A predicative statement is self-evident in the second way when the nature or essential definition/concept of the subject is not knowable by human beings. For the predicative statement “God is” to be self-evident in the first way, man would have to have knowledge of (at least be able to “know”) the divine nature. For Aquinas, and, in fact, for the entire tradition of Christian thought preceding Aquinas, man cannot know the divine nature in itself.[21] It follows that the predicative proposition “God is” is not self-evident in the first way.[22]

It is, however, self-evident in the second way.[23] That is, God, by nature, is. As such, the predicate “is” is necessarily included in the subject of the predicative statement, “God.” Therefore, though it is not self-evident to the human intellect, the predicative statement “God is” is self-evident in itself.

Is “God is” Demonstrable?

How, then, would we know the truth of the predicative statement “God is”? Thomas clearly thinks, as we have already shown, that we can know the truth of this predicative statement, and that it is the proper role of philosophy to demonstrate it. This is what will be addressed in the second question (q. 2, a. 2), where Aquinas clearly says that the predicative statement “God is” is demonstrated philosophically.

Note, Aquinas is not asking whether arguments can be given which would make it reasonable to believe that God is, nor whether arguments can be given which would make it more probable than not that God is.[24] Aquinas clearly thinks that there are at least 5 formally valid and sound proofs which demonstrate that God is (q. 2, a. 3). These are known as the 5 Ways. Aquinas provides the apostle Paul as the authority for the truth that “God is” is demonstrable, quoting Romans 1:20, which has been traditionally understood as teaching that something of God (that God is, and something of the divine nature) is known by our reasoned observations of the sensible cosmos. Aquinas notes that this verse would be false if it was impossible to demonstrate that God is. God does not lie, and his word is always true; therefore, it is possible to demonstrate the truth of the statement, “God is.” Aquinas clearly thinks that there are at least 5 formally valid and sound proofs which demonstrate that God is. Share on X

Aquinas goes on to distinguish between 2 types of demonstration:

(1) Demonstratio propter quid

(2) Demonstratio quia.[25]

In the first type of demonstration, we begin with the nature of something and then demonstrate some other truth which is proper to that thing.[26] In the second type of demonstration we begin with some observed effect, and infer the necessary existence, and something of the nature, of its cause.

This second type of demonstration begins with what is first to us in the intellect, even if it is last in relation to its principle. That is, in this form of reasoning, we arrive at knowledge of the cause only after and through knowledge of the effect. Hearing the sound of glass breaking (effect), we infer that something made of glass has broken (cause of the effect). Upon going to the kitchen and seeing a broken glass on the floor (effect), we infer that something has caused the glass to fall to the ground and break (cause).[27] This second type of demonstration is basically an application of the principle of causality,[28] and is the only method of demonstration which can be used to demonstrate the truth of the statement “God is.”[29]

One of the criticisms which has sometimes been leveled against the possibility of such demonstrations, is that one must presuppose or assume a prior definition of God. This is not a recent critique, and, in fact, was discussed by Aquinas in the contrary opinions of the article in question. He notes, in the second contrary opinion of question 2, article 2, that, “the middle term of a demonstration is that which the subject is; but, we cannot know, of God, that which He is, only what he is not, as Damascene says. Therefore, we cannot demonstrate that God is.”[30] In other words, we cannot demonstrate that God is without prior knowledge of what God is. Therefore, any attempt to demonstrate that God is presupposes knowledge of what God is.

In response to this contrary opinion, Aquinas notes that in Demonstratio Quia it is not necessary to have any knowledge of the nature of the subject. All that is needed is a nominal definition of the middle term.[31] This could be thought of as a temporary place holder for whatever is the “cause” of the effects from which the demonstration begins.

That God Is

Aquinas, in his various works, provides us with a number of demonstrations which he thinks provide us with knowledge of the truth that “God is”.[32] For Aquinas, if you understand the demonstrations (both that the premises are true and how they are related), then you know that God is. The most well-known demonstrations are found in ST I, q. 2, a. 3, where he argues, via Demonstratio Quia, from five observable effects to the existence of God.

In the first way, which Aquinas thinks is the most obvious, he demonstrates that there is necessarily a first unmoved mover from the fact, evident to the senses, that something changes.

In the second way, he demonstrates that this first unmoved mover is the first efficient cause from the observation of orders of efficient causes. Based on the 5 ways alone, we know not only the truth that “God is,” we also know that God is the sovereign, immutable, necessary, intelligent, provident, and final and efficient cause (creator) of all things. Share on X

In the third way, he demonstrates that this first unmoved mover “is” necessarily in itself, from the observation of beings which are both contingent and necessary (but not of themselves).

In the fourth way, he demonstrates that this first unmoved mover is the highest, greatest, or sovereign (“maxime”) Good, True, Noble, and Being,[33] from the observation of degrees of goodness, truth, nobility, and so on, in the sensible world.[34]

In the fifth way, which is today wrongly confused with the intelligent design argument, Aquinas demonstrates that this unmoved mover is the intelligent and provident creator, from the observation of a natural teleology (end-directedness) in the things of the sensible cosmos.

Demonstrating What God is (not)

We can demonstrate, and therefore know through the natural light of reason, that God is; but Aquinas also thinks that we can know, in this way, something of the divine nature—specifically, what it is not. However, as some Thomists have noted, this does not mean that we cannot come to some “positive” knowledge of the divine nature. John Wippel, for example, notes that “in the course of denying any kind of quiddative knowledge to us in this life, and while still following the way of negation, Thomas goes on to refer to God as all perfect…By denying any kind of imperfection of God, he now draws the conclusion that God is all perfect.”[35] It is important to remember that when Aquinas arrives at what might be called positive predication of the divine nature, he clearly thinks that this is only done via analogical predication.[36]

If time is the measure of movement, and God is unmoved, then God cannot be measured temporally—God is eternal or atemporal. Share on X Based upon the conclusions of the 5 ways alone, we know not only the truth that “God is,” we also know that God is the sovereign, immutable, necessary, intelligent, provident, and final and efficient cause (creator) of all things. Furthermore, we know that God is absolutely Good, True, Noble,[37] Esse, and the cause of these in anything that is.[38] Aquinas will go on, using the conclusions arrived at above, to demonstrate that God is Absolutely Simple, Perfect, Good, Infinite, Immanent and Transcendent, Immutable, Eternal, One, etc. These truth statements about God are, for Aquinas, the preambles of the faith which are demonstrated philosophically, and presupposed in Sacred Doctrine.[39]

A couple examples of how Aquinas moves, philosophically, from the five ways to a greater knowledge of what God is not will be helpful. To demonstrate that God is Absolutely Simple, Aquinas famously considers all of the ways in which things are composed, and then demonstrates, based upon the conclusions of the five ways, that God is not composed in these ways. If God is not composed in these ways, then God is absolutely uncomposed—Absolute Simplicity.[40]

To demonstrate that God is Eternal, Aquinas begins with the conclusion of the first way (that which we call God is the first unmoved—immutable—mover). He then notes that time is the measure of movement (a definition found in Aristotle and in many church theologians). If time is the measure of movement, and God is unmoved, then God cannot be measured temporally—God is eternal or atemporal.[41] Note that both of these doctrines are claims about what God is not—God is not in any way composed, and God is not confined in or measurable by time. The other doctrines mentioned above can all be demonstrated in similar manners.

What does Natural Theology do for us?

We now have a brief excursus of Thomistic Natural Theology. However, we might still ask of Aquinas, what does Natural Theology “do” for us?Natural knowledge of God is neither sufficient nor necessary for salvation but it is useful for convincing unbelievers of the preambles to Christian faith. Share on X

For the Christian theologian, it is, as already noted, helpful for the proper articulation of truths about the divine nature and the right interpretation of Scriptures. It is, however, also important for the unbeliever. Now, as we have already noted, Aquinas does not think that it is possible to attain to the Beatific vision through Natural Theology—natural knowledge of God is neither sufficient nor necessary for salvation. However, for Aquinas, based upon his reading of Scriptures and of the Church Fathers, Natural Theology is also useful for convincing unbelievers of the preambles to Christian faith. In other words, it is useful for evangelism.

In the Summa Contra Gentiles, in a passage which is clearly influenced by the introduction to Gregory of Nyssa’s Great Catechism, Aquinas notes that “the Mohammedans and the pagans accept neither the one [the Old Testament] nor the other [the New Testament]. We must, therefore, have recourse to the natural reason, to which all men are forced to give their assent.”[42]

Unbelievers might not accept the authority of Christian scriptures, but they must bow, suggests Aquinas, to truths which can be known about God from our reasoned observations of the Cosmos.

Endnotes

[1]Cf. discussion of Varro’s distinction between the types of theology, including Natural Theology, in The City of God Against the Pagans, bk. 6, ch. 5; bk. 8, chs. 1-13.

[2]Augustine discusses the many truths known by the Platonists about God in City of God, bk. 8, ch. 6.

[3]Thomas Joseph White, Wisdom in the Face of Modernity: A Study in Thomistic Natural Theology (Ave Maria, FL: Sapientia Press, 2009).

[4]Thomas Aquinas, Faith, Reason and Theology: Questions I-IV of his Commentary on the De Trinitate of Boethius, trans. Armand Maurer (Toronto, ON: PIMS, 1987), 49.

[5]Thomas Aquinas, God, bk. 1 of Summa Contra Gentiles, trans. Anton C. Pegis (1975; repr., Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2005), 63. For future references to the SCG, all quotations will be from Pegis’ excellent translation, and references will follow the traditional form of SCG, 1.3.2, to indicate book, chapter, and section.

[6]Cf. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I, q. 2, a. 2, ad 1. Bauerschmidt, ESTRC, 23fn25. Brian Davies, Aquinas (London/New York: Continuum, 2002), 31-33. Francis J. Beckwith discusses this in his recent work Never Doubt Thomas: The Catholic AQUINAS as Evangelical and Protestant (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2019), 24ff. He rightly points to a number of contemporary Protestant scholars who misunderstood (or perhaps, poorly expressed) this aspect of Aquinas. Beckwith unfortunately sees this as a problem with “Protestant” interpretations of Aquinas, when this is clearly not the case, and a closer reading of 16th and 17th century Protestants would provide him with a different perspective on the Protestant understanding of Aquinas.

[7]For more on the meaning of “natural” in “natural knowledge,” see my paper, “Biblical Interpretation and Natural Knowledge: A Key to Solving the Protestant Problem” in Joseph Minich, ed., Reforming the Catholic Tradition: The Whole Word for the Whole Church (Leesburg, VA: Davenant Press, 2019), 99-134.

[8]All quotes and paraphrases of Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae are my own translations of the Latin text found in the Somme Théologique published by Éditions de la Revue des Jeunes. The Latin text in these volumes is taken from the same sources as the Leonine edition, but was edited (comparing it with multiple editions), by multiple French Thomists, including M.S. Gillet, P. G. Théry, and others. Cf. Thomas d’Aquin, Dieu, tome premier de la Somme Théologique (Latin/Français), trad. A. D. Sertillanges (1947 ; repr., Paris : Éditions de la Revue des Jeunes, Desclée et cie, 1925).

[9]Cf. Aquinas, SCG, 1.4.6-7.

[10]Cf. Aquinas, SCG, 1.4.3. In the SCG, Aquinas gives 3 reasons why this is the case.

[11]It is worth pointing out, here, that though Aquinas does not think there is an “innate idea of God,” or an “implanted notion of God”, he would not rule out what Cicero (and later John Calvin) would call the Sense of the Divine. The difference is that, for Aquinas, this “pre-philosophical notion of God” is more of a desire for goodness which is ultimately God (ST I, q. 2, a. 1, ad 1.). James F. Anderson provides a helpful discussion of the pre-philosophical knowledge of God, when he explains, first, that “a certain pre-philosophical knowledge of God is the indispensable matter out of which some formally philosophical knowledge of Him may be developed.” See Natural Theology: The Metaphysics of God (Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Co., 1962), 4 (italics in Anderson). What is this “pre-philosophical knowledge of God”? Anderson suggests, helpfully, that “the human intellect is a power made for knowing what is, i.e., for knowing being. But if God is pure Being, then the human intellect is made for knowing God. In that case, knowledge of God would be literally natural to the human intellect (4).” Thus, for example, whenever we know being, or desire goodness, or appreciate beauty we are implicitly (unconsciously) knowing something of God, desire God, and loving God. It is, however, a vague or imprecise knowledge of God, as we are not aware that it is God that we are desiring in that pre-philosophical knowledge, desire, and love of divinity. Cf. Aquinas, SCG, 1.11.6. Davies, Aquinas, 35-36. Anderson, NTMG, 8-11.

[12]Cf. Aquinas, SCG, 1.4.4. Aquinas, here, provides 3 reasons why this is the case.

[13]Note how Aquinas is fully in agreement with Augustine here (and both of them with Christian Scriptures), in saying that the philosophers had some knowledge of God.

[14]Cf. Aquinas, SCG, 1.4.5.

[15]For Aquinas, the errors of the philosophers would not count as “knowledge,” but as “false opinions” and an abuse of right reasoning. Cf. Aquinas, SCG, 1.3.4-5.

[16]Furthermore, this means that, for Aquinas, it is impossible for Natural Theology to lead to a salvific knowledge of God. Without divinely inspired Scriptures we would have no knowledge of Christ, without whom there could be no way for man to ascend to union with Christ.

[17]Such as Church leaders.

[18]Cf. Aquinas, SCG, 1.7.1-7. In the SCG, Aquinas notes that this entails that “whatever arguments are brought forward against the doctrines of faith are conclusions incorrectly derived from the first and self-evident principles imbedded in nature. Such conclusions do not have the force of demonstration; they are arguments that are either probably or sophistical. (Aquinas, SCG, 1.7.7.)” Here, it is worth mentioning that Thomas clearly thinks that the particular positions of particular philosophers (and Christian theologians) only hold a “probable” authority in the articulation of Christian doctrine (ST I, q. 1, a. 8, ad 2). Indeed, in this same article, in his response to the 2nd contrary position, Aquinas explains that though human reason is out of its depths in theology, it still plays an important role in the articulation of Christian theology. Human reason cannot demonstrate the truths of revealed scriptures (these are accepted as true, by faith, and then reflected upon), but, it does, says Aquinas, demonstrate other truths which are essential to Christian doctrine (here he is referring to the preambles). Only revealed scriptures hold an absolute authority in Christian doctrine (ST I, q. 1, a. 8, ad 2).

[19]For a helpful discussion of the distinction between demonstrating/knowing “that God is” versus “God’s existence,” see Davies, Aquinas, 39.

[20]For more on whether “God is” is self-evident, see Aquinas, SCG, 1.10-11. For more on whether “God is” is demonstrable, see Aquinas, SCG, 1.12.

[21]Cf. Thomas Aquinas, The Division and Methods of the Sciences: Questions V and VI of his Commentary on the De Trinitate of Boethius, trans. Armand Maurer, 4th ed. (Toronto, ON: PIMS, 1986), 83-4, 92-3. Davies, Aquinas, 36-37.

[22]It is in this article that Aquinas rejects Anselm’s Ontological argument (and, therefore, all similar forms of ontological argument. ST I, q. 2, a. 1, ad 2). James F. Anderson provides a helpful discussion of Aquinas’ rejection of the Ontological argument, discussing the version of it found in Anselm, Descartes, and Leibniz, as well as Kierkegaard’s critique of the Ontological argument (Anderson, NTMG, 13-17.).

[23]Frederick Christian Bauerschmidt provides a similar explanation in his recently published reader and commentary on portions of the Summa Theologiae (The Essential Summa Theologiae: A Reader and Commentary, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2021), 20fn8, 20fn9.).

[24]There is some debate, amongst prominent 20th century Thomists concerning both the validity, and, therefore, utility, of Aquinas’ theistic demonstrations. Fernand Van Steenberghen, for example, is known for having argued both that the 5 ways are insufficient of themselves to demonstrate that God is, and that “none of the 5 ways constitutes, in its literal form, a complete and satisfying proof of the existence of God. The first and second must be made longer, the third and fifth must be corrected and completed, the fourth is useless. See Fernand Van Steenberghen, Dieu Caché (Louvain/Paris: Publications Universitaires de Louvain/Éditions Béatrice-Nauwelaerts, 1966), 187. (My translation from the French.) Anthony Kenny is also known as a major critic, to the least, of the success of the 5 ways. Cf. The Five Ways: St. Thomas Aquinas’ Proofs of God’s Existence (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1969). Though John F. Wippel expresses his doubts about the success of Aquinas’s five way, he does recognize that Aquinas himself seems to think that the proofs were successful. Cf. The Metaphysical Thought of Thomas Aquinas: From Finite Being to Uncreated Being (Washington, D.C.: CUA Press, 2000), 458-59.). Bauerschmidt suggests that for Aquinas, he is talking not about probable arguments, or arguments which would make the intellect tend towards a conclusion, but demonstrations which provide a necessarily true conclusion (Bauerschmidt, ESTRC, 21fn17.). David Oderberg presents a helpful overview of various opinions concerning the success or failure of the 5 ways. Cf. “‘Whatever is Changing is Being Changed by Something Else’: A Reappraisal of Premise One of the First Way”, in Mind, Method, and Morality: Essays in Honour of Anthony Kenny, ed. John Cottingham and Peter Hacker (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 141fn3, 141fn4.

There are, in fact, two important discussions here: (1) considered individually, are the 5 ways successful demonstrations that God is? (2) Should the 5 ways be considered as 5 separate arguments demonstrating that God is, or as 1 argument? One of the helpful conclusions of this discussion is the observation that the 5 ways must be taken as demonstrations that God is, but not anything close to a complete description of the God that is. When Aquinas concludes each of the 5 ways with the statement, “this is what all men call God,” he is not saying “this sums up the totality of the ‘notion’ of deity that men have.” Davies comments on this point are worth quoting here: “Aquinas’s intention in the Ways is minimalist. He is not concerned to show that there is a God who is all that those who believe in him commonly take him to be. Rather, he is out to maintain that God exists under certain limited descriptions” (Aquinas, 39). Also see Brian Davies, The Thought of Thomas Aquinas (1992; repr., Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), 26-27.

[25]See also Aquinas’s discussion of demonstration in questions V and VI of his commentary on Boethius’ De Trinitate (Aquinas, DMS, 24.), and in his Summa Contra Gentiles (Aquinas, SCG, 1.12.6-8.). Cf. Davies, Aquinas, 37. Anderson, NTMG, 21. Gerard Smith, Natural Theology: Metaphysics II (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1951), 55-59.

[26]For example: (i) Socrates is a man; (ii) all men are (by nature) mortal; (iii) Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

[27]Many more examples could be given, as our entire lives are based upon this type of reasoning. We attempt to open a door only to discover that it will not budge, we infer that it is locked and reach for our key. We hear a rattling in our engine, and take the car to the garage (or open the hood), because we infer that the cause of that rattling will require repairs.

[28]For helpful discussions of the principle of causality, which can be traced at least as far back as Plato’s Timaeus (28a), see W. Norris Clark, The One and the Many: A Contemporary Thomistic Metaphysics (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2001); Joseph Owens, An Elementary Christian Metaphysics (1963; repr., Houston, TX: Center for Thomistic Studies, 1985), 75-78. Maurice R. Holloway, An Introduction to Natural Theology (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, inc., 1959), 72-76.

[29]In his commentary on Boethius’ De Trinitate, Aquinas says, “Therefore through natural reason we can know about God only what we grasp of him from the relation his effects bear to him, for example, attributes that designate his causality and his transcendence over his effects, and that deny of him the imperfections of his effects” (Aquinas, FRT, 32). Note, in this quote, the presence of the Triplex Via: the ways of causality, negation, and super-eminence (here “transcendence”). Cf. Aquinas, FRT, 21-22. Aquinas, SCG, 1.3.3.

[30]Aquinas, ST I, q. 2, a. 2.

[31]Aquinas, ST I, q. 2, a. 2, ad 2. Cf. Anderson, NTMG, 21-23.

[32]I here mention the 5 ways that are found in the Summa Theologiae, however, there are other places in his writings we can go to in order to find other proofs. For example, we can also point the interested reader to Aquinas’s demonstration of the existence of God from the observed real distinction of essence and esse in sensible things which leads to the conclusion that there is no real distinction of E/E in God—Essence and Esse, in God, are the same (That is, that God just is Esse.). This argument is found in Aquinas’ short but important treatise De Ente et Essentia: On Being and Essence, trans. Armand Maurer, 2nd ed. (Toronto: PIMS, 1968), 55-57.). Brian Davies notes that a similar form of this argument is also found in De Potentia 7, SCG, 1.22, 2.52, and in ST I, q. 65, a. 1 (Davies, TTTA, 31.). Whether or not Aquinas saw this argument as a theistic proof became one of the major debates in 20th century Thomism, and turned around whether or not it was possible to recognize via natural reasoning alone that there is real distinction of Essence and Esse in creatures, but not in God. Étienne Gilson, famously argued that we come to the knowledge that God’s Essence is His Esse, not from philosophy, but from scriptures—specifically Exodus 3:14. Cf. The Spirit of Mediaeval Philosophy, trans. A. H. C. Downes (1936; repr., Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2009), 51ff.). Here Gilson says, for example, that the very idea that there is no real distinction of E/E in God—that is, that Being “designates the essence of God, and the essence of no other being but God” (51) is a truth which was given to man through special revelation alone, and it thus became the basis of Christian Philosophy (51ff). If this is the case, then either the argument in De Ente et Essentia is not a philosophical demonstration that God is, or it is a demonstration which takes it’s point of departure in Special Revelation. Either way, it could not be a philosophical demonstration that God is. As the E/E distinction is so fundamental to philosophy, this would mean that the most important principles of philosophy are dependent upon special revelation.

Against Gilson, we find M. Gillet, Thomas d’Aquin (Paris, 1949), 67-68.), Fernand Van Steenberghen, “Le problème de l’existence de Dieu dans le ‘De ente et essentia’ de Saint Thomas d’Aquin,’”, in Mélanges Joseph de Ghellinck, II (Louvain, 1951), 837-47.), Joseph Owens (ECM, 80-81, 337-38.), Brian Davies (TTTA, 31-33.). Edward Feser appears to present a version of the argument of the De Ente et Essentia as a theistic proof (Five Proofs of the Existence of God (San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2017), 117-45.). There were many more Thomists involved in this intriguing debate. Thomas Joseph White conclusively shows the errors of Gilson’s approach in his Wisdom in the Face of Modernity, 116-32. By making philosophy depend upon special revelation for its primary principle, Gilson ends up falling into the same problem that he argued against in his Unity of Philosophical Experience. For an excellent recent overview of the entire debate, and evidence that the argument of the De Ente et Essentia is indeed intended to be a demonstration that God is, see Gaven Kerr, Aquinas’s Way to God: The Proof in De Ente et Essentia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015). Recent research on the thought of Aquinas has demonstrated conclusively that, for Aquinas, the proper interpretation of Exodus 3:14 is supported by the naturally known truth that there is no real E/E distinction in God (that the divine essence is esse), philosophy is not dependent upon Exodus 3:14 for knowing that there is no real E/E distinction in God. Exodus 3:14 is not assumed in order to know this truth, but, is rightly understood in light of this truth. This point is important for properly understanding Aquinas. He clearly thinks that it is possible to know, by the natural light of reason alone, the truth of the proposition “God is.” The natural light of reason is not dependent upon special revelation for any one of the premises included in the demonstrations of the truth that “God is.”

See, also, the proofs found in his Summa Contra Gentiles, book 1, ch. 13, which resemble the 5 ways (though not all 5 ways are found here), but which are worked out in much more detail. Anderson also outlines a number of other possible demonstrations that God is (Anderson, NTMG, 55-60.), including arguments based upon human reasoning, Art and the practical intellect, and morality.

[33]Aquinas is not saying, here, that God is the “Most Perfect Being” as in the highest in some measurable category, but, rather, in a more Plotinian manner, that God is Pure Esse—the pure act of be-ing unmixed with any becoming or non-being. God is not at the top of a hierarchy of Being, of which he happens to be greatest or highest. God is entirely distinct; the hierarchy receives it’s being from God. This is what the doctrine of the analogia entis is getting at. God is so entirely other, that when we predicate “being” of God, we must do so neither equivocally (in which the predicate means something entirely different), nor univocally (in which the predicate means precisely the same thing), but analogically (for, though there is something of created “being,” “goodness,” etc., which resembles, in some way, divine “being” and “goodness,” it is also true to say that created being and goodness is so little like divine being and goodness that they are almost incomparable. Similar, but distinct—analogical predication.). Cf. Anderson, NTMG, 47.

[34]The value of the fourth way has been questioned by some (such as Van Steenberghen, Dieu Caché, 187.), but is defended as helpful by others (cf. Davies, Aquinas, 51.).

[35]John F. Wippel, “Thomas Aquinas on our Knowledge of God and the Axiom that Every Agent Produces Something Like Itself”, in John F. Wippel, Metaphysical Themes in Thomas Aquinas II (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2007), 152.

[36]Cf. Aquinas, SCG, 1.29-36. Wippel, “Thomas Aquinas on our Knowledge of God and the Axiom that Every Agent Produces Something Like Itself”, 153.

[37]Which some have taken to refer to Perfection or Excellence (Wippel, MTTA, 471-72.).

[38]It is not due to creaturely goodness, beauty, truth, or being, that God is Good, Beautiful, True, and Being, but, the inverse. Though we come to know that these rightly attributed analogically to God because we observe them in creatures, they are in creatures because they are first and absolutely in God. We distinguish, here, between ontological priority and the order of learning or knowledge for humans.

[39]John Wippel provides a very helpful analysis of Aquinas’s claims about what can be naturally known of God and what must be counted as an article of faith in his article “Thomas Aquinas on Demonstrating God’s Omnipotence,” in John F. Wippel, Metaphysical Themes in Thomas Aquinas II, 194-217.

[40]Cf. Aquinas, SCG, 1.18-27. Aquinas, ST I, q. 3.

[41]Cf. Aquinas, SCG, 1.15.1-3. Aquinas, ST I, q. 10, aa. 1-2.

[42]Aquinas, SCG, 1.2.3.