Karl Barth once wrote: “Fear of scholasticism is the mark of a false prophet” (CD I/1, 279). I highlighted that sentence many years ago when I was reading Barth with far more sympathy than I do today. It made me hopeful that Barth was serious about recovering historic Christian Trinitarian and Christological orthodoxy after the disastrous nineteenth century of Protestant culture religion. Early in his career Barth did study the Reformed confessions and the Protestant scholastics diligently in search of alternatives to the failed liberalism of Harnack and Ritschl. He did find real theological substance in the post-Reformation theologians, and he engaged it vigorously. Barth was not afraid of post-Reformation, Protestant scholasticism.

Barth’s Rejection of the Scholastic Doctrine of Election

B ut while he engaged scholasticism, he never really accepted the substance of its doctrine at many key points. He was particularly critical of the reformed doctrine of election. While not rejecting the doctrine altogether, he sought to reform and rework it in radical ways. He attempted to reform it Christologically by making Jesus Christ both the electing God and the elect man. He saw the mystery of Divine election in the traditional formulation as a cloak for a “hidden God” behind the God revealed in Jesus Christ and so he rationalized away the mystery in a way that appeared to many to lead to universalism. He accomplished this by moving the decree from the inscrutable will of God, which is inaccessible to human beings, to the history of God’s action in Jesus Christ, which is revealed and thus accessible in Holy Scripture. Thus, he historicized the decree and made it comprehensible on the basis of special revelation. But the price he paid was that he historicized God himself as well because, on his account, God elects himself to be the Son and so the Trinity itself is the result of God’s decree. This interpretation of Barth is controversial and interpreters such as George Hunsinger and Paul Molnar might disagree. But it is follows Bruce McCormack’s interpretation, which I fear is accurate.For scholastic theology, God is the First Cause or primary cause of all that exists, but he is not the efficient cause of every act of creatures. Share on X

ut while he engaged scholasticism, he never really accepted the substance of its doctrine at many key points. He was particularly critical of the reformed doctrine of election. While not rejecting the doctrine altogether, he sought to reform and rework it in radical ways. He attempted to reform it Christologically by making Jesus Christ both the electing God and the elect man. He saw the mystery of Divine election in the traditional formulation as a cloak for a “hidden God” behind the God revealed in Jesus Christ and so he rationalized away the mystery in a way that appeared to many to lead to universalism. He accomplished this by moving the decree from the inscrutable will of God, which is inaccessible to human beings, to the history of God’s action in Jesus Christ, which is revealed and thus accessible in Holy Scripture. Thus, he historicized the decree and made it comprehensible on the basis of special revelation. But the price he paid was that he historicized God himself as well because, on his account, God elects himself to be the Son and so the Trinity itself is the result of God’s decree. This interpretation of Barth is controversial and interpreters such as George Hunsinger and Paul Molnar might disagree. But it is follows Bruce McCormack’s interpretation, which I fear is accurate.For scholastic theology, God is the First Cause or primary cause of all that exists, but he is not the efficient cause of every act of creatures. Share on X

Why did Barth reject the scholastic doctrine of election? I think a big part of the reason is that, although he did engage with Protestant scholastic theology, he never felt it was possible to take on board its metaphysical framework. In this case, the key distinction between the simple, immutable, eternal God and the complex, changing, temporal creation results in a difference in the type of causality exercised by God on the creation. For scholastic theology, God is the First Cause or primary cause of all that exists, but he is not the efficient cause of every act of creatures. The difference between primary and secondary causality is fundamental to the scholastic analysis of the doctrine of election. God creates the creature and the creature sins, but God does not cause the sin, only the creature. God imparts regenerating grace, and the regenerated sinner is enabled to repent and believe the gospel. God is the primary cause of all but he operates through the secondary causation of creatures.

In the Enlightenment, however, the analysis of causation was grossly over-simplified, and reduced to only efficient and material causation. Formal and final causation was ignored. The natural science of physics seems to work well without appeal to formal or final cause, so it was assumed that all sciences, including theology, should be able to work equally well using only efficient and material causation. This reductionistic scientism affected all science, philosophy, and theology during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and culminated in Hume’s denial of the principle of causality in the late eighteenth century. Kant assumed that Hume’s rejection of classical metaphysics and its traditional analysis of causation was right and so he devised his critical philosophy to provide some sort of basis for natural science in the light of the new metaphysical situation. Kant denied that we can know things in themselves; all we can know is the objects of sense perception as organized by the categories of the understanding. The degree to which these categories of the understanding accurately reflect mind-independent reality would become a key debate over the next two centuries, which continues today. In the early twenty-first century, a near-total skepticism has triumphed in the form of what is usually called “postmodernism,” but which I would call the decadent, late phase of modernity.

The key to understanding Barth’s theology is to see that he never really managed to break free of the Kantian rejection of classical metaphysics. He attempted to bring the dogmatic substance of classical orthodoxy into the modern world of historicism. It was a sincere effort to be, as Bruce McCormack put it, to be both “orthodox and modern.” He refused to reject Schleiermacher completely because he knew that the only way to do so would require finding a way to circumvent Kant’s prohibition on knowing the essence of a “thing in itself.” So, Barth did not challenge the fundamental shift in modern theology from a focus on the being of God to a focus on human experience of God. Barth’s famous Christocentric approach only appears to avoid modern anthropocentrism.

Barth saw Schleiermacher’s feeling of dependence on God as a way of knowing God in the post-Kantian situation, but Barth believed that it was too abstract and too general to serve as the basis for church dogmatics. So, instead of the feeling of absolute dependence, Barth substituted the knowledge of Jesus Christ as the incarnate Lord in its place. All dogma would thus be derived from Christology. For this reason, his Church Dogmatics begins with the doctrine of the Trinity in volume one instead of the traditional proofs for the existence of God.

The problem was not that he made Christology central to theology; rather, it was that his Christology was historicized. Barth never challenged the central dogma of nineteenth century liberal Protestantism, which is that “history” is the realm of the natural only and that the supernatural is beyond and outside of history. History consists of only that which can be accessed empirically. This is what I mean by “historicism.” From Hegel onwards this historicism dominated Protestant theology and was the foundation of the historical critical method of biblical interpretation. The relationship between history and revelation in Barth’s thought is complex and possibly, in the end, incoherent.As the primary (or first) cause of all that is, God does not operate on the same causal plane as creatures. Share on X

Since Barth believed that Kant’s rejection of classical metaphysics was irreversible, he accepted that any theology that wished to be modern must work within the parameters of historicism. So, he reworked Christology on the basis of human consciousness operating within the parameters of a historicism, which was actually a disguised philosophical naturalism. Schleiermacher grounded Christ’s divinity in his God-consciousness and Barth ended up doing something similar in his narrative Christology, as Thomas Joseph White shows in his book: The Incarnate Lord: A Study in Thomistic Christology.

At no point is Barth’s submission to Kantianism more obvious than in his rejection of the analogia entis as the invention of the antichrist. He could not accept that the Thomistic proof of God’s existence was valid, and he supposed (correctly) that it was the basis of the analogia entis. Yet, he did not realize that the validity of the analogia entis is the only reason why we can speak of Divine causality in such a way that God is conceived as more than simply a cause within the created order, but, in fact, as a transcendent Creator whose action with regard to creation is understood analogically by reference to intra-creation causality. As the primary (or first) cause of all that is, God does not operate on the same causal plane as creatures. The relationship between the two kinds of causation is analogical. As Thomas Joseph White demonstrates so beautifully, if Barth could have accepted the analogia entis he would have been able to achieve his goal of preserving the transcendence and utter uniqueness of God without cutting God off from the world. And he could have had the Thomistic proof for God’s existence and the classical metaphysics that flowed from it instead of deferring to Kantian skepticism. Having at his disposal an account of primary and secondary causation, understood analogically, could have allowed him to adopt and refine, rather than reject and replace, the scholastic doctrine of election.

What Can We Learn from this History?

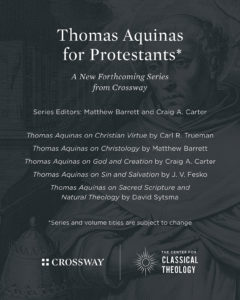

We should summarily reject nineteenth century historicism and the flawed metaphysical assumptions on which it rests. Thomas Joseph White and many others in the Thomistic Ressourcement movement (such as Gilles Emery, Matthew Levering, and Dominic Legge) are providing the impetus for doing this and confessional Protestants need to learn from them. White, for example, is far more radical in his rejection of modernity in general, and of Kant in particular, than Barth ever was. Today, a century after Barth, it is now clear that the supposed revival of Trinitarian theology inspired by Barth has fizzled out and it is now apparent that Barth’s attempt to restate orthodoxy within the constraints of Kantianism has failed. Therefore, the time has come to re-visit scholasticism. The rediscovery of the value of the metaphysics of Thomas Aquinas does not necessarily lead back to Roman Catholic theology. Thomas can just as well lead us back to the post-Reformation, Protestant scholasticism. Historians of the post-Reformation period such as Heiko Oberman, David Steinmetz and Richard Muller make this clear.

Who is afraid of scholasticism? Nobody should be afraid of it. John Webster, in his contribution to a volume entitled: The Analogy of Being: Invention of the Antichrist or the Wisdom of God, scoffed:

“Is the analogy of being the invention of the Antichrist? Hardly, it is a theologoumenon, no less and no more; surely the Antichrist would unleash something a bit more destructive than a somewhat recherche bit of Christian teaching?” (394)

This book was published in 2011. There is reason to think Webster’s opinion of the analogia entis went up not down in the last few years of his life. In any case, the fact is that Webster was highly involved in the study of the same Protestant scholasticism at the end of his career that Barth had been involved in studying at the beginning of his career. Their trajectories were in opposite directions and there are reasons to believe that Webster’s embrace of Protestant scholasticism included the metaphysics woven into its fabric.

Webster’s embrace of Thomistic thought in the final decade of his life showed little of the anxiety displayed by so many about being labeled “anti-modern” or “irrelevant.” For Webster, modernity was not to be absolutized any more than any other historical period or methodology. For him, as for all the great theologians of history, the substance of dogmatics takes priority over methods or fads. As he once put it to me personally on more than one occasion, “Let the doctrines do the work,” by which he meant engage the substance of the dogma and let that reform your methodology as you go along. A more anti-modern piece of advice could scarcely be imagined.I am convinced that we need to recover and revitalize scholastic realism if we are to recover and revitalize classical orthodoxy after the disasters of the last two centuries. Share on X

I am convinced that we need to recover and revitalize scholastic realism if we are to recover and revitalize classical orthodoxy after the disasters of the last two centuries. The nineteenth and twentieth centuries are among the most forgettable in the two-millennium history of Christian theology. If we are going to bring the Trinitarian orthodoxy of Nicaea and the Christological orthodoxy of Chalcedon to the forefront of Christian dogmatics again, which is the most important task facing theology in the twenty-first century, then we are going to need to reach behind the Hume-Kant-Hegel watershed of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. We are going to need to go back to the last period in history when Enlightenment rationalism and naturalism had not yet corrupted Christian theology. And that period is the period of post-Reformation scholasticism.

One of the strengths of this period of Protestant scholasticism is its catholicity, that is, its deep roots in the best of medieval scholasticism and the early church fathers. The Protestant reformers were highly suspicious of late medieval voluntarism and nominalism and much of their anti-scholastic rhetoric should be understood as directed against those targets. Many of the best Protestant theologians found that the theology of Thomas Aquinas had deep roots in both Greek and Latin patristic writers and was an exposition of the trinitarian and Christological dogmas symbolized in the great ecumenical creeds. So, they employed it extensively and with profit.

In the book, Without Excuse: Scripture, Reason, and Presuppositional Apologetics, edited by David Haines, we have a collection of essays of uneven quality seeking to raise important questions for the presuppositionalism of Cornelius Van Til and his followers. The debate it opens is a necessary one, for in many ways Van Til exhibited a fear of scholasticism that surpassed that of Barth. Two essays in this book explore topics of particular relevance to this discussion: Manfred Svensson’s “The Use of Aristotle in Early Protestant Theology” and David Haines’s “The Use of Aquinas in Early Protestant Theology.” Both show that the early reformers made extensive use of the metaphysical assumptions woven into the fabric of trinitarian and Christological orthodoxy inherited by the sixteenth century. Indeed, one could well ask: “How could it have been otherwise?” The Reformation was not about rejecting the Nicene doctrine of the Trinity and Chalcedonian Christology. It was about reforming the doctrines of soteriology and ecclesiology through a recovery of the authority and perspicuity of Holy Scripture.Who is afraid of scholasticism? Not Reformed Thomists. Share on X

Haines concludes that reformers like Zanchi, Beza, Vermigli, and Bullinger “followed Aquinas so closely that they might even be called “Reformed Thomists.” (233) Although Haines is working from primary sources in this essay, his conclusion is consistent with the best historiography of our day (e.g. Richard Muller). It seems to me that here we find the sources of the classical expressions of the Reformed faith that would emerge over the next two centuries, including the Westminster standards. Here we find the metaphysical and dogmatic foundations of Reformed scholasticism, or as one could also put it, classic reformed theology. The roots are in Reformed Thomism. It is an amazing and wonderful thing to see the rediscovery and retrieval of these roots of the reformed faith in the twenty-first century. Who is afraid of scholasticism? Not Reformed Thomists.